The SOLERA PROCESS

Ivan VLADISLAVIC;

in conversation with Dominic JAECKLE;

on and around VLADISLAVIC’s novel

The Distance

(Archipelago Books, 2020)

In his youth in 1970s suburban Pretoria, during a pivotal decade in South African history amid growing resistance to apartheid, Joe falls in love with Muhammad Ali. Diligently scrapbooking newspaper clippings of his hero, Joe records and imbibes the showman’s inimitable brand of resistance. Forty years later, digging out his yellowed archive of Ali clippings and comics, Joe sets out to write a memoir of his childhood. Calling upon his brother Branko for help, their two voices interweave to unearth a shared past, and a new perspective on the realities of growing up with a conservative father in a segregated society. Reconstructing a world of bioscopes, Formica tabletops, Ovaltine, and drop-offs in their father’s Ford Zephyr, conjuring the textures of childhood, what emerges is a collision of memories, patching the gulf between past and present. Meaning arises in the gaps between fact and imagination, and words themselves become markers of the past, charting an era of racism into the turbulent present. In this formally inventive, fragmented novel, Vladislavic evokes the beauty, and the strangeness, of remembering and forgetting, exploring the various forms of violence and rebellion, and what it means to be at odds with one’s surroundings. The Distance can be ordered direct from the publisher here.

Hotel ran an exclusive excerpt from the novel; see here. Vladislavic and Jaeckle exchanged a run of emails as October dipped into November; see below for the conversation in full.

Hotel ran an exclusive excerpt from the novel; see here. Vladislavic and Jaeckle exchanged a run of emails as October dipped into November; see below for the conversation in full.

I. THE PISTOL IN EPISTOLARY

(or CORRESPONDENCE AS A KIND OF CONFLICT)

D.J. — I’d like to begin with this famous passage from Joyce Carol Oates’ evergreen exploration of the art of boxing and the act of reading;

A certain kind of a harmony can be struck between Oates’ sense of boxing as a pertinent metaphor for the varied rounds of a life, the ‘again the bell’ of popular experience, and The Distance—the work we have here at hand. Her want to explore the universalism and vivacity inherent to the sport as akin to the gamified (and reified) violence of daily life is mirrored in the correspondence of Joe and Branko, whose letters provide a means of detailing how passion, interest and enthusiasm underwrite a want to read ‘boxing as a symbol of something beyond itself’ and a desire to speak beyond the ‘something itself’ of quotidian living. But it’s also Oates’ allusion to the ring, to the ‘elevated platform enclosed by ropes’ beneath ‘pitiless lights,’ that I’d like to lead with in this discussion.

An easy starting gate for our conversation is to consider the novel itself (formally speaking) as our ‘elevated platform,’ as our stage or arena. The ‘impatient’ god-light of our attention span serves as something akin to the ‘hot and crude’ bulbs above and around the ring as we read a narrative subdivided into rounds; into a sequence of monologic letters that serve variously as dissections of family, of being, of place, of passion that run as discrete punches or swings across these pages. Ali may be the pin upon which these ideas sing and depend, but the narrative itself mirrors the game that sits at the novel’s heart. The bout of back-and-forth letters between these two brothers that gives this novel its shape feels itself like a form of sporting conflict, and I was curious as to whether you could perhaps speak to your initial decision to write this book as a jilted competition of voice?

There are a few further stylistic questions as well… The absence of speech marks, for instance; the absence of direct address; the possessive character of personal narrative; the possessive adoration of Ali. All these intersecting elements in the novel’s call and response structure feel like the ground floor of an effort to contest and explore the possibility that boxing could serve ‘as a symbol of something beyond itself,’ but that the letter sits as your chosen form for this probing novel of self-search is of interest…

![]()

![]()

I.V. — I’m tempted to start with rugby. That’s not as contrary as it sounds. Although it’s a team sport played with a ball, rugby bears comparison with boxing in the way it combines force, grace and skill. Also, while it is not South Africa’s national sport, on a few memorable occasions rugby has become the vehicle for expressing visions of who we are as a country, or who we would like to be. This is the sporting contest as allegory, rather than metaphor, a staging of conflict in which the demons of the fans are exorcised and the tenets of their faith renewed, to paraphrase Eduardo Galeano, who writes so passionately about soccer. I suppose that boxing often provides fans with an allegorical stage. In Budd Schulberg’s slightly lurid formulation (quoted by one of my characters) boxing matches are ‘allegories authored in blood.’

What is boxing doing in my novel? I like your formal analogy in which the novel itself is a ‘ring’ and the dual narrative a ‘bout’. Boxing offers a set of rules, moves, rhythms that structure proceedings. Fifteen rounds, fifteen chapters. Why not twelve? Professional bouts may be fought over twelve rounds rather than fifteen. Because twelve is an unsatisfactory number, according to my own personal rules of the writing game, and would not allow for a symmetrical arrangement of chapters turning on a central point (Chapter 8). This tells me that the boxing materials may be subordinate to or shaped by other demands of imagination and craft.

When I began writing The Distance, I had a single narrator, a forebear of the character Joe, who was trying to accomplish two things: firstly, to make sense of the cuttings in a set of scrapbooks about the career of Muhammad Ali, in a pseudo-analytical way, almost as if he were a cultural anthropologist; and secondly, to recall and recount aspects of his boyhood, in the same period when the cuttings were assembled, in a lyrical mode, almost as if he were a memoirist. The two tasks, with their different registers and focal points, were impossible to reconcile. At some point I acknowledged that I had two characters rather than one, and so I gave Joe a brother, with whom he could share the load.

Like many brotherly relationships this one proved to be argumentative. Joe and Branko are opponents of the sort who batter and bruise one another, and then embrace at the end. They are indeed engaged in a battle, an exchange of written blows. Initially, I had the idea of structuring the novel so that Joe and Branko were always on opposing pages, verso and recto, confronting one another across the spine of the book. This blow-by-blow arrangement, this call and response, in your gentler phrasing, seemed too mechanical and constraining. For the writer, but also for the imagined reader, required to read two texts side by side. The effect might have been something like those Penguin Parallel Texts, where a story appears on the left-hand page in its original version, say German or French, and on the right in the English translation. Once I relinquished this shadow-boxing structure, the characters came into their own, and the text became looser and more improvisatory, although the outlines of the fifteen-round contest still shine through.

Your perception that the sections are ‘letters’ is intriguing. The narrators are clearly engaged in an exchange of accounts, notes, entries, whatever one could call them, but it never occurred to me that they were letters. I’ve been looking at the novel afresh in this light. Although it’s unusual for a letter to avoid addressing the recipient—I don’t think there’s a second-person address outside the dialogue—I see that it might be taken this way. I’ve always wanted to write an epistolary novel, and the idea that I may have written one inadvertently is encouraging.

[I can’t] think of boxing in writerly terms as a metaphor for something else. No one whose interest began as mine did—as an offshoot of my father’s interest—is likely to think of boxing as a symbol of something beyond itself, as if its uniqueness were merely an abbreviation, or iconographic; though I can entertain the proposition that life is a metaphor for boxing—for one of those bouts that go on and on, round following round, jabs, missed punches, clinches, nothing determined, again the bell and again and you and your opponent so evenly matched it’s impossible not to see that your opponent is you: and why this struggle on an elevated platform enclosed by ropes as in a pen beneath hot and crude pitiless lights in the presence of an impatient crowd?—that sort of hellish-writerly metaphor. Life is like boxing in many unsettling respects. But boxing is only like boxing.

Joyce Carol Oates, On Boxing (2006)

A certain kind of a harmony can be struck between Oates’ sense of boxing as a pertinent metaphor for the varied rounds of a life, the ‘again the bell’ of popular experience, and The Distance—the work we have here at hand. Her want to explore the universalism and vivacity inherent to the sport as akin to the gamified (and reified) violence of daily life is mirrored in the correspondence of Joe and Branko, whose letters provide a means of detailing how passion, interest and enthusiasm underwrite a want to read ‘boxing as a symbol of something beyond itself’ and a desire to speak beyond the ‘something itself’ of quotidian living. But it’s also Oates’ allusion to the ring, to the ‘elevated platform enclosed by ropes’ beneath ‘pitiless lights,’ that I’d like to lead with in this discussion.

An easy starting gate for our conversation is to consider the novel itself (formally speaking) as our ‘elevated platform,’ as our stage or arena. The ‘impatient’ god-light of our attention span serves as something akin to the ‘hot and crude’ bulbs above and around the ring as we read a narrative subdivided into rounds; into a sequence of monologic letters that serve variously as dissections of family, of being, of place, of passion that run as discrete punches or swings across these pages. Ali may be the pin upon which these ideas sing and depend, but the narrative itself mirrors the game that sits at the novel’s heart. The bout of back-and-forth letters between these two brothers that gives this novel its shape feels itself like a form of sporting conflict, and I was curious as to whether you could perhaps speak to your initial decision to write this book as a jilted competition of voice?

There are a few further stylistic questions as well… The absence of speech marks, for instance; the absence of direct address; the possessive character of personal narrative; the possessive adoration of Ali. All these intersecting elements in the novel’s call and response structure feel like the ground floor of an effort to contest and explore the possibility that boxing could serve ‘as a symbol of something beyond itself,’ but that the letter sits as your chosen form for this probing novel of self-search is of interest…

I.V. — I’m tempted to start with rugby. That’s not as contrary as it sounds. Although it’s a team sport played with a ball, rugby bears comparison with boxing in the way it combines force, grace and skill. Also, while it is not South Africa’s national sport, on a few memorable occasions rugby has become the vehicle for expressing visions of who we are as a country, or who we would like to be. This is the sporting contest as allegory, rather than metaphor, a staging of conflict in which the demons of the fans are exorcised and the tenets of their faith renewed, to paraphrase Eduardo Galeano, who writes so passionately about soccer. I suppose that boxing often provides fans with an allegorical stage. In Budd Schulberg’s slightly lurid formulation (quoted by one of my characters) boxing matches are ‘allegories authored in blood.’

What is boxing doing in my novel? I like your formal analogy in which the novel itself is a ‘ring’ and the dual narrative a ‘bout’. Boxing offers a set of rules, moves, rhythms that structure proceedings. Fifteen rounds, fifteen chapters. Why not twelve? Professional bouts may be fought over twelve rounds rather than fifteen. Because twelve is an unsatisfactory number, according to my own personal rules of the writing game, and would not allow for a symmetrical arrangement of chapters turning on a central point (Chapter 8). This tells me that the boxing materials may be subordinate to or shaped by other demands of imagination and craft.

When I began writing The Distance, I had a single narrator, a forebear of the character Joe, who was trying to accomplish two things: firstly, to make sense of the cuttings in a set of scrapbooks about the career of Muhammad Ali, in a pseudo-analytical way, almost as if he were a cultural anthropologist; and secondly, to recall and recount aspects of his boyhood, in the same period when the cuttings were assembled, in a lyrical mode, almost as if he were a memoirist. The two tasks, with their different registers and focal points, were impossible to reconcile. At some point I acknowledged that I had two characters rather than one, and so I gave Joe a brother, with whom he could share the load.

Like many brotherly relationships this one proved to be argumentative. Joe and Branko are opponents of the sort who batter and bruise one another, and then embrace at the end. They are indeed engaged in a battle, an exchange of written blows. Initially, I had the idea of structuring the novel so that Joe and Branko were always on opposing pages, verso and recto, confronting one another across the spine of the book. This blow-by-blow arrangement, this call and response, in your gentler phrasing, seemed too mechanical and constraining. For the writer, but also for the imagined reader, required to read two texts side by side. The effect might have been something like those Penguin Parallel Texts, where a story appears on the left-hand page in its original version, say German or French, and on the right in the English translation. Once I relinquished this shadow-boxing structure, the characters came into their own, and the text became looser and more improvisatory, although the outlines of the fifteen-round contest still shine through.

Your perception that the sections are ‘letters’ is intriguing. The narrators are clearly engaged in an exchange of accounts, notes, entries, whatever one could call them, but it never occurred to me that they were letters. I’ve been looking at the novel afresh in this light. Although it’s unusual for a letter to avoid addressing the recipient—I don’t think there’s a second-person address outside the dialogue—I see that it might be taken this way. I’ve always wanted to write an epistolary novel, and the idea that I may have written one inadvertently is encouraging.

II. THE ARC OF AN ARCHIVE

(or SECOND-HAND IDEAS AS A FIRST GAME BELL)

You realize you can’t be Rocky Marciano, you can’t be Jake LaMotta, but you could take pieces of them and try to make your own way.

Ray ‘Boom-Boom’ Mancini in interview

Without the boxing writers, my love for Muhammad Ali would not have bloomed. You could say I fell in love with the writing rather than the boxing. After all, I never saw Ali box. Everything I knew about him came down the wire; it was all second hand, on the page.

Ivan Vladislavic, The Distance (2020)

D.J. — The fourth Chapter in The Distance, ‘Americans,’ begins with a nod to a knitting machine in an epigraph lifted from a 1972 newspaper:

Knitting machines. Many well-known makes. Demonstration models as new. Guaranteed perfect condition. Very low price. Free lessons. Terms arranged. Knitter’s friend, 25 Harvard Building.

(Cor. Joubert and Pritchard Street) JHB.

And, in the novel’s opening pages, Joe revels in his early impulses as an amateur archivist, and signals the importance of the Ali/Frazier ‘Fight of the Century’ (8th March, 1971) to his burgeoning self-awareness:

We had no television in South Africa then, and our news came from the radio and the newspapers. The Fight of the Century produced an avalanche of coverage in the press. My Dad read the daily Pretoria News and two weeklies, The Sunday Times and the Sunday Express, and so these were my main sources of information. In the buildup to the fight I started to collect cuttings and for the next five years I kept everything about Ali that I could lay my hands on, trimming hundreds of articles out of the broadsheets and pasting them into scrapbooks. Forty years later, these books are spread out on a trestle table beside my desk as I’m writing this. Let me confess: I’m writing this because the scrapbooks exist.

The heart of my archive is three Eclipse drawing books with tracing-paper sheets between the leaves. These books have buff cardboard covers printed with Eclipse trademarks and the obligatory bilingual ‘drawing book’ and ‘tekenboek.’ In the middle of each cover is a hand-drawn title: ALI I, ALI II and Ali III. The newsprint is tobacco-leaf brown and crackly. When I rub it between my fingers, I fancy that the boy who first read these reports and I are one and the same person.

The scrapbooks are, perhaps, the most constant of characters across the novel and—at the backend of the book—we’ve a note that remarks upon your own amassing of Joe’s archive and a dedication to the sportswriters, ‘local and syndicated,’ of the Pretoria News, The Star, the Sunday Times and Express, et al. ‘This novel draws on a collection of newspaper and magazine cuttings from 1971 to 1975,’ to borrow your own wording. Could you remark on your experience of collecting and collating this material? On the decision involved in folding these press notes into these pages? The ‘knitting machine’ also feels like a curious play on both the scrapbooks that feature so heavily in the novel and your process of pulling the work together; could you remark on the mechanical process of scrapbooking and its kinship with your practice?

I.V. — I remember vividly how I collected the cuttings. Once my father and I had finished reading the newspapers, I cut out the articles related to Ali, usually on the coffee table in the lounge. Joe’s fictional descriptions of the process are fairly accurate. The decision to fold the cuttings, so that as many as possible could be fitted onto a single page, was a practical one aimed at extending the life of the drawing books, but I probably enjoyed solving the puzzle of the assembly too.

I’m glad you single out the knitting machine epigraph. The mother in the novel has a knitting machine and also knits and sews by hand. Like these handicrafts, scrapbooking was probably regarded as something women did. There’s the suggestion of a link between the mother’s sewing and Joe’s writing: I’m thinking of the burning of the mother’s dream journal, where Joe describes the charred remains of the book as a ‘bloodied spine trailing a nervous system of cotton thread.’ This is in the chapter called ‘Collectors’ and the scene follows one that describes Joe’s lists of names from the Bible. So the collection of words and stories and the handcrafting of objects have at least an associative connection.

By chance today I came across an interview with the tapestry artist Billie Zangeswa, who is known for her domestic interiors sewn from pieces of silk. Her mother was a dressmaker and she recalls watching her sew when she was a child: ‘I saw my mother sewing, but she never taught me, and I never asked … I’d sit quietly in the corner and watch with fascination’ (BOMB magazine newsletter, 12 October 2020). Zangeswa refers to stitching as a meditation. Visual artists and crafters often speak about the meditative states induced by repetitive work. The inking of repeated phrases and slogans that Joe describes in the novel must have been absorbing in this way. It is rare to experience this as a writer, to get through the conscious grappling with language to the point that it becomes a fluid material.

One of the formal challenges the novel presented was how to incorporate the quotations from the cuttings, bearing in mind that I wanted to preserve their status as borrowed texts. I started out with them in quotation marks, but that produced a bristly sort of surface. Putting them into italics made them stand out too clearly. The solution arrived at in the published text, in which the quotations have a grey screen, strikes a good balance, I think. You tend to lose sight of the screen as you read, but the inserts become clear if you focus. It’s not seamless, in other words. A similar effect was achieved in the South African edition with a lighter variant of the same font.

Before we close the lid of the sewing box—I am reminded of the concept of the ‘seam’, which the literary scholar Leon de Kock employed to describe South Africa’s cobbled-together culture. He argued that we generally proceed by seaming together things that do not really belong, that fit together uncomfortably or provisionally. It’s interesting that he chose a metaphor that suggests pursuits like mending or patching.

If I had to characterize my own method, I would lean towards the notion of collage, or perhaps more accurately, montage, as suggested by the ‘cutting.’ In a scrapbook things are edged together without being joined. They might fall apart or scatter as Joe’s scrapbooks do in the novel. I could say more about this, perhaps in relation to Jordan’s film Overkill: A speculative documentary about death. But let me stop for now and hear from you.

III. THE SOLERA PROCESS:

HEMING & HAWING THROUGH

SEMES

& SEAMS

(or ELIZABETH COSTELLO GOES TO THE MOVIES)

[Joe] goes to the lounge and then I hear him cursing and banging. The fucking fire’s gone out. He drags one of the broken leather armchairs closer to the fire and makes me sit, pours me a shot of sherry and starts telling me all about the solera process, how they tap the sherry from one barrel to another, high to low. It’s like a metaphor, he says, for how culture works.

Ivan Vladislavic, The Distance (2020)

D.J. — The accidental or inadvertent epistolary is definitely an interesting thing, and something I’d like to keep in mind as we talk on; the idea of this book as a broken correspondence came to mind partly in response to Joe’s assertion—about midway through the novel—that ‘boxing [is] a kind of physical wit,’ ‘verbal wit a kind of sparring.’ It continuously feels as though both characters are writing missives to those ideas, rather than to one another.

That we get a different kind of cultural epistolary off the back of that is a fascinating characteristic of The Distance and, to think that through a little further (and ahead of our coming to Jordan’s ‘speculative’ documentary), I’d love to leave the sewing box open for a second longer and consider the ‘seam’ in a little more detail. De Kock admits that the ‘seam’ is a term he borrows from Noël Mostert who, in Frontiers (1992), supposes that ‘if there is a hemispheric seam to the world, between Occident and Orient, then it must lie along the eastern seaboard of Africa.’ To quote De Kock on Mostert, ‘nowhere does one find such a confluence of human venture and its many frontiers, across time, upon the oceans and between the continents. […] It was the Cape of Good Hope specifically that symbolized for many centuries the two great formative frontiers of the modern world,’ which Mostert characterizes as ‘the oceanic barrier to the east on the one hand and on the other the more intangible frontier of consciousness, represented by Europe gaining a foothold at the tip of Africa.’ The ‘seam,’ writes De Kock is, by extension, ‘the place where difference and sameness are hitched together.’

This idea of a discrete battle between and betwixt cultural homogeneity and cultural difference feels key to your depiction of Pretoria, which tussles with its status as a kind of settled frontier, on the one hand, and open territory on the other, as you depict the space coming to terms with its organization, population and the kinds of cliché we employ to think through such sites. The onanistic influence of American culture seems key to such a line of thought; Pretoria’s suburbs are referred to as a kind of ‘new world’ soundtracked by American cinema, and Branko admits that ‘there was a time when [he] went to the movies just to listen,’ whilst citing Days of Heaven, Escape from the Planet of the Apes, Bette Davis and Gene Autry the ‘singing cowboy’ as keen points of influence. Whilst Branko’s line feels a good way in which to frame the power of an American Hollywood vernacular abroad, he also argues Joe’s affair with Ali as a direct product of cultural effect; of sports writing and its tendency towards a lionizing of its heroes (‘if it wasn’t for the calm world of the broadsheets,’ Branko suggests, Joe ‘would never have fallen in love with Ali’). Broadcasting, journalism and newsprint seem to be a kind of means of thinking through not just the ascendancy of European and American culture ‘at the tip of Africa,’ but also a seaming together of medias and minds; inspiration and action; cultural persona and local personality. The way Joe’s love of Ali does not exact a form of possession, but a kind of effected intimacy, say. Cinema also seems be a consistent means of exploring the machinery involved in that feeling. Branko holds the cinema as a space defined by the residue of human activity (‘the place smells of sweat, dust, boot polish, fruit gums’), and De Kock’s notion of the ‘seam’ also seems appropriate to your allusions to the cultural power of film. Sitting in the cinema as ‘the projector clatters at the back and an image reels on to the screen,’ the space essays a means of screening sameness in different places in this novelistic response to Pretoria’s urban personality, and seems essay a means of thinking through both Joe and Branko’s differing dependencies on different forms of popular culture. With all that in mind, we should perhaps unpick the predominance of cinema in The Distance….

Before we think on Jordan’s film in more detail, which we should certainly give some table-time, I was wondering if you could reflect a little further on the place of movies and moviegoing within this novel? The seaming of light and image that produces work of such power for Branko? The function of film in The Distance feels like another kind of tapestry on the make; is Branko’s want to quote film culture a graded echo of Joe’s dependency on the vernacular and vocabulary of ‘70s sports journalism? Branko’s relationship with film does tend toward the idea of ‘mending or patching,’ but also speaks to the notional forms of collage that Joe rehearses; a practice where we work to try and hide the hem of each individual image (I’m thinking of his want to hear a film, rather than watch one)…. In the contexts and contents of The Distance and its quilt of references, do you consider cinema another means of approaching such ideas? As another version of the solera process? Another ‘metaphor […] for how culture works’?

I.V. — You ask about the place of movies in the novel, but perhaps we could think about popular culture more broadly. The place of metaphor too.

Unsurprisingly, the preoccupations of my novel have become clearer to me in retrospect, and it now appears that it is centrally concerned with the detritus of popular culture, especially the American kind, in the minds of the characters and the dream life of the society around them. The scrapbooks are an obvious, tangible instance of a residue. And as you point out, Branko’s head is as full of film scraps as a cutting-room floor. That’s a nearly defunct metaphor, incidentally, as even those movies that are shot on film today are usually digitized for editing.

I must have given Branko a job in the movies, in somewhat obvious contrast to his bookish brother, so that I could play out on a small stage the tussle between print and film, newsprint and newsreel, paper and screen that is one of the great cultural dramas of our times. Some hyperbole is justified I think: we’re witnessing the displacement of the physical object from the centre of culture, a gradual process hastened recently by the coronavirus and its consequences. South Africa came late to television and this may have shaped my understanding of these shifts. Right now I recalled the first images of the moon landing on the front pages of our newspapers. How different it must have been to watch the event on television. Over the years of writing The Distance, as I worked repeatedly with the news cuttings and looked at boxing films online, I became fascinated by the difference between the modes, between the still photograph and the moving picture, and some of this is in the novel.

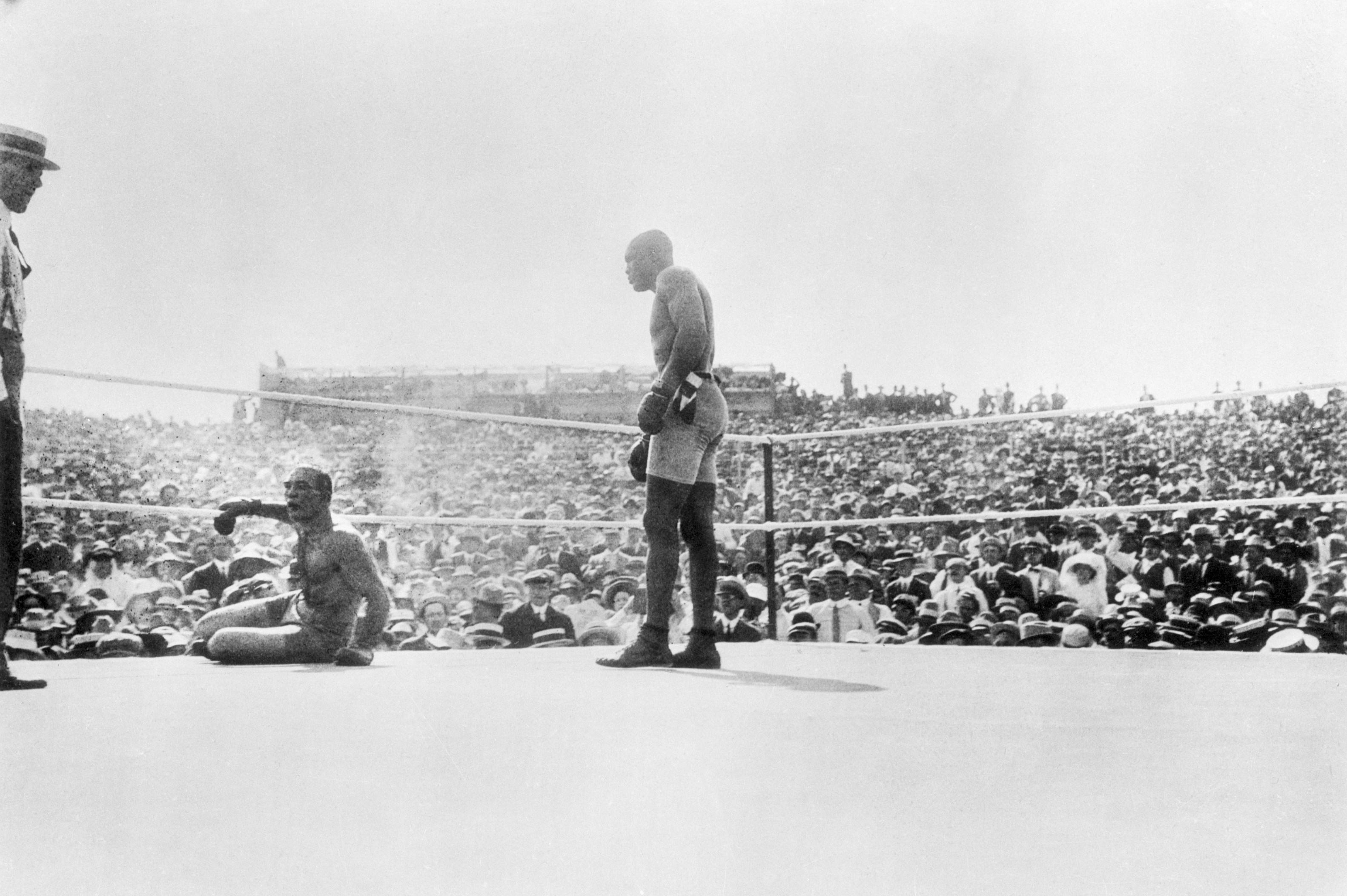

Neil Leifer is the sports photographer who took the famous photo of Ali standing over Sonny Liston after knocking him down in their return match (Lewiston, 1965). In a filmed interview, Leifer spoke revealingly about how that great photograph misrepresented the moment. The circumstances of his viewpoint at the ringside, the position of the boxers, the pressing of the shutter produced an image in which Ali appears to be standing over his fallen opponent, something the captions nearly always confirm. But when Leifer watched the film afterwards, he couldn’t isolate the tableau. Ali was constantly on the move, dancing around the ring. You could say that the famous moment exists only in the photograph. (In Chapter 13: ‘Limits’ Branko is planning to watch the fight: ‘There are things I’ve read about and would like to see for myself: the moment Ali stood over a fallen Liston.’ But he never gets round to it.)

Movies played a large and magical part in my childhood. Perhaps the absence of television heightened the experience of going to watch a film. What happens to all this imagery? How does it shape our attitudes and action? There’s a library of books on the subject and I’m no expert. What I do know is that film images linger with a peculiar intensity. This is true of books too, although the images—being verbal—are harder to call to mind. Nadine Gordimer was once asked about her literary influences, and she responded that all the crucial influences come from the books you read as a child—in her case including Gone with the Wind and Pepys’s Diary at the age of 12. Whether or not her answer was a typically deflective writer’s response on questions about influence, it directs attention to the corners of the bookshelf we tend to ignore. In The Distance (Chapter 6: ‘Collectors’) Branko is touchy about his low-brow tastes: ‘The blokes on the bottom shelf, Goodis, Chandler, Hammett, that’s me. Joe outgrew this crew and never thought much of my reading tastes afterwards.’ But are books that easy to outgrow? If Leslie Charteris and Simon Templar seem to occupy an inordinate amount of space in the novel, it’s because they did so in Joe’s boyhood.

Last night I read George Orwell’s essay ‘Raffles and Miss Blandish’ (1949), an astute and still provocative piece on the change in the ‘moral atmosphere’ of the crime novel signalled by writers like James Hadley Chase (who was not an American, by the way, although he wrote in ‘the American language,’ as Orwell puts it). In the section on Raffles, E.W. Hornung’s gentleman burglar, Orwell talks about the significance of the fact that Raffles plays cricket. He says that cricket ‘gives expression to a well-marked trait in the English character, the tendency to value “form” or “style” more highly than success.’ Regarding certain sports as ‘giving expression’ to qualities or values may be better than seeing them as ‘metaphors.’

If one must use metaphors, one should choose them carefully, as you reminded me at the start (via Joyce Carol Oates). Joe suggests that culture works like the solera process. Cultural products—styles? precepts? values? flavours?—are tapped down from high to low. What happens to them along the way: do they become more or less refined? In the manufacture of sherry, the qualities of the product become more predictable and consistent, perhaps at the expense of brilliance, but I think Joe means something different: they become adulterated, diffused, watered down. When someone like Joe uses terms like ‘high’ and ‘low’ in the vicinity of ‘culture’ that’s usually the implication.

There’s every possibility that culture works the other way round. That the styles, precepts, values, flavours filter upwards, are distilled from low to high, from popular to serious, if these terms can still be used. Movies are the prime example. Since the advent of the magic lantern, writers have been emulating films, trying to find ways of coopting or adapting moving-image modes.

In the same part of Chapter Six quoted above, Branko is reading Leslie Charteris, hoping to discover something about his brother’s mind and character. Rather than reading one book all the way through, he reads the first chapter in each of three books, and then the second. Channel-hopping, he calls it. But I wonder if a reader’s page-by-page advance through a book, possibly licking the tip of a finger from time to time, can ever be compared to the jump-cut produced on the screen by pressing a button on the remote.

IV. BOTTOM-SHELF SAINTS

(or THE SEAM, AGAIN)

Leslie Charteris is a good spotlight for thinking about reading as a form of channel-hopping; whether a reader’s (remote) control of a text can ever elicit the kind of editorial power through an ability to gloss between pages, between books. But given that Charteris’ name was (supposedly) a pseudonym lifted from the telephone directory, his inclusion here feels like an allusion to the forms of power we can pool from our ability to operate culture; to push the solera this way or that….

I wonder if you could speak to the place of control in the novel more broadly, in this sense, and, perhaps, expand upon the distinction between metaphor and expression you allude to? Charteris appears again in the book, in Chapter twelve—‘Inheritance’—Branko details the kind of committee writing that occurred under Leslie’s good name. Alongside a pile of paper matter, Branko glows over Joe’s ‘rat-eaten paperbacks,’ including a number of works in Charteris’ Saint series. ‘I sort the books by date of first publication,’ writes Branko; ‘from Enter the Saint published in 1930 to The Saint on TV in 1967.’

Branko reflects on Charteris’s ‘great fictional invention,’ Simon Templar; and, researching Charteris, ‘googling’ Templar, asks ‘What did I learn?’

This ‘bottom shelf’ hero is a curious parallel to Joe’s own object of adoration—his elevated icon, Ali—but I’m curious about the distinction between Joe’s want to be Charteris, and Branko’s want to see Ali; how embodiment and witness play out in the book as parallels to your line on expression and metaphor as two ways of reading the place of boxing in this novel?

This also seems be an idea that runs through your other fictions, whether we’re considering the place and purposes of the photographer, photograph and the subject photographed in Double Negative; or unfinished ideas, ‘unsettled accounts’ and your own habits as a reader in The Loss Library… This sense of the discrete difference between being and seeing; between doing and analysis; between the cultural work and culture as work; seems key to your writing, wholly significant to The Distance. Maybe this is just ‘literary rope-a-dope,’ to borrow a solid automobile of a phrase from Branko, I’d love to hear your thinking… How, in spite of the integrity and extent of Joe’s archival love affair with Ali, that mass of information seems to obscure a capacity for self-reflection and clear nostalgia. Control becomes remote, to forgive a clumsy play on words. The Distance has a broad (pop) cultural lexicon, but that language seems designed to obstruct more than it clarifies, perhaps?

This also brings us back to Jordan’s Overkill, something we’d said we’d return to. Initially dismissed by both Branko and Rita as a fan’s remake of Pulp Fiction, their viewing experience tends towards something other. A college (and collage) film, Jordan signs off as ‘Juwardi X’ on the titles, and this ‘speculative documentary about death’ becomes a means for Branko and Rita to think about what kinds of conversation and material they are entitled to discuss (Rita recalls the film’s initial reception as ‘exploitative’), and Branko can only think about himself and his own remembrances of objectification as the film shuttles on.

Here we’ve the scrapbook again (to circle back and end how we began), and I’d be curious to hear more about your sense of the literary collage and/or cut, as per your earlier prompt. But it’s also curious how the private and public are played out in tandem in Overkill, and the weight and gravitas of the former gets in the way of Branko’s ability to assess the quality and meaning of the film as a piece of work. In his response to Rita’s reading of the film, we get a brief inroad into Branko’s confoundment:

This experience of disorientation is heady, but provides a perfect counterpoint to our previous dialogue—the scrapbook, the collage, the cut; a quilt of ideas and images and De Kock’s sense of the seam or a seaming of things—we talked a little about the amassing of materials at the start of this conversation and, to end, perhaps we could think a little about the legibility thereof? About reading the seam, rather than writing one down…

![]()

![]()

I.V. — A power struggle was built into the book through the double narrative. Joe begins by pressuring his brother into a collaboration and trying to control his contribution, but the balance of power shifts as the story progresses, and by the end it is no longer clear who is in charge. Step back and the question of control can be directed to the writer. I said earlier that I started out with a single narrator, the writer Joe, trying to write some kind of essay about Muhammad Ali and some kind of memoir about his boyhood. When this proved too much for one narrator, a brother Branko was summoned into existence and tasked with writing the memoir. Is this the text dictating the terms? Take another step back—careful not to fall out of the ring—and the control finally rests with the reader, as every student of literary theory knows. Or at least the question of control must be settled between the reader and the text. As Branko puts it in a passage where he considers the boxing metaphor (important to our discussion): ‘Perhaps it’s the reader who’s in the other corner? But then the book stands between the two adversaries [writer and reader] like a punchbag. It cannot defend itself.’ To me this seems like an unnecessarily gloomy assessment of the text’s vulnerability by a narrator who still has much to learn about writing.

We both keep circling back to metaphor. Your introductory quote from Joyce Carol Oates must have served as concert pitch for the discussion. I’ve enjoyed trying to understand the metaphors we’ve been using for particular writing or meaning-making strategies: the seam, collage, channel-hopping and so on. I wonder though if the precise implications of these figures are as important as the broader impulse they reveal, which is to bring things together, to put them side by side. You’ll understand that this impulse and its opposite, to set apart, carry more weight than they otherwise might for someone who grew up in a divided society. I value culture as a synthetic process—the word ‘synthesis’ derives from the Greek for ‘place together.’ We could contrast this with ‘analysis,’ from the Greek for ‘unloose,’ the act of separating something into its constituent parts. Writers often stress the synthetic nature of their art. In my reading of the last few weeks alone, I came across this line in Eduardo Galeano’s The Book of Embraces: ‘Why does one write if not to put one’s pieces together?’ Or this in Gordimer, another writer I’ve mentioned before, in her Paris Review interview from 1979/80, collected in Women Writers at Work (edited by George Plimpton): ‘There are two ways to knit experience, which is what writing is about.’ She and the interviewer are discussing the work of Eudora Welty and Virginia Woolf, in relation to the writer’s focus inward on ‘one small area’ or outward on ‘wider subjects,’ and it’s interesting that in this context she uses a feminine metaphor like ‘knit experience’ and in such a direct, transitive way. You can almost see her taking up two pens.

‘Knitting’ and ‘mending’ are old craft images; we’ve used ‘patch,’ ‘quilt’ and ‘hem’ as well. ‘Montage’ and ‘collage’ seem more contemporary, but have a long history. In the 1920s and 30s, Walter Benjamin developed montage as a critical tool and made it the structuring principle of his Arcades Project (I’ve been discussing this recently with Jane Poyner and Joshua Hambleton-Jewell at Exeter University). We’ve come a long way from the radical use of such techniques by an artist like Max Ernst or a writer like John Dos Passos. Collage and montage are now everywhere in our visually saturated culture, shaping even the most popular forms, like advertising, and creating a disorienting surface that manages to be fragmented and seamless at once and more often than not conceals commercial and political messaging.

Is there still life in these methods? Perhaps there is more for the novelist to play with than the visual artist. Writers, after a century of trying to emulate film, are left sharpening the old tools. Juwardi X’s Overkill: A speculative documentary about death is a visual work constructed by montage. But the crucial thing about it is that it exists only in language. The film footage of the Marikana Massacre (16 August 2012) is some of the most violent and shocking imagery in South African political history. I was shaken to see it on the evening news and still find it difficult to watch. In Juwardi’s film, some of this footage is spliced together with scenes from Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969). I wonder what the effects of an actual film of this kind would be. On the page, cast in words, the images do not have a painfully direct connection to real people and acts. The reader’s response is shaped less by the imaginative images conjured than by the qualities of the language itself, the register and syntax, the sound and tone. Language draws an interpretive, transformative veil over the real and that is one of its beauties.

As you point out, Branko does not know how to read Overkill. His own image in the film, no less than the image of his brother, throws him off balance. He finds himself among the familiar images of the massacre—‘but it’s different now that it’s no longer news.’ Our technologies allow us to insert ourselves into the record in this way, but not everyone has the inclination. Perhaps Branko’s confoundment (a good way to put it) arises partly from his anxiety about his son’s ability and willingness to treat the archive as raw material, to erase the quotation marks and delete the endnotes, to ‘operate culture’ in the era of mashups and remixes as if everything cuts with everything else. Branko, the devotee, sitting in a darkened theatre with his eyes closed, listening to a film, is an increasingly archaic figure. That goes double for the clipper of stories on newsprint.

Does the physical archive in the novel obscure more than it reveals? Perhaps. It brings the wider world into the confines of a small story and introduces political and social questions that might otherwise be easier to avoid. But the archive is flawed, it is personal, partial, idiosyncratic, largely ‘exotic,’ that is, originating in a distant foreign country, and full of gaps and silences. It is an irrefutable record of the past, but it cannot possibly complete the picture.

I wonder if you could speak to the place of control in the novel more broadly, in this sense, and, perhaps, expand upon the distinction between metaphor and expression you allude to? Charteris appears again in the book, in Chapter twelve—‘Inheritance’—Branko details the kind of committee writing that occurred under Leslie’s good name. Alongside a pile of paper matter, Branko glows over Joe’s ‘rat-eaten paperbacks,’ including a number of works in Charteris’ Saint series. ‘I sort the books by date of first publication,’ writes Branko; ‘from Enter the Saint published in 1930 to The Saint on TV in 1967.’

This last one is not actually by Charteris: it’s Fleming Lee’s adaptation of two stories from the TV series starring Roger Moore. Charteris stopped writing The Saint books in 1963, although he edited and revised some that were written afterwards by other people and published under his name, including this one. In his foreword to Lee’s book, Charteris calls it ‘an interesting and perhaps unprecedented experiment in teamwork ... I have done the back-seat driving and added a few typical flourishes of my own.’

The Saint books were popular for more than forty years and some of them ran to twenty impressions and half a dozen new editions. I reorder Joe’s collection by the date in which they actually appeared so that I can see the different imprints and series designs. The best covers were painted by J Pollack for the Pan editions of the early fifties and show Templar in a collar and tie and fedora. His eyebrow is cocked, and his lip quirked. He looks ironic and debonair, and cheerfully, uncomplicatedly masculine. According to the back cover note he is a ‘man of superb recklessness / strange heroisms / and impossible ideals.’

Branko reflects on Charteris’s ‘great fictional invention,’ Simon Templar; and, researching Charteris, ‘googling’ Templar, asks ‘What did I learn?’

Simon Templar had an alter ego called Sebastian Toombs. That he yearned to write poetry. That he was a subversive of a kind, a left-leaning Robin Hood, the scourge of the powerful and champion of the poor, who loved to humiliate the magnates and arms dealers and give the big shots their comeuppance.

What did I miss? The obvious. It wasn’t Templar my brother wanted to be. It was Charteris.

This ‘bottom shelf’ hero is a curious parallel to Joe’s own object of adoration—his elevated icon, Ali—but I’m curious about the distinction between Joe’s want to be Charteris, and Branko’s want to see Ali; how embodiment and witness play out in the book as parallels to your line on expression and metaphor as two ways of reading the place of boxing in this novel?

This also seems be an idea that runs through your other fictions, whether we’re considering the place and purposes of the photographer, photograph and the subject photographed in Double Negative; or unfinished ideas, ‘unsettled accounts’ and your own habits as a reader in The Loss Library… This sense of the discrete difference between being and seeing; between doing and analysis; between the cultural work and culture as work; seems key to your writing, wholly significant to The Distance. Maybe this is just ‘literary rope-a-dope,’ to borrow a solid automobile of a phrase from Branko, I’d love to hear your thinking… How, in spite of the integrity and extent of Joe’s archival love affair with Ali, that mass of information seems to obscure a capacity for self-reflection and clear nostalgia. Control becomes remote, to forgive a clumsy play on words. The Distance has a broad (pop) cultural lexicon, but that language seems designed to obstruct more than it clarifies, perhaps?

This also brings us back to Jordan’s Overkill, something we’d said we’d return to. Initially dismissed by both Branko and Rita as a fan’s remake of Pulp Fiction, their viewing experience tends towards something other. A college (and collage) film, Jordan signs off as ‘Juwardi X’ on the titles, and this ‘speculative documentary about death’ becomes a means for Branko and Rita to think about what kinds of conversation and material they are entitled to discuss (Rita recalls the film’s initial reception as ‘exploitative’), and Branko can only think about himself and his own remembrances of objectification as the film shuttles on.

It’s hard to say what it’s about. Mainly it seems to be home-movie footage from the family archive—he’s been snooping around my hard drives, the little shit—intercut with the cheerier parts of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. There’s cellphone footage of me and Rita going over the household budget intercut with the bicycle scene. Paul Newman in the saddle, Katherine Ross on the handlebars. Now he’s showing off—look ma, no hands—while she watches from the barn. The soundtrack’s been stripped out but ‘Raindrops Keep Falling on my Head’ plays in the back of my mind. I fell in love with Katherine Ross when I saw this as a teenager. I would get horny thinking of her while I gazed at Kathy van Deventer who sat in front of me in Guidance. Nothing seems to fit. And there’s Jordan when he played a wizard in the school play and Katherine Ross as Etta Place in the schoolroom. I want to hear what she’s telling the kids but it’s drowned out by some hectic bass piece. Could be the Prisoners of Strange.

Now the pace changes and the screen becomes bloody. Surgical procedures. In graphic detail, as they say.

I think it’s Botched, Rita says, that’s the one about people who’ve fucked up their bodies with cosmetic surgery.

Is it about me? The surgeon as editor. Or rather the editor as surgeon.

[…]

A couple of shots of Ali and Foreman. What the fuck! I say. That’s my stuff. He’s rumbling in my jungle.

It’s not about boxing, Rita says, it’s about state violence and the violence of capital, and also the violence of the image and the violence done to the black body. That’s how he explained it.

We watch in silence.

It’s pretty good, she says.

Sure.

Here we’ve the scrapbook again (to circle back and end how we began), and I’d be curious to hear more about your sense of the literary collage and/or cut, as per your earlier prompt. But it’s also curious how the private and public are played out in tandem in Overkill, and the weight and gravitas of the former gets in the way of Branko’s ability to assess the quality and meaning of the film as a piece of work. In his response to Rita’s reading of the film, we get a brief inroad into Branko’s confoundment:

I can’t tell if she’s criticizing the film or coming to its defense. Rita said there was a fuss about it, people thought it was exploitative. [What were] the scenes that upset them? Maybe there are things we can’t talk about and the retelling only redoubles the insult. […] Who do I mean by ‘we.’ I look over her head into Juwardi’s face and for a moment I think we’re exchanging a meaningful glance, but then I see that his eyes are closed.

This experience of disorientation is heady, but provides a perfect counterpoint to our previous dialogue—the scrapbook, the collage, the cut; a quilt of ideas and images and De Kock’s sense of the seam or a seaming of things—we talked a little about the amassing of materials at the start of this conversation and, to end, perhaps we could think a little about the legibility thereof? About reading the seam, rather than writing one down…

I.V. — A power struggle was built into the book through the double narrative. Joe begins by pressuring his brother into a collaboration and trying to control his contribution, but the balance of power shifts as the story progresses, and by the end it is no longer clear who is in charge. Step back and the question of control can be directed to the writer. I said earlier that I started out with a single narrator, the writer Joe, trying to write some kind of essay about Muhammad Ali and some kind of memoir about his boyhood. When this proved too much for one narrator, a brother Branko was summoned into existence and tasked with writing the memoir. Is this the text dictating the terms? Take another step back—careful not to fall out of the ring—and the control finally rests with the reader, as every student of literary theory knows. Or at least the question of control must be settled between the reader and the text. As Branko puts it in a passage where he considers the boxing metaphor (important to our discussion): ‘Perhaps it’s the reader who’s in the other corner? But then the book stands between the two adversaries [writer and reader] like a punchbag. It cannot defend itself.’ To me this seems like an unnecessarily gloomy assessment of the text’s vulnerability by a narrator who still has much to learn about writing.

We both keep circling back to metaphor. Your introductory quote from Joyce Carol Oates must have served as concert pitch for the discussion. I’ve enjoyed trying to understand the metaphors we’ve been using for particular writing or meaning-making strategies: the seam, collage, channel-hopping and so on. I wonder though if the precise implications of these figures are as important as the broader impulse they reveal, which is to bring things together, to put them side by side. You’ll understand that this impulse and its opposite, to set apart, carry more weight than they otherwise might for someone who grew up in a divided society. I value culture as a synthetic process—the word ‘synthesis’ derives from the Greek for ‘place together.’ We could contrast this with ‘analysis,’ from the Greek for ‘unloose,’ the act of separating something into its constituent parts. Writers often stress the synthetic nature of their art. In my reading of the last few weeks alone, I came across this line in Eduardo Galeano’s The Book of Embraces: ‘Why does one write if not to put one’s pieces together?’ Or this in Gordimer, another writer I’ve mentioned before, in her Paris Review interview from 1979/80, collected in Women Writers at Work (edited by George Plimpton): ‘There are two ways to knit experience, which is what writing is about.’ She and the interviewer are discussing the work of Eudora Welty and Virginia Woolf, in relation to the writer’s focus inward on ‘one small area’ or outward on ‘wider subjects,’ and it’s interesting that in this context she uses a feminine metaphor like ‘knit experience’ and in such a direct, transitive way. You can almost see her taking up two pens.

‘Knitting’ and ‘mending’ are old craft images; we’ve used ‘patch,’ ‘quilt’ and ‘hem’ as well. ‘Montage’ and ‘collage’ seem more contemporary, but have a long history. In the 1920s and 30s, Walter Benjamin developed montage as a critical tool and made it the structuring principle of his Arcades Project (I’ve been discussing this recently with Jane Poyner and Joshua Hambleton-Jewell at Exeter University). We’ve come a long way from the radical use of such techniques by an artist like Max Ernst or a writer like John Dos Passos. Collage and montage are now everywhere in our visually saturated culture, shaping even the most popular forms, like advertising, and creating a disorienting surface that manages to be fragmented and seamless at once and more often than not conceals commercial and political messaging.

Is there still life in these methods? Perhaps there is more for the novelist to play with than the visual artist. Writers, after a century of trying to emulate film, are left sharpening the old tools. Juwardi X’s Overkill: A speculative documentary about death is a visual work constructed by montage. But the crucial thing about it is that it exists only in language. The film footage of the Marikana Massacre (16 August 2012) is some of the most violent and shocking imagery in South African political history. I was shaken to see it on the evening news and still find it difficult to watch. In Juwardi’s film, some of this footage is spliced together with scenes from Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969). I wonder what the effects of an actual film of this kind would be. On the page, cast in words, the images do not have a painfully direct connection to real people and acts. The reader’s response is shaped less by the imaginative images conjured than by the qualities of the language itself, the register and syntax, the sound and tone. Language draws an interpretive, transformative veil over the real and that is one of its beauties.

As you point out, Branko does not know how to read Overkill. His own image in the film, no less than the image of his brother, throws him off balance. He finds himself among the familiar images of the massacre—‘but it’s different now that it’s no longer news.’ Our technologies allow us to insert ourselves into the record in this way, but not everyone has the inclination. Perhaps Branko’s confoundment (a good way to put it) arises partly from his anxiety about his son’s ability and willingness to treat the archive as raw material, to erase the quotation marks and delete the endnotes, to ‘operate culture’ in the era of mashups and remixes as if everything cuts with everything else. Branko, the devotee, sitting in a darkened theatre with his eyes closed, listening to a film, is an increasingly archaic figure. That goes double for the clipper of stories on newsprint.

Does the physical archive in the novel obscure more than it reveals? Perhaps. It brings the wider world into the confines of a small story and introduces political and social questions that might otherwise be easier to avoid. But the archive is flawed, it is personal, partial, idiosyncratic, largely ‘exotic,’ that is, originating in a distant foreign country, and full of gaps and silences. It is an irrefutable record of the past, but it cannot possibly complete the picture.

Ivan VLADISLAVIC was born in Pretoria in 1957 and lives in Johannesburg. His books include the novels The Restless Supermarket, The Exploded View and Double Negative, and the story collections 101 Detectives and Flashback Hotel. In 2006, he published Portrait with Keys, a sequence of documentary texts on Johannesburg. He has edited books on architecture and art, and sometimes works with artists and photographers. TJ/Double Negative, a joint project with photographer David Goldblatt, received the 2011 Kraszna-Krausz Award for best photography book. His work has also won the Sunday Times Fiction Prize, the Alan Paton Award, and Yale University’s Windham-Campbell Prize for fiction. He is a distinguished professor in creative writing at the University of the Witwatersrand.