The FIGHT

of the CENTURY;

Ivan VLADISLAVIC

an excerpt from a novel called The Distance

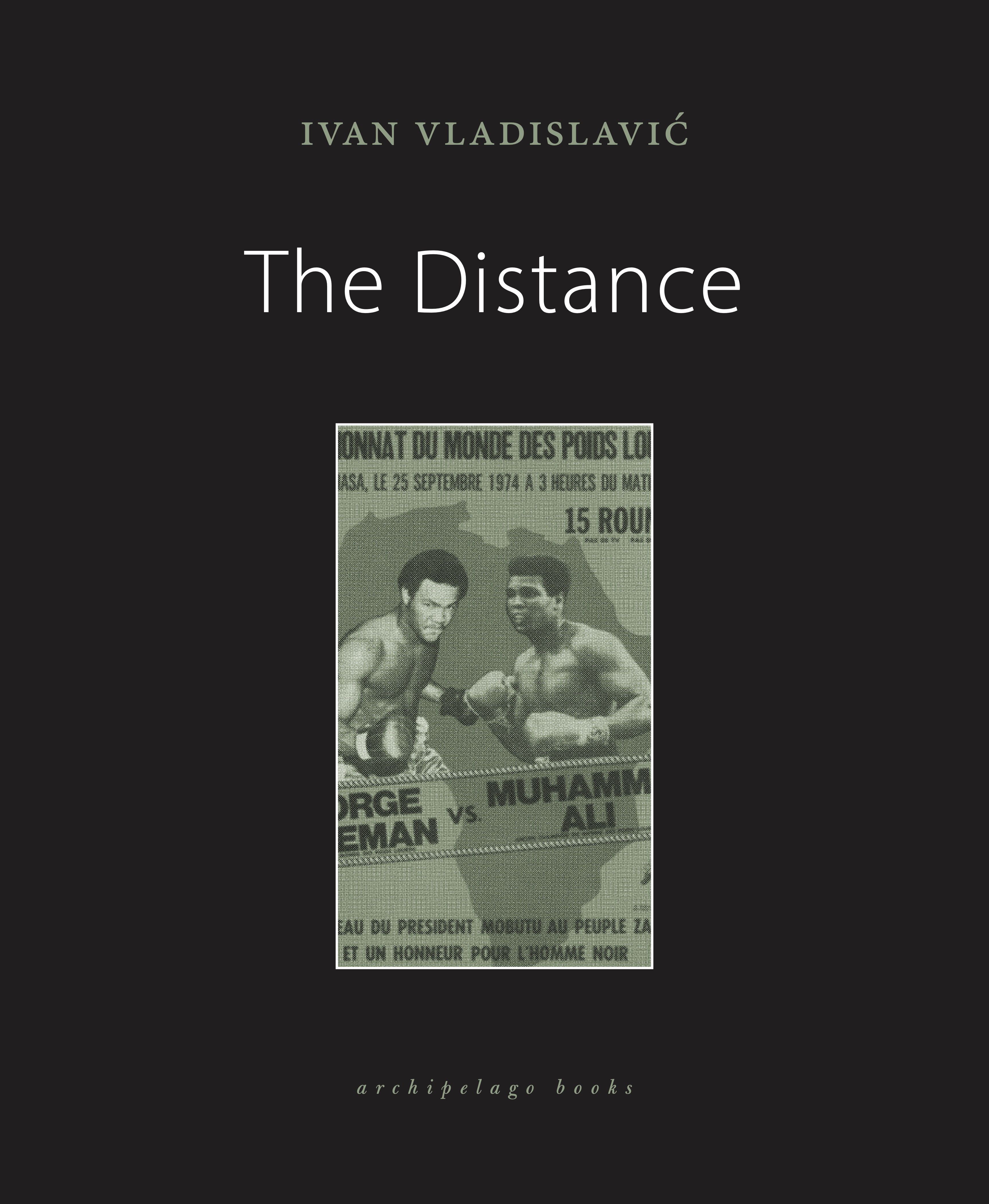

In his youth in 1970s suburban Pretoria, during a pivotal decade in South African history amid growing resistance to apartheid, Joe falls in love with Muhammad Ali. Diligently scrapbooking newspaper clippings of his hero, Ivan Vladislavic’s The Distance (Archipelago Books) records and imbibes the showman’s inimitable brand of resistance. Forty years later, digging out his yellowed archive of Ali clippings and comics, Joe sets out to write a memoir of his childhood. Calling upon his brother Branko for help, their two voices interweave to unearth a shared past, and a new perspective on the realities of growing up with a conservative father in a segregated society. Reconstructing a world of bioscopes, Formica tabletops, Ovaltine, and drop-offs in their father’s Ford Zephyr, conjuring the textures of childhood, what emerges is a collision of memories, patching the gulf between past and present. Meaning arises in the gaps between fact and imagination, and words themselves become markers of the past, charting an era of racism into the turbulent present. In this formally inventive, fragmented novel, Vladislavic evokes the beauty, and the strangeness, of remembering and forgetting, exploring the various forms of violence and rebellion, and what it means to be at odds with one’s surroundings.

Hotel runs an exclusive excerpt from the novel below...

The Distance can be ordered direct from the publisher here.

Hotel runs an exclusive excerpt from the novel below...

The commander of South Vietnamese forces in Laos said today that his troop had seized three main junctions on the Ho Chi Minh trail and were achieving the two objectives of their drive—destroying North Vietnamese bases and cutting the supply network.

(Pretoria News, March 1971)

Joe

In the spring of 1970, I fell in love with Muhammad Ali. This love, the intense, unconditional kind of love we call hero worship, was tested in the new year when Ali fought Joe Frazier at Madison Square Garden. I was at high school in Verwoerdburg, which felt as far from the ringside as you could get, but I read every scrap of news about the big event and never for a moment doubted that Ali would win. As it happened, he was beaten for the first time in his professional career.

It must have been the unprecedented fuss around the Ali vs Frazier fight that turned me, like so many others who’d taken no interest in boxing before then, into a fan. ‘The Fight of the Century’ was one of the first global sporting spectacles, a Hollywood-style bout that captured the public imagination like no sports event before it. In the words of reporter Solly Jasven, it was as significant to the Wall Street Journal as it was to Ring magazine, and it generated what he called the big money excitement.

I don’t know what I thought of Ali before the Fight of the Century, but I came from a newspaper-reading family and had started reading a daily when I was still at primary school, so I must have come across him in the press, and not just on the sports pages. In March 1967, after he’d refused to serve in the US army, the World Boxing Association and the New York State Athletic Commission had stripped him of his world heavyweight title. This was big news in South Africa, but I cannot say what impression it made on my nine-year-old self.

Although Ali was absent from the ring for more than three years, he was not idle: he was on the lecture and talk-show circuit, he appeared in commercials, he even had a stint in a short-lived Broadway musical called Buck White. In short, he was doing the things celebrities of all kinds now do as a matter of course to keep their names and faces in the spotlight and build their ‘brands.’ He went from the boxing ring to the three-ring circus of endorsements and appearances. He was also speaking in mosques and supporting the black Muslim cause. But very little of this activity, whether meant in jest or in earnest, was visible from South Africa.

In 1970, when I was twelve, a Federal court restored Ali’s boxing licence. His first comeback fight was against Jerry Quarry in Atlanta and he won on a TKO in the third round. Six weeks later he beat Oscar Bonavena and that set up the title fight against Frazier in March the following year. It was a match Frazier had promised him if his boxing licence was ever returned.

We had no television in South Africa then and our news came from the radio and the newspapers. The Fight of the Century produced an avalanche of coverage in the press. My Dad read the daily Pretoria News and two weeklies, the Sunday Times and the Sunday Express, and so these were my main sources of information. In the buildup to the fight I started to collect cuttings and for the next five years I kept everything about Ali that I could lay my hands on, trimming hundreds of articles out of the broadsheets and pasting them into scrapbooks. Forty years later, these books are spread out on a trestle table beside my desk as I’m writing this. Let me also confess: I’m writing this because the scrapbooks exist.

The heart of my archive is three Eclipse drawing books with tracing-paper sheets between the leaves. These books have buff cardboard covers printed with the Eclipse trademarks and the obligatory bilingual ‘drawing book’ and ‘tekenboek.’ In the middle of each cover is a hand-drawn title: ALI I, ALI II and ALI III. The newsprint is tobacco-leaf brown and crackly. When I rub it between my fingers, I fancy that the boy who first read these reports and I are one and the same person.

Joe

On the cover of the first scrapbook—a book of scraps, about scraps—I spelt out the word ALI in upright capitals using red double-sided tape from my father’s garage. When this tape dried out and fell off like an old scab, leaving a tender trace of the name on the board, I outlined each letter in black Koki pen to restore its definition. The numeral after the name must have been added when the growing volume of cuttings demanded a second scrapbook.

The first cutting in ALI I is headlined in red ‘The Fight of the Century.’ It was published the day before the fight. Like most of the cuttings this one is unattributed, but judging by the typeface and layout it was taken from the Sunday Times.

It’s a busy page. There are drawings of Frazier and Ali side by side and between them, under the headline ‘How the Fighters Compare,’ the stats on weight, height and reach, the dimensions of waist, thigh, chest (normal and expanded), fist and biceps, and finally age. Boxing writers call this the Tale of the Tape. Unfurled below are ‘Fight Histories’ with the highlights of each boxer’s career accompanied by a photograph. The picture of Joe Frazier knocking out Bob Foster, his most recent challenger, is not familiar. But the other is one of the most recognizable images in sporting history: Cassius Clay standing over a prone Sonny Liston after knocking him out in the first round of their return match in May 1965. Clay’s right forearm is angled across his chest, as if he’s still following through, and he’s looking down at Liston with a snarl on his lips. It’s a stance that makes perfectly clear what a boxing match is about. Ali later told a reporter he was saying: Get up and fight, you bum!

The rest of the page is devoted to Frazier, and his comments reveal why the interest in the fight was so intense. Clay lost his licence because he refused to be drafted into the United States Army. That’s something I can’t have sympathy about. Frazier goes on to tell David Wright how he himself tried to join the Marines when he was just fifteen and was turned down because he couldn’t cope with the IQ tests.

Further on he describes his childhood as the son of a one-armed sharecropper in South Carolina, his working life on the killing floor of a slaughterhouse in Philadelphia, where he began boxing to keep his weight down, and the importance of the Bible in his life. Recently I’ve been kinda stuck on the seventh chapter of Judges—where Gideon is fighting those tribes and everybody. Gideon only had a few men against thousands, but he won the war because he had the Lord on his side. That’s just how I feel about this fight with Cassius Clay.

Judges 7 is one of those cheerfully brutal Biblical episodes in which the righteous smite their enemies. In this case, the Lord delivers the Midianites into the hands of Israel. He instructs Gideon to choose a conspicuously small army of men, no more than three hundred from among the thousands. So Gideon leads a crowd of men to the water, dismisses those who kneel down to drink and recruits only those who lap the water up with their tongues ‘as a dog lappeth’. These men are sent out against the enemy camp armed with trumpets and lamps inside pitchers, and in due course the Midianites are well and truly smitten. Their princes Oreb and Zeeb are slain and their heads cut off and brought to Gideon on the banks of the Jordan.

The Book of Judges is a cloudy lens, but if you squint through it what comes into focus is Frazier’s aversion to a man who had renounced Christianity for a ‘foreign religion’ and refused to fight in the Vietnam War.

The week before the fight, Frazier and Ali were on the cover of Time magazine under the headline ‘The $5,000,000 Fighters.’ The story, based on hours of interviews with both boxers, summed up the simple symbolism of the fight: Shrewd prefight publicity has turned the billing into Frazier the good citizen v. Ali the draft dodger, Frazier the white man’s champ v. Ali the great black hope, Frazier the quiet loner v. Ali the irrepressible loudmouth, Frazier the simple Bible-reading Baptist v. Ali the slogan-spouting Black Muslim.

On 8 March 1971, 20 000 people packed into Madison Square Garden to watch what turned out to be one of the most memorable heavy-weight boxing matches in history. The fight went the distance and all three judges scored it in favour of Frazier.

It’s the happiest day of my life, my father said. Except for the day I married your mother, the day she gave birth to your sister, and the day I bought my first car, a ’38 Chevy with a dickey seat. Jissie that was a beautiful car.

Joe

The Fight of the Century was promoted by a theatrical agent called Jerry Perenchio, who blithely told the world: I really don’t know the first thing about boxing.

Perenchio was an innovator. Even before the fight he had the idea of auctioning off the fighters’ shoes and gloves. If a movie studio can auction off Judy Garland’s red slippers ... these things ought to be worth something. You’ve got to throw away the book on this fight. This one transcends boxing—it’s a show business spectacular.

The purists were not pleased with the turn boxing had taken. They railed against the playacting, the vaudeville routines and costume changes, and their resentment just fuelled the fire. The circus was in town and there was no turning back. At the head of the parade, fitting the new style like a fist in a glove, was Muhammad Ali. He had been annoying the authorities for years: his showboating at the weigh-in for the first Liston fight had seen him removed from the venue and fined. But this seemed innocuous by comparison with the carnival atmosphere before the Frazier fight. Time magazine’s description of Ali’s retinue, published on the eve of the fight, captures it vividly: There is Bundini, the cornerman and personal mystic who calls him ‘the Blessing of the Planet’; a handler whose sole job is to comb Ali’s hair; assorted grim-faced Muslim operatives; imperturbable Angelo Dundee, his trainer since 1960; Norman Mailer; Actor Burt Lancaster; Cash Clay Sr. in red velvet bell-bottoms, red satin shirt and a plantation straw hat; the Major, a high roller from Philly who tools around in a Duesenberg; and Brother Rahaman Ali (formerly known as Rudolph Valentino Clay), his yeah-man. Ali had said before that white America was unsettled by the spectacle of black people with money to burn, by the men in mink coats and hats, the women in spangled gowns, the customized Cadillacs.

The sight of two men pummelling one another senseless for prize money must always have attracted the merely or morbidly curious, those with no understanding of the finer points and a taste for blood. But as the era of the mass media dawned and boxing became less like sport and more like entertainment, it found a new audience among people like me, the know-nothing fans who could hardly tell a hook from a jab.

While boxing in general did not appeal to me, my interest in Muhammad Ali was all-consuming. I might have forgotten the full extent of it, as we forget so much of what we thought and did in the past, had it not been for the archive of cuttings.

When my obsession faded away, I put the scrapbooks and loose cuttings in a cardboard box. In time, I moved out of my parents’ house and went to university, and I left the box behind in a cupboard. But the past is not so easily disposed of. I wanted to be a writer and the box came to seem like a key to my past. It was a journal written in code, the most complete record of my teenage life to which I had access, despite the fact that I was not mentioned in it once. I retrieved it from my parents’ house and carried it with me to a dozen homes of my own.

Over twenty years, I went through the scrapbooks so many times I lost track, intending to write something about them, intrigued anew by what they might reveal of the world I grew up in. A book eluded me. Why? I wasn’t sure what I was looking for: I didn’t know what questions to ask of these yellowed pages. Each pass through the archive produced some sketchy drafts of this chapter and that passage. It also produced pages and pages of notes and outlines, scattered associations and half-formed structures, summaries and quotations, all added to a lever-arch file, and then revised and annotated at each revisiting. Finally, this file stuffed with contradictory notes became as intractable an obstacle as the scrapbooks themselves, a shadow of obscure intent over the blank page on which a book might actually start.

In the spring of 1970, I fell in love with Muhammad Ali. This love, the intense, unconditional kind of love we call hero worship, was tested in the new year when Ali fought Joe Frazier at Madison Square Garden. I was at high school in Verwoerdburg, which felt as far from the ringside as you could get, but I read every scrap of news about the big event and never for a moment doubted that Ali would win. As it happened, he was beaten for the first time in his professional career.

It must have been the unprecedented fuss around the Ali vs Frazier fight that turned me, like so many others who’d taken no interest in boxing before then, into a fan. ‘The Fight of the Century’ was one of the first global sporting spectacles, a Hollywood-style bout that captured the public imagination like no sports event before it. In the words of reporter Solly Jasven, it was as significant to the Wall Street Journal as it was to Ring magazine, and it generated what he called the big money excitement.

I don’t know what I thought of Ali before the Fight of the Century, but I came from a newspaper-reading family and had started reading a daily when I was still at primary school, so I must have come across him in the press, and not just on the sports pages. In March 1967, after he’d refused to serve in the US army, the World Boxing Association and the New York State Athletic Commission had stripped him of his world heavyweight title. This was big news in South Africa, but I cannot say what impression it made on my nine-year-old self.

Although Ali was absent from the ring for more than three years, he was not idle: he was on the lecture and talk-show circuit, he appeared in commercials, he even had a stint in a short-lived Broadway musical called Buck White. In short, he was doing the things celebrities of all kinds now do as a matter of course to keep their names and faces in the spotlight and build their ‘brands.’ He went from the boxing ring to the three-ring circus of endorsements and appearances. He was also speaking in mosques and supporting the black Muslim cause. But very little of this activity, whether meant in jest or in earnest, was visible from South Africa.

In 1970, when I was twelve, a Federal court restored Ali’s boxing licence. His first comeback fight was against Jerry Quarry in Atlanta and he won on a TKO in the third round. Six weeks later he beat Oscar Bonavena and that set up the title fight against Frazier in March the following year. It was a match Frazier had promised him if his boxing licence was ever returned.

We had no television in South Africa then and our news came from the radio and the newspapers. The Fight of the Century produced an avalanche of coverage in the press. My Dad read the daily Pretoria News and two weeklies, the Sunday Times and the Sunday Express, and so these were my main sources of information. In the buildup to the fight I started to collect cuttings and for the next five years I kept everything about Ali that I could lay my hands on, trimming hundreds of articles out of the broadsheets and pasting them into scrapbooks. Forty years later, these books are spread out on a trestle table beside my desk as I’m writing this. Let me also confess: I’m writing this because the scrapbooks exist.

The heart of my archive is three Eclipse drawing books with tracing-paper sheets between the leaves. These books have buff cardboard covers printed with the Eclipse trademarks and the obligatory bilingual ‘drawing book’ and ‘tekenboek.’ In the middle of each cover is a hand-drawn title: ALI I, ALI II and ALI III. The newsprint is tobacco-leaf brown and crackly. When I rub it between my fingers, I fancy that the boy who first read these reports and I are one and the same person.

Branko

I am the sportsman in the family. My brother Joe doesn’t mind kicking a soccer ball around in the yard, but when I need him to keep goal while I practise my penalties he’s got his nose in a book. Now all of a sudden he’s a boxing fan. Not that I’ve seen a lot of boxing myself. I’ve been to a couple of Golden Gloves tournaments at Berea Park with my cousin Kelvin, where they put up a ring on the cricket pitch in front of the grandstand. But we prefer the rofstoei in the Pretoria City Hall.

The thing about wrestling is the rules are easy to understand. If Jan Wilkens is on the bill, you know he’s going to win. He’s a huge Afrikaner and he’s the South African champion. Kelvin always shouts for Wilkens. My guy is Rio Rivers. He doesn’t often win but he puts up a good fight. The last time my cousin and I went to the wrestling, Dad insisted we take along Joe and Rollie—that’s Kelvin’s little brother. It was a fiasco. Joe started rooting for Sammy Cohen. Sammy’s a pile of blubber in a black leotard. He looks like he hasn’t slept for three days and he always loses. That’s his part to play. Joe doesn’t get the principle: you’re not supposed to support the bums.

And now this thing with Ali. It comes over him like the measles. The boxing bug is going around because of the upcoming fight between Ali and Frazier. Naturally I support Smokin’ Joe. I would support him in any case, but the fact that my little brother has picked the other corner is a bonus. Another chance to get under his skin.

Joe Frazier’s going to give Cassius Clay a boxing lesson, Dad says. He’s going to knock seven kinds of crap out of that loudmouth.

Eight kinds, I say.

And Mom says, Watch your mouth. Even though eight is just a number.

Dad won’t say Muhammad Ali. Over my dead body. It’s always Cassius Clay. It drives my brother to tears of frustration. Sometimes he goes out in the yard behind the servants’ quarters and smashes tomato boxes with a lead pipe.

Sport is my thing and I wish he’d leave it alone. My plan is to win the Tour de France one day. I prefer road racing but I join the track season to keep fit. Cycling is not a popular sport. If we’re lucky fifty or sixty riders turn up at the Pilditch track in Pretoria West on a Friday evening, most of them seniors, and a handful of us in the schoolboy ranks. Juveniles, they call us, a stupid term you would never apply to yourself. The stands are nearly empty: the wives and girlfriends and mothers cluster together in a few rows with crocheted blankets over their knees. Ten rows back Joe is sitting alone under the icy corrugated-iron roof, wearing a knitted cap with an enormous pompom. He’d rather be at home but Dad says: You boys have got to stick up for one another. When the starter’s pistol goes or the timekeeper rings the bell for the last lap, he pretends to watch. He’s half interested in the Devil-Take-the-Hindmost because of the name, but mainly he’s reading a book in his lap, struggling in his black leather gloves to turn the pages of The Canterbury Tales or David Copperfield. The explosive pompom, the biggest one Mom ever made, hovers over his head like an unhappy fate.

When I go to bed, I find him shadow-boxing. He’s supposed to be sleeping, but he’s got the desk lamp swivelled to cast a shadow on the wall next to the window. Bobbing and weaving, he says.

Ja, I say, float like a bumblebee.

Joe

On the cover of the first scrapbook—a book of scraps, about scraps—I spelt out the word ALI in upright capitals using red double-sided tape from my father’s garage. When this tape dried out and fell off like an old scab, leaving a tender trace of the name on the board, I outlined each letter in black Koki pen to restore its definition. The numeral after the name must have been added when the growing volume of cuttings demanded a second scrapbook.

The first cutting in ALI I is headlined in red ‘The Fight of the Century.’ It was published the day before the fight. Like most of the cuttings this one is unattributed, but judging by the typeface and layout it was taken from the Sunday Times.

It’s a busy page. There are drawings of Frazier and Ali side by side and between them, under the headline ‘How the Fighters Compare,’ the stats on weight, height and reach, the dimensions of waist, thigh, chest (normal and expanded), fist and biceps, and finally age. Boxing writers call this the Tale of the Tape. Unfurled below are ‘Fight Histories’ with the highlights of each boxer’s career accompanied by a photograph. The picture of Joe Frazier knocking out Bob Foster, his most recent challenger, is not familiar. But the other is one of the most recognizable images in sporting history: Cassius Clay standing over a prone Sonny Liston after knocking him out in the first round of their return match in May 1965. Clay’s right forearm is angled across his chest, as if he’s still following through, and he’s looking down at Liston with a snarl on his lips. It’s a stance that makes perfectly clear what a boxing match is about. Ali later told a reporter he was saying: Get up and fight, you bum!

The rest of the page is devoted to Frazier, and his comments reveal why the interest in the fight was so intense. Clay lost his licence because he refused to be drafted into the United States Army. That’s something I can’t have sympathy about. Frazier goes on to tell David Wright how he himself tried to join the Marines when he was just fifteen and was turned down because he couldn’t cope with the IQ tests.

Further on he describes his childhood as the son of a one-armed sharecropper in South Carolina, his working life on the killing floor of a slaughterhouse in Philadelphia, where he began boxing to keep his weight down, and the importance of the Bible in his life. Recently I’ve been kinda stuck on the seventh chapter of Judges—where Gideon is fighting those tribes and everybody. Gideon only had a few men against thousands, but he won the war because he had the Lord on his side. That’s just how I feel about this fight with Cassius Clay.

Judges 7 is one of those cheerfully brutal Biblical episodes in which the righteous smite their enemies. In this case, the Lord delivers the Midianites into the hands of Israel. He instructs Gideon to choose a conspicuously small army of men, no more than three hundred from among the thousands. So Gideon leads a crowd of men to the water, dismisses those who kneel down to drink and recruits only those who lap the water up with their tongues ‘as a dog lappeth’. These men are sent out against the enemy camp armed with trumpets and lamps inside pitchers, and in due course the Midianites are well and truly smitten. Their princes Oreb and Zeeb are slain and their heads cut off and brought to Gideon on the banks of the Jordan.

The Book of Judges is a cloudy lens, but if you squint through it what comes into focus is Frazier’s aversion to a man who had renounced Christianity for a ‘foreign religion’ and refused to fight in the Vietnam War.

The week before the fight, Frazier and Ali were on the cover of Time magazine under the headline ‘The $5,000,000 Fighters.’ The story, based on hours of interviews with both boxers, summed up the simple symbolism of the fight: Shrewd prefight publicity has turned the billing into Frazier the good citizen v. Ali the draft dodger, Frazier the white man’s champ v. Ali the great black hope, Frazier the quiet loner v. Ali the irrepressible loudmouth, Frazier the simple Bible-reading Baptist v. Ali the slogan-spouting Black Muslim.

On 8 March 1971, 20 000 people packed into Madison Square Garden to watch what turned out to be one of the most memorable heavy-weight boxing matches in history. The fight went the distance and all three judges scored it in favour of Frazier.

It’s the happiest day of my life, my father said. Except for the day I married your mother, the day she gave birth to your sister, and the day I bought my first car, a ’38 Chevy with a dickey seat. Jissie that was a beautiful car.

Branko

I’m a glorified taxi driver, Dad says. I should put a sign on the roof. It’s Saturday night and we’re fetching Sylvie from a session in the Skilpadsaal. Usually the hall is used for roller skating, but tonight there’s a band. When we dropped her earlier a boy in a pink shirt was leaning against a pillar smoking a cigarette and she said, He’s the bass guitarist.

And Dad said, Ag any mampara can play the bass guitar.

The streets around the showgrounds are full of cars but Dad finds a parking close to the hall. It’s just the two of us in the car. Mom’s at home with Joe.

Dad’s idea of being on time is to be half an hour early, so he’s always waiting, ready to be impatient when the time comes. Sylvie is always late, especially at the sessions. She’ll push her luck by fifteen or twenty minutes. So help me, Dad says, if you keep me waiting again I’ll come in there and drag you off the dance floor. She would die of embarrassment. But he’ll never do it. For one thing he’s wearing his pyjamas under the old houndstooth overcoat he bought with his first pay cheque. That was round about the time Moses fell off the bus. For another, Sylvie always gets her way.

Dad opens his window an inch so the glass won’t mist over and the music from the hall drifts in on the cold air. ‘Whiter Shade of Pale.’ They’ve started with the slow dances and that’s a bad sign in Dad’s book. He’s left the ignition key turned so his parking lights will show and some joker won’t ride into us. There’s a dim green light coming off the dash. We’re parked under a plane tree and the streetlight throws a lace of leaf-shadow over the bonnet. When cars come up behind us, long slow shadows creep over the cab. I shouldn’t fall asleep like a kid, but after a while my head gets heavy, and I breathe in the animal scent of the leather seat, which creaks every time Dad jogs his foot.

I must have dozed off because Sylvie is at the window. She’s ten minutes early and she’s got her friend Glenda in tow. Never mind the weather, they’re both wearing bolero tops. It’s an old trick: she wants to stay a bit longer and the friend is there to make it harder for Dad to say no. Dad man, she says, everybody’s still dancing. Who is this everybody? he says. I’d like to meet him. But he always says yes in the end. She’s his princess.

There are goosebumps on Glenda’s arms. Perhaps we’ll drop her at her house in Valhalla afterwards.

Dad complains about driving, but there’s nothing he’d rather do. On a Sunday, when we get back from church, he’ll say: I think it’s time to see if the fish are biting. This means we’re going to drive out to Harte-beespoort Dam or Bon Accord or maybe even all the way to Pienaars River or Loskop. Dad was a fisherman in his young days and the dams are his landmarks. The rest of us are bored with these places, we want to go to Bapsfontein or the Fountains, but Dad never tires of them. He likes to be near water, but not in it, watching people potter around in motorboats or cast a line. Mom doesn’t mind the drive because it gives her time to knit. On a round trip to Pienaars she can finish the whole front of a cardigan.

Bon Accord sounds grand but it’s just a sump of muddy water in a tangle of rutted roads and scrub. There’s no caravan park but campers carve out sites under the thorn trees to rig their tents. The whole place smells of mud and unhappy fish. We bump around on the tracks from one fishing spot to another. We’re looking for the bank where Dad and Uncle Arthur used to pitch a tent for the weekend before either of them was married.

Mom and Sylvie wait in the car while we go exploring. Dad walks off in one direction with his hands behind his back. There’s an angler sitting on a camping chair down there and he’ll strike up a conversation with him about rods and reels. Joe and I go the other way. We pick up old bait, stinking lumps of carp and mieliepap packed around rusty hooks, and we get our feet caught in tangles of blue-green line that look like the balls of hair Sylvie combs out of her brush and leaves on the edge of the bath.

When we get back there’s a commotion. Some clot in a Studebaker has got stuck in the mud reversing his boat trailer down to the water’s edge.

Dad insists we go to the rescue. I’m in my new running shoes with the red and blue stripes on the side and I want to take them off before I wade into the shallows, but Dad won’t let me. You’ll stand on a hook or something, he says. You’ll get lockjaw like Uncle Franjo. Now get in there and push.

They’re just a pair of tackies, Joe says. Everyone knows there’s a difference between tackies and running shoes. He’s wearing his old slip-slops.

The driver of the Studebaker revs the engine, the wheels spin and the car sinks deeper into the mud. Dad talks to him through the window. Then the man gets out, high-stepping to dry ground, and Dad gets behind the wheel, and he knows how to do something with the clutch, and with all of us pushing, the car and trailer come free. The driver applauds.

My shoes are covered with thick black mud. Joe rinses his slops off in the water, but there’s not much I can do.

We’ll touch them up with shoe white, Mom says. They’ll be good as new.

But they’re never the same again. Dad makes me put them in the boot so they don’t spoil the mats, even though he has extra mats on top of the standard ones to keep them clean. One day when he sells the Zephyr, one day soon, the mats will be in perfect nick.

Brainless bloody monkey, he says when we’re driving home, meaning the man who got stuck in the mud.

Why did we have to help him then? I ask.

He says nothing. So Mom says: That’s what you do. You help your neighbours and when you’re in trouble they help you back. You hope.

On the way we stop off in Sunnyside. Normally the rest of us go window-shopping for a block or two while Joe hunts around in the book exchanges, but I won’t get out of the car. I’m not going to walk around kaalvoet in town like a rock.

Joe

The Fight of the Century was promoted by a theatrical agent called Jerry Perenchio, who blithely told the world: I really don’t know the first thing about boxing.

Perenchio was an innovator. Even before the fight he had the idea of auctioning off the fighters’ shoes and gloves. If a movie studio can auction off Judy Garland’s red slippers ... these things ought to be worth something. You’ve got to throw away the book on this fight. This one transcends boxing—it’s a show business spectacular.

The purists were not pleased with the turn boxing had taken. They railed against the playacting, the vaudeville routines and costume changes, and their resentment just fuelled the fire. The circus was in town and there was no turning back. At the head of the parade, fitting the new style like a fist in a glove, was Muhammad Ali. He had been annoying the authorities for years: his showboating at the weigh-in for the first Liston fight had seen him removed from the venue and fined. But this seemed innocuous by comparison with the carnival atmosphere before the Frazier fight. Time magazine’s description of Ali’s retinue, published on the eve of the fight, captures it vividly: There is Bundini, the cornerman and personal mystic who calls him ‘the Blessing of the Planet’; a handler whose sole job is to comb Ali’s hair; assorted grim-faced Muslim operatives; imperturbable Angelo Dundee, his trainer since 1960; Norman Mailer; Actor Burt Lancaster; Cash Clay Sr. in red velvet bell-bottoms, red satin shirt and a plantation straw hat; the Major, a high roller from Philly who tools around in a Duesenberg; and Brother Rahaman Ali (formerly known as Rudolph Valentino Clay), his yeah-man. Ali had said before that white America was unsettled by the spectacle of black people with money to burn, by the men in mink coats and hats, the women in spangled gowns, the customized Cadillacs.

The sight of two men pummelling one another senseless for prize money must always have attracted the merely or morbidly curious, those with no understanding of the finer points and a taste for blood. But as the era of the mass media dawned and boxing became less like sport and more like entertainment, it found a new audience among people like me, the know-nothing fans who could hardly tell a hook from a jab.

While boxing in general did not appeal to me, my interest in Muhammad Ali was all-consuming. I might have forgotten the full extent of it, as we forget so much of what we thought and did in the past, had it not been for the archive of cuttings.

When my obsession faded away, I put the scrapbooks and loose cuttings in a cardboard box. In time, I moved out of my parents’ house and went to university, and I left the box behind in a cupboard. But the past is not so easily disposed of. I wanted to be a writer and the box came to seem like a key to my past. It was a journal written in code, the most complete record of my teenage life to which I had access, despite the fact that I was not mentioned in it once. I retrieved it from my parents’ house and carried it with me to a dozen homes of my own.

Over twenty years, I went through the scrapbooks so many times I lost track, intending to write something about them, intrigued anew by what they might reveal of the world I grew up in. A book eluded me. Why? I wasn’t sure what I was looking for: I didn’t know what questions to ask of these yellowed pages. Each pass through the archive produced some sketchy drafts of this chapter and that passage. It also produced pages and pages of notes and outlines, scattered associations and half-formed structures, summaries and quotations, all added to a lever-arch file, and then revised and annotated at each revisiting. Finally, this file stuffed with contradictory notes became as intractable an obstacle as the scrapbooks themselves, a shadow of obscure intent over the blank page on which a book might actually start.

Branko

We’ve been living in Clubview for five years. Before that we were renting in Pretoria West, but this house belongs to us. It’s in the ranch style, which means the bedrooms are all in a row and the garage is joined on next to the lounge. The plate-glass windows are nearly as big as a garage door. It’s like we’ve moved to America.

One wall of each bedroom in the house is covered in wallpaper. If it’s just one wall it makes the place look modern, don’t ask me why. Sylvie’s room has scenes from the Ming dynasty. You can see pilgrims making their way through the landscape, which is the colour of tea, or resting under frilly trees and pagodas. In the room I share with Joe the paper is a sky-blue backdrop for hot-air balloons, paddle steamers and Bugattis. It’s like a page out of Jules Verne. The wall behind the fireplace in the lounge is papered to look like knotty pine. The mantelpiece is made of real slate.

An oil heater stands on the hearth like a lunar module. Dad doesn’t believe in open fires: apart from being a fire hazard, he hates the smell of coal smoke and soot. He likes things to have more than one purpose. That’s why he brought home the side-table-cum-lamp (as he calls it) with a green Formica tabletop and two pendant lights with orange plastic shades.

The homework has been done and the dishes have been washed. Dad is relaxing in the armchair next to the radiogram, with his legs stretched out and his head cocked towards the speaker. No one else ever sits in Dad’s chair. We’re as attached to our chairs as the chairs are to their places in the lounge: their legs have made little hollows in the pile of the carpet and so they must occupy that spot for ever. Dad is reading the Pretoria News. Before supper he read as far as the editorial; now he’s busy with the sports pages and the classifieds.

Some joker in Villieria is selling a Sprite 400, he says.

Mom ignores him. She’s supposed to ask what he wants for it. Only wants seven hundred rand for it, he says regardless.

Nothing escapes him. If some joker in Villieria has a caravan for sale, if Harlequins beat CBC Old Boys 2-1 in the Sunday hockey league, if the Russians are threatening to put a man on the moon—bloody Russkis, that’ll be the day—he knows about it.

The devil finds work for idle hands and so Mom’s are always busy. Every summer she knits each of us a jersey for the coming winter. She crochets baby clothes, bootees, matinée jackets, bedspreads, runners, doilies. She knits cardigans and pullovers for the rest of the family on order and presents them to the buyers wrapped in cellophane as if they came from Garlicks.

This evening she’s cutting out a top for Sylvie. She kneels on the carpet with the material and the tracing-paper pattern that’s pinned to it spread flat. It’s always better to do your cutting on the floor, she says. She makes a lot of my sister’s clothes, so she can keep up with the latest fashions without breaking the bank (as Dad puts it). We’ve had tent dresses and granny-print pinafores. Now it’s bolero tops. Joe’s been saying the word all evening as if he’s learning another language. Bolero, bolero, bolero. When he gets like this I want to hit him.

Dad puts down the News and picks up the Reader’s Digest. There’s a red silk poppy sticking out of it like a tongue. The Digest comes every month and the volume of Condensed Books every second month. It’s a racket, he says. They send them whether you want them or not and then you have to pay for them. He piles the books on the floor next to his bed, and the pile never grows because whenever he puts a volume on top, Joe takes one from the bottom.

For your edification and your delight /

our headline’s the deadline on Thursday night.

Turn that up, Dad says, the news is about to start, but Joe pretends that he can’t hear. He’s at the dining-room table, squeezed into the narrow space between the wall and the tabletop, with a big drawing book and a pile of Koki pens. He’s making the first Ali scrapbook. I go and turn up the radio.

Mom picks three pins from between her lips like fishbones and stabs them into the pincushion. What’s happened to my scissors? She starts unpacking her knitting bag. That green thing is the front of my winter jersey. I wish she’d ask. They’ll have to kill me first. That fat stack of cuttings in a bulldog clip is crossword puzzles. And that black notebook is where she writes down the LM Hit Parade every Sunday so we can see which songs are on the way up or down and take bets on what will be number one. And those things are rabbits. She’s knitting them for the school fête and each one has a different jersey.

Jissimpie, Pats, Dad says. Are they multiplying in there?

That’s not funny Bo. Anyone seen my scissors?

Joe is using the sewing scissors to cut an article out of the paper. That won’t be funny either when Mom finds out. The sewing scissors are meant for nothing but silk and satin. They’re supposed to fall through chiffon like a hot knife through butter. We’re strictly forbidden to use them on our school projects. But Joe always gets away with murder.

It’s half past nine—way past your bedtime, Dad says—before Sylvie tries on the bolero and then it’s just a waistcoat.

Ivan Vladislavic was born in Pretoria in 1957 and lives in Johannesburg. His books include the novels The Restless Supermarket, The Exploded View and Double Negative, and the story collections 101 Detectives and Flashback Hotel. In 2006, he published Portrait with Keys, a sequence of documentary texts on Johannesburg. He has edited books on architecture and art, and sometimes works with artists and photographers. TJ/Double Negative, a joint project with photographer David Goldblatt, received the 2011 Kraszna-Krausz Award for best photography book. His work has also won the Sunday Times Fiction Prize, the Alan Paton Award, and Yale University’s Windham-Campbell Prize for fiction. He is a distinguished professor in creative writing at the University of the Witwatersrand.