SALOMÉ,

A WEDDING NIGHT FOR ZEN

ZEN & MUSHROOMS

Mariam BAZEED,

THE MOST EXPENSIVE MUSHROOM

TWO CUTS

OF LOVE & LUST

ANONYMOUS,

YOU DON’T SATISFY

Translated by Abdullah al-UDHARI

& TWO PIECES

OF VERSE

THE MOST EXPENSIVE MUSHROOM

YOU DON’T SATISFY

Translated by Abdullah al-UDHARI

Ulayya bint al-MAHDI,

EPIGRAM

Translated by Yasmine SEALE

EPIGRAM

Translated by Yasmine SEALE

Edited by Selma DABBAGH, WE WROTE IN SYMBOLS (SAQI Books) is an anthology of writing by Arab women on lust, love and the erotic. It is a little-known secret that Arabic literature has a long tradition of erotic writing. Behind that secret lies another—that many of the writers are women. Accross 320 pages, and spanning 3000 years, WE WROTE IN SYMBOLS is a substantial elucidation of such a secret, and sits works by classical authors, award-winning and contemporary writers and translators side-by-side (including Hanan al-SHAYKH, Hoda BARAKAT, Joumana HADDAD, Ahdaf SOUEIF, Leïla SLIMANI, Isabella HAMMAD and Sabrina MAHFOUZ, amongst others). Here, a wedding night takes an unexpected turn beneath a canopy of stars; a woman on the run meets her match in a reckless encounter at Dubai Airport; and a carnal awakening occurs in a Palestinian refugee camp. From a masked rendezvous in a circus, to meetings in underground bars and unmade beds, there is no such thing as a typical sexual encounter, as this electrifying anthology shows.

Buy the book direct from the publisher here, and see below for FOUR excerpts from the collection; SALOMÉ’s A WEDDING NIGHT FOR ZEN, Mariam BAZEED’s THE MOST EXPENSIVE MUSHROOM (both written down and read aloud), the ANONYMOUS poem YOU DON’T SATISFY (translated from the Arabic by Abdullah al-UDHARI) and Ulayya bint al-MAHDI’s EPIGRAM (translated from the Arabic by Yasmine SEALE) ...

Buy the book direct from the publisher here, and see below for FOUR excerpts from the collection; SALOMÉ’s A WEDDING NIGHT FOR ZEN, Mariam BAZEED’s THE MOST EXPENSIVE MUSHROOM (both written down and read aloud), the ANONYMOUS poem YOU DON’T SATISFY (translated from the Arabic by Abdullah al-UDHARI) and Ulayya bint al-MAHDI’s EPIGRAM (translated from the Arabic by Yasmine SEALE) ...

SALOMÉ

A WEDDING

NIGHT

FOR ZEN

Breakfast the morning after the wedding was in the largest house in the row that ran along the side of the hill. Coffee had been set up in the conservatory, where moss grew around the kilim, and crayons were stamped into the floorboards like sealing wax. Zen had left her new husband alone in their tent and entered the house with a book in her pocket, in search of a bathroom and a place where she could sit and read and wouldn’t be expected to introduce herself all over again. Only the newlyweds had slept in a hotel—the rest of the guests had camped on a sloping field with the smell of cow dung, joints and burnt sausages.

Zen and her husband had taken a day off to make a mini break of their weekend away for the Friday evening wedding. Zen had insisted on a trip to an exhibition of Japanese erotic art on the Friday morning, before they drove down. In the car, her husband, who had been unswervingly antipathic towards the exhibition, made conversation in the form of sharing gossip about the other wedding guests. There were two brothers and a woman she should look out for in particular, he told her. The woman had been married to the younger brother before she divorced him and married his older brother. The wedding was the first time the brothers were to meet since. Zen could see the scandal in that, but could not find it in herself, not for all the tea in China, or dual carriageways in Britain, to ask her husband why the exhibition had been such a source of annoyance to him.

The wedding invitation came from Zen’s husband’s university friends. The weekend of the wedding, a group of them had, he told her, bought weed from a mature student who grew it under a leaded roof in a west country valley. The roofing was apparently impermeable to the police helicopters’ heat monitoring equipment and preserved the integrity of these essential hydroponic skunk farms. On the first night, the Friday, there had been a lot of talk about how to confound, thwart and get around policing among the guests. Zen watched the wife of the two brothers glide around the party; her beauty hoisted high on her cheekbones.

Zen and her new husband were the only guests who lived in the city, though the wedding crowd came from no one place, for the groom was from Isfahan, and the bride was a descendant of Suffolk clergy. The hosts had also welcomed gypsies from the valley who’d arrived with their instruments, silver teeth and wide-brimmed hats. With the exception of the gypsies, who seemed to already know Zen better than she knew herself, the guests had been intrusively friendly and by midnight, Zen hadn’t another engaging word to offer them. She had given herself up to alcohol and weed supplied by her husband’s friends who had, by then, become less inquisitive. After the July sun that had engorged the marquee with a vast horizontal light sunk away into the valley, they’d been left with the light of torches stabbed into the ground by the tent pegs. The lighting had contorted the guests into eerie shapes with ethereal eyes.

Zen had not expected to recognise anyone in the morning.

For Saturday night, the day after the wedding, the bride and groom had a follow-up party planned. But first, breakfast in the conservatory was to be followed by a tour of the local burial grounds, which lay like nodes across the countryside’s ley lines pulsating positive vibes into the local inhabitants, according to more than one of the guests Zen had been embraced by the previous evening.

Zen’s chosen book, which she held in front of her face to avoid making contact with the other campers who were now shuffling in for bread and eggs, was Franz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth. She found herself reading the same sentence over and over again, getting no closer to realising the author’s meaning and unable to make her own interpretation of what was written. The book had the desired effect on those guests who had heard of the author.There were nods of recognition, but the title was daunting enough, thankfully, to prevent anyone from engaging further with her on its content.

The younger brother, whose wife had left him with the style and treachery befitting a Greek goddess for his older sibling, had brought a new girlfriend with him for the wedding.The night before, Zen’s husband had shown unusual interest in her and her dress, which clung to her body like fish scales and winked confused, solitary signals from dusk onwards. Sexy, he’d told the younger brother, who stooped over a tankard and let his hair touch at the high bump in his nose. His older brother had small, bite-sized tattoos running along his inner arms and walked with his legs placed apart, as though preparing to lift an object of some weight. When Zen’s husband said sexy, the younger brother had looked at his girlfriend, who seemed to Zen more of a formula for a girlfriend than a person with any individual characteristics or atypical behaviours of her own.The girlfriend’s body could not have been more different from Zen’s; she flattened where Zen swelled, and grew to heights that Zen would never know. Really sexy, Zen’s husband had said with approval, chuckling as though Zen wasn’t there. The girlfriend emptied the space around her when she moved on the dance floor and Zen couldn’t tell whether this was because she made the other dancers feel dumpy, or out of embarrassment, because she moved like her limbs were held onto her body by pins.

‘Appearances are only one part of it,’ the younger brother replied, avoiding the beckoning motions of his girlfriend to come join her on the dancefloor.

‘I’m sure,’ Zen’s husband said. The connoisseur, thought Zen.

‘Rarely up for it,’ the younger brother looked towards the yurts on the edge of the forest before settling back on Zen’s husband, who took it as an opportunity to flaunt his stuff.

‘Oh, she’s always up for it, my wife,’ Zen’s husband said, now remembering introductions.‘Zen, have you met?’

‘Cool name,’ said the younger brother.

‘Short for Zenobia, not the Buddhists’ Zen. Zenobia was the Queen of Palmyra—’ Zen started, trying to inject new emotion into an old line, but she was thrown by the eyes behind the younger brother’s fringe; they had the stare of refugee children, who can tell you with one look that you will never know what they have known. The younger brother cut her off by examining her neckline, causing Zen to lift her glass to her mouth, her eyes picking up his, before he looked away at the dance floor, now also empty of his girlfriend.

Zen returned to their tent before her husband on that first night. He’d blundered his way back later, stoned, telling her about the opium the uncles had smuggled through customs. Zen watched him zip a sleeping bag around his fully-clothed body, complaining about the thinness of the ground mattress and the pains in his stomach. He’d removed an arm only to tap Zen’s arse to tell her they were getting him on stage with a microphone the next night, if she would believe that, before he passed out. Zen had turned off her torch and lay still, her body trying to settle into the English country earth, listening out for the Biblical lowing of cattle in the valley. A light had come on in the neighbouring tent and she could make out the movement of the older brother and his gliding wife in their tent next-door, streaks of limbs silhouetted against the thin fabric, entwined shadows reaching up to the stars. Zen heard their supressed laughter; their orgasmic pulses rocking the earth. Even the movement of nylon sleeping bags under bare bodies could be made out, a grunt followed by a sharp, distinctive gasp, the groan of male satisfaction, the murmurs of praise followed by the cooing congratulations of love. Zen couldn’t believe how it was that a woman could come so fast, for it had sounded immediate, but genuine. Not for the first time she wondered whether there was an anatomical glitch in her body’s wiring.

To make herself sleep, Zen put her hand between her legs and thought of the Japanese Shungo painting of the young wife being awoken by a man with a penis that, like all Shungo penises, was as thick as the trunk of a birch tree and headed by a slit concave cap.The elderly husband with his neat moustache sleeps on his back as the young wife opens her legs to this engorged limb, protruding from the groin of the young male intruder. In that moment the dimensions of the Shungo penis no longer felt like a joke, but an absolute necessity to Zen.

As the breakfast crowd continued to file into the conservatory, Zen curled up on her seat in the porch, trying to absorb wisdom from the printed page.An unhealthy-sounding car pulled up by the house, and footprints crunched across the gravel. Zen looked up as the door opened and the younger brother entered, his face and jacket shining with drizzle, his hair hanging in straight, wet bands down his face. Zen didn’t smile. Neither did he. If it were anyone else, she would have assumed that they didn’t remember who she was, but it wasn’t that kind of look. He disappeared next door, into the room with the fire, which the uncles had come in to from their yurts to congregate around, build, and feed from. The younger brother had been taken in by the uncles the day before. Along with a couple of the other guests, he was in the yurt-rental business and had helped the uncles construct theirs. From her seat, Zen heard the uncles clapping their leathered arms around the younger brother’s leathered body, asking him where he’d been. Zen heard him say ‘station’ and the name of the girlfriend. Still staring at the page, she recalled the sound of fractious voices and tears from the girlfriend of the younger brother late in the night; extracting words from the dreamworld of the night before to piece together a narrative of rupture. Better, said one of the uncles who gave a purr with the front of his tongue at the end of his words. She was too, too—and then a discussion for the right word amongst themselves—stiff for you. Better, you will find another.

The rest of the day—the walk to the ancient stones, the walk back, vegan hotdogs, cold tea—happened to Zen, but the memories of all that was flat, like photographs someone else has shown her. But even years later, Zen was acutely aware of how she’d felt later that day, in her body as well as her mind, when she was getting ready for the party, her hand shaking as she held the mascara brush to her lashes, whilst trying to stop misting the mirror propped against her bag. She recalled leaving their tent, drinking whisky from a silver flask passed to her by a man with a red cotton string tied around his neck, dancing with the same man, his leg catching between hers, his arm around her like a crowbar. Her hair, wettened by the summer showers, her head in a frenzy, the man pulling her in all directions across the dancefloor.

Then looking for her husband,trying to ensure that her dance partner did not take her for the wrong kind of amusement, Zen had wandered off and found a yurt perched above a clearing. Half of its flaps were rolled up, leaving those inside free to gaze out over the split hills.The uncles sat in a semi-circle around a stove. Zen later imagined the men wearing black eyeliner and red leather slippers, although she knew this was not the case, it was the way she wanted to remember the evening.They watched her as she entered and asked the stooped figure of the man who had not yet looked up about Zen. Zenobia the younger brother said. She’s named after a queen. The uncles liked this.They passed a small bong between them. One inhaled, and looked at Zen with inflated eyeballs, nodding his head.When he let out a breath, he indicated a cushion, ‘for the queen.’

The uncles watched her like a potential sister, wife, whore. They wanted more information. ‘Mo’ the younger brother said, using the abbreviation of his name that Zen’s husband liked to use among this crowd, ‘She’s Mo’s wife.’ The eyebrows rose, the eyes slid, the mouths paused. They didn’t seem willing to accept this.The younger brother gave the name of the state boundaries that Zen and Mo’s parents came from, which appeased the men to a degree. Then a joke that was not in a language Zen understood, but she had to look down anyway, for she was sure that they were laughing at what even strangers could see about her and her husband at a glance. The younger brother passed Zen the flask and she pulled at its smoke.

There was a scratching from outside. A microphone was being set up on a stage.Then the voice of the host announcing the band, talking about Mo—a good time kind of a guy. Zen excused herself from the yurt and its men. Outside she found the evening strangely bright; the sun setting in the valley caused stark flames of dying light to tear at the darkness, as though a fire was coming from the belly of Zoroaster himself.

She waited as minutes passed with Mo and the band still mucking around on the stage. The crowd was getting restless. They were a bunch who knew what to expect from musicians. Leaning against an outer tent post, Zen knew she did not want to be there watching her husband and she also knew that he wouldn’t really care whether she did or not. She was trying to decide which realisation was sadder, when, instead of retreating back to her tent, a hand took hers and led her away from the lights, down a path towards a semi-lit yurt at the far edge of the field.

The yurt has a door. The younger brother steps out of his unlaced boots and Zen too, without a glance or a word, takes off her sandals, now pasted with blades of grass. He ushers her into a space where a fire in a bulbous pot casts shadows and throws heat onto the sides of the tent and across the sheepskin-covered floors. He allows her time to take in the domed space, but not enough to reflect on why they’re there. She doesn’t want to think, either. He pulls up her skirt with his hands, spreads them wide to cover her buttocks with his palms, and tugs off her panties. Having only washed herself in a basin she flinches at the thought of her odour, but his head is already bent beneath her. She catches her balance against a post of the low bed, her dress is now unbuttoned, her breasts pulled out of the bra cups encasing them. The bottom of her skirt is around her waist and he’s sucking her into him through his mouth, breathing the sweat around her crevices and her armpits, squeezing her nipples between his fingers.

An opiated blur has invaded Zen’s body. Her head is disconnected, her nipples are raw nerve endings and feel as though they’ve been turned inside out. Her pulse lies firmly between her legs. The sight of the younger brother’s profile angled against her breasts makes her widen her legs under him, she watches him stand as she pulls at his belt and undoes the buckle with quick fingers. He puts his hands in her hair and thrusts himself towards her face. Her dress is ruched around her middle, pulled down from her chest. Zen later remembers crawling to get high enough to take him in her mouth. She only just tastes him when he indicates that he doesn’t want more of that. He gets her to lean forward on the bed, his hands moving up and down her, his fingers pushing her cheeks apart, plunging into the source of her. She pulls a cushion under her raising herself to him as she hears from afar the opening bars of a guitar with lines sung too close to the mic. A cheer from the audience and she’s so scared that the younger brother will stop, that he won’t enter her, that she begs him to go on and he laughs a bit at her determination as he nudges against her untouched lips, before he enters, waiting for the drummer to crash on, so that the band’s noise will hide their own.

Zenobia and Mahmoud leave early the next day to avoid Sunday traffic. At the slip road onto the motorway, she reflects on the second time when she came on top and he took her breasts in his hands, before pulling her down so he could bite them. She is certain that fragments of the explosion that came out of her are still lodged in her innards. The couple listen to the news on the radio as they move into the fast lane. Mahmoud gives commentary which she mainly agrees with, but he concedes on one point that she argues on the basis of a recent article she’s read. On the Oxford bypass she thinks of the younger brother’s mouth buried in her.

Zen wonders whether by the middle of the week the throbbing will stop. That doesn’t happen, but both Zenobia and Mahmoud do go on to be most successful in their respective professions and good companions throughout the rest of their lives.

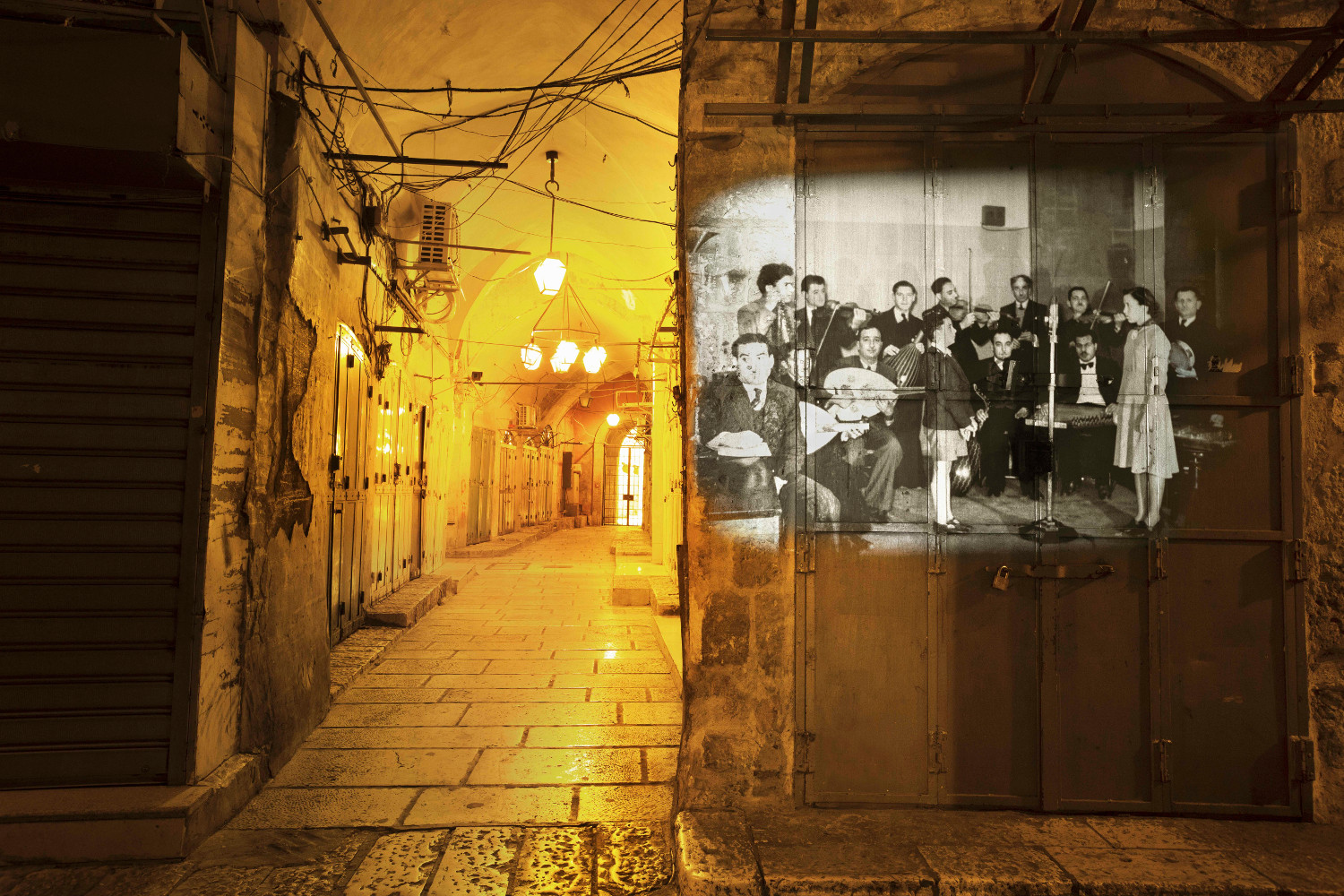

Rula HALAWANI

From the series, JERUSALEM CALLING (2015)

From the series, JERUSALEM CALLING (2015)

MARIAM BAZEED

the most expensive mushroom

My girlfriend she says

you smell like jasmine

holding my lips apart,

face propped up between my legs

breathing me in

like

I am some Provence postcard

purple lavender running

all along my snatch.

My girlfriend she says

you taste like truffles

her tongue on my tongue

lips on my lips

stealing breath straight

from my lungs.

and I do my best

to be the most expensive

mushroom

I know how to be.

My girlfriend she says you are so beautiful grabbing of me fistfuls

in her fists

to put in her pocket for later.

My girlfriend she fucks me

so it hurts

and I don’t even have to ask.

My girlfriend she sees me with eyes

blinded by a magic

I did not know I possessed.

I think, probably I have it out on some loan

whose terms I’ve forgotten

whose paperwork I’ve lost

whose principle and interest rates

I couldn’t tell you anything about.

Best, maybe, not to find out.

My girlfriend she eats me

like I am a Ramadan feast

on the 27th night. a Table of the Merciful,

laden: lamb, saffron rice, every raisin plump.

kibbe, sumac and Spanish pignolia blessed

in the gaps between her teeth.

And tamarind,

like fasting in the summer,

sticky, moving slow, sour-sweet.

My girlfriend she eats me

then spits me out

prune pits apricot bits crunching seeds of fig

from the river of khoshaaf

running

between my legs.

Maybe you think my girlfriend

says fucks sees eats

like a pretty metaphor

or like a scene in one of those butter-coloured movies

all panting,

muted bronze glowing sex—

nary ever a condom in sight.

No.

She fucks me

like that dog you saw one time

or like that monkey in the zoo

a different one time

baring its canines

unabashed in glee.

and I find strands of her

long bronze hair in the crack of my ass later on.

What I mean to say is,

there is no poetry in it—

only her hunger

which I will one day

chew up

swallow

digest

deserve.

† this poem is inspired

by Ella BOUREAU

whose eyes are open

& who’s taught me to see

by Ella BOUREAU

whose eyes are open

& who’s taught me to see

†

‡

ANONYMOUS

YOU DON’T

SATISFY

Translated from the Arabic

by Abdullah al-UDHARI

You don’t satisfy a girl with presents and flirting, unless knees

bang agains knees and his locks into hers with a flushing thrust.

‡ From the pre-Islamic, JAHALIYYA period

(4000 BCE—622 CE)

Ulayya bint al-MAHDI

EPIGRAM

Translated from the Arabic

by Yasmine SEALE

by Yasmine SEALE

To love two people is to have it

coming: body nailed to beams,

dismemberment.

But loving one is like observing

religion.

I held out until fever

broke me.

How long can grass

brave fire?

If I did not have hope

that my heart’s master’s

heart might bend to mine,

I would be stranded, no

closer to gate than home.

In order of appearance—

Selma DABBAGH is a British Palestinian writer whose debut novel Out of It (Bloomsbury) was a Guardian Book of the Year. Her fiction has been published in Granta and Wasafiri and translated into a number of languages including Arabic, Mandarin, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian and French. DABBAGH has also worked on film scripts and as a writer for feature films and radio plays and her BBC R4 play The Brick was nominated for the Imison Award. She is the editor of We Wrote in Symbols.

SALOMÉ is a pseudonym of a published author.

Mariam BAZEED [they/them] are a non-binary Egyptian immigrant, writer, performer and cook, living in New York. BAZEED received an MFA in Fiction from Hunter College in 2018 and is currently at work on their second play, faggy faafi Cairo Boy; and, with poet Kamelya OMAYMA YOUSSEF, on Kilo Batra: In Death More Radiant (a working title). BAZEED curates and runs a monthly(ish) world music salon and open mic in Brooklyn and is a slow student of Arabic music.

Abdullah al-UDHARI was born in Taiz, Yemen, in 1941. He studied classical Arab literature and Sabaean epigraphy at London University, where he also received a doctorate for his pioneering study, Jahili Poetry before Imru al-Qais [4000 BCE–500 CE], which established him as an authority on early Jahili literature. In 1974 he founded and edited TR, an Anglo-Arab literary and arts magazine. He is a literary historian, poet and storyteller, editor of Classical Poems by Arab Women (Saqi Books), and author of Voice Without Passport, The Arab Creation Myth, Victims of a Map and Modern Poetry of the Arab World.

Yasmine SEALE is a British-Syrian writer. Her essays, poetry, visual art, and translations from Arabic and French have appeared in many places including Harper’s, the Times Literary Supplement, Apollo and Poetry Review. She was the winner of the 2020 Queen Mary Wasafiri New Writing Prize for poetry. She is the author of Aladdin: A New Translation (W. W. Norton, 2018) and, with Robin MOGER, of Agitated Air: Poems after Ibn Arabi, forthcoming from Tenement Press. She is working on a new translation of One Thousand and One Nights for W. W. Norton.

IMAGE—

© Rula HALAWANI, 2015