SURREALISTS

at the END of the WORLD

at the END of the WORLD

Roisin DUNNET

Every day before dawn, they would walk in darkness to the port to see if there was a boat. There rarely was, and none so far had accepted them as passengers.

Despite this, Jacqueline and Lola came to enjoy the walk, the deserted streets, the rare time alone. The port town had become a dangerous place but in that hanging hour, before darkness finally receded, the residents laid down their arms. The drinkers were unconscious, the rapists in retreat. The homeless children, the sight of whom distressed Jacqueline so much, were out of sight, curled round each other in shadowy doorways. The lights of nearby cities were kept out, so the stars shone brighter than they’d used to in Paris.

Jaqueline and her husband Pierre were staying with their children in the house of a wealthy aunt, who had already made her way off the continent. It was in her interest that they stay as, without them, there would be no one to prevent the place from being looted. As a matter of fact Peirre hated his wife’s aunt Marie, and Marie, with equal vehemence, hated him. Jacqueline couldn’t give a shit what they thought of each other. She knew her aunt hated Pierre out of loyalty, because Pierre was a Philanderer. Jacqueline, who usually tried to ignore this fact about her husband, was pained by Marie loathing him so unreservedly on her account. She also wished her aunt had tried to endear herself to Pierre at least a little more because then she, Jacqueline, would be spared having to hear him call her an ‘old bitch’ all the time. Anyway it was good, in this situation, to have an aunt, and to have this house with no aunt in it.

They had invited Lola to stay with them, as well as Antonio and his wife, and Fernan. Fernan had bought his lover Irena with him without asking, but Jacqueline did like her. Fernan rarely asked permission for anything, yet he never seemed to offend anyone, except sometimes when he was really drunk. Three more artists, Alf, Andre and Alex, were staying in a boarding house nearby. They all knew each other from Paris, and the house was large, so inevitably they all ended up congregating in Aunt Marie’s house, trying desperately to entertain each other and distract themselves from the very imminent war. They made eight, two rows of four squares, if you included some but not all of the women.

It wasn’t easy for anyone. Fernan seemed to be bearing up best, he had a quiet fortitude unusual in his circle. Alf was the oldest and had seen war before, which made him more afraid, but more able to bear his fear. Everyone else did what they could to stay sane, waiting together at the port at the end of the world.

Antonio, who had known poverty, and came from it, knew better than to expect life to be good to him and its luxuries plentiful. But he had become wealthy and well known. He had been accepted into polite society, had sat at the tables of politicians and been present at the writing of great manifestos. He had a beautiful and accomplished wife of a better background than his own, together they ate expensive meals. Now it seemed possible it would all melt away again, like sugar floss under a flame. The stink of the sea reminded him of his childhood, his island home, his dead grandmother. Lola held his hand one evening while he cried unreservedly on the porch. His wife couldn’t deal with him any more. Jacqueline and Pierre’s children were in bed, this was when their bedtimes were still being maintained. The homeless kids gathered and watched from the shadows. Lola smoked cigarette after cigarette, showing patience that surprised Jacqueline, and said ‘There, there love,’ from time to time.

Lola was the only one seemingly without fear. Jacqueline was glad to have her here with them: Lola was not always easy to deal with, but in a situation like this she was perfect. The fear and malaise that presided over them could only be dispersed by Lola’s mania. Her last husband had been one of the most famous artists in the world, and when they broke apart she had a very public (in their world at least) breakdown. But she could deal with living on your nerves, as Jacqueline could not. Jaqueline got thin and bloated, went ashy with stress and bad diet. Lola wore a dress of incredible yellow, got a tam, her hair curled more wildly, her eyes got larger and more liquid. She’d always been attractive in an indefinable way that you could chose to adore or resent but now, in the twilight of their country’s most recent peace, she became frankly beautiful. Lola and Jaqueline had known each other, one way or another, since they were children themselves. They lost touch after Lola ran away from finishing school, but then Jacqueline turned out to be not quite so boring after all, married Pierre who was an artist like Lola. Pierre thought Lola was brilliant, and had actually tried to fuck her, but Jaqueline and Lola’s husband had foreseen this and conspired to prevent it. Whether Lola, given the choice, would have fucked Pierre is not certain, but she had been devoted to her husband. Utterly devoted, and then he went off with much younger woman, a fashion model.

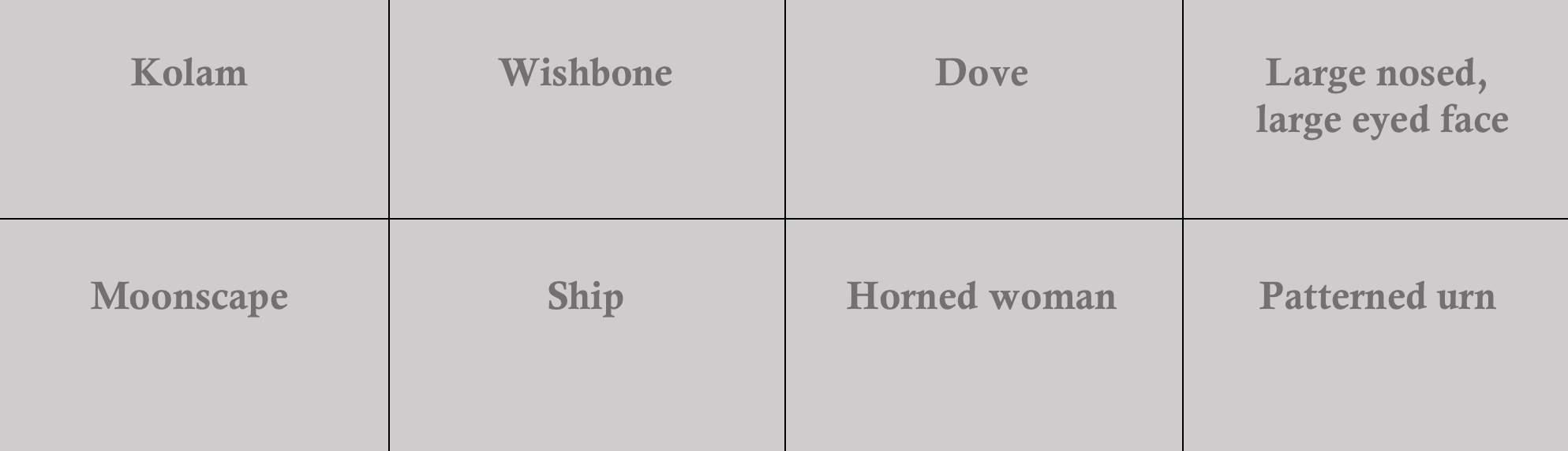

Only in Lola’s presence did the children stop whining with boredom. Only Lola had the energy to invest in teaching them to entertain themselves they drew in the dirt of the road, they collected petals from the flowers in neighbourhood gardens to make Kolams on the ground. She told them how, when she travelled to south India, she had seen them outside the doors of houses, made by women at dawn with lines of rice flour. She had not wanted to ask how it was done, she couldn’t say why, so she watched and watched and found out by stealth how they were made, guiding a fine stream of flour with the edge of a thumb.

‘So I tried some myself, on my bedroom floor. I never got any good at it. But some women,’ she told the children, ‘Can draw the most intricate designs, perfectly symmetrical, and make not a single mistake.’

Lacking rice flour, she showed the children how to trace these patterns in chalk and sugar water to make ants come to them, form the lines with their wriggling mass of bodies. Celine, Jacqueline’s daughter, took to the work immediately and would spend hours running her finger in the dirt as the sun made its listless way across the sky. Her brother Thomas got fed up more quickly, and so Lola found him a ball, a faded dog-chewed one, and threw it for him to catch or hit with a stick again and again. At first all the men had been keen to play with him, but finally even patient Fernan had grown exhausted by the game. Thomas wouldn’t get bored with the ball being thrown if you did it a thousand times, whenever you wanted to stop was always to soon. It was Lola who, despite her restlessness, lasted longest. But eventually even she got tired saying ‘Thomas, I’ve thrown your fucking ball, now get your aunt Lola a fucking drink and a cigarette. That’s the deal.’ Thomas accepted this.

Though drinks and cigarettes were scarce there usually were some. ‘God knows what we’ll do if they run out completely’ said Alf, who had started a secret stockpile just in case.

All of them gathered every evening and most of the day in the poorly lit drawing room at the aunt’s house. There was very little to do, buy or see in the town. Sometimes there would be news, rarely good. Occasionally someone from the capital who, because of privilege or foolishness had opted to remain there, would send a letter that still contained the old gossip and drama, productions in which those assembled in the drawing room no longer played their parts.

Jaqueline did not wish to discuss the current situation, and especially not at dinner, but the men, mostly, did. Fernan’s lover, the implacable Irena, would sometimes join the conversation with strident observations. Sometimes though she seemed as sick of the whole goddamn show as Jaqueline and the two would talk together of art or places in Europe they had both been, or Irena’s research. She was a scientist, which seemed impossible. She wore white shirts and belted trousers, hair in a dark braid. Her curves were fascinating, sumptuous in a way that Jaqueline thought at odds with her practical nature.

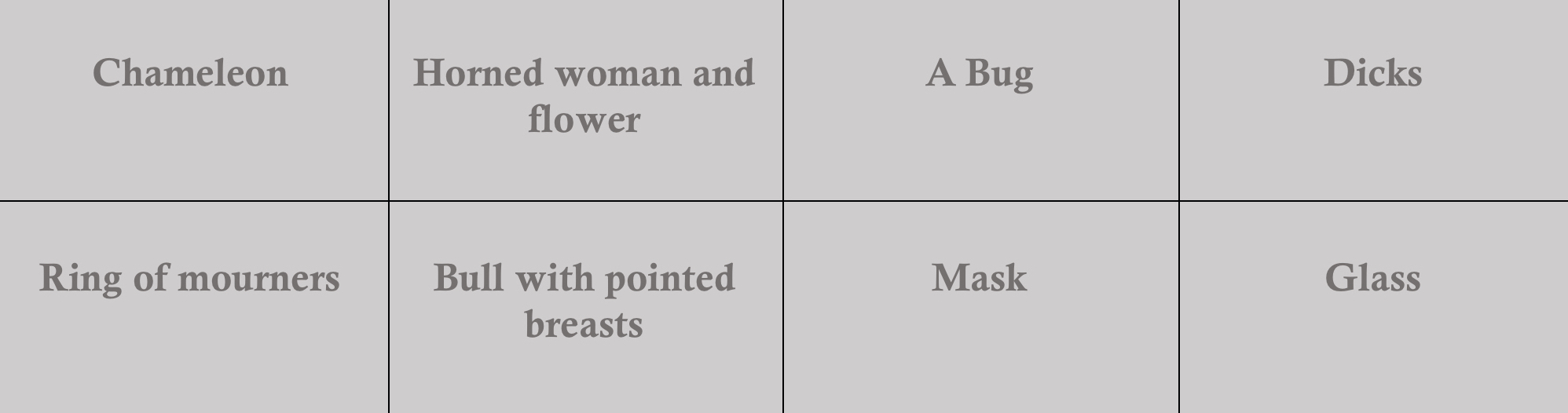

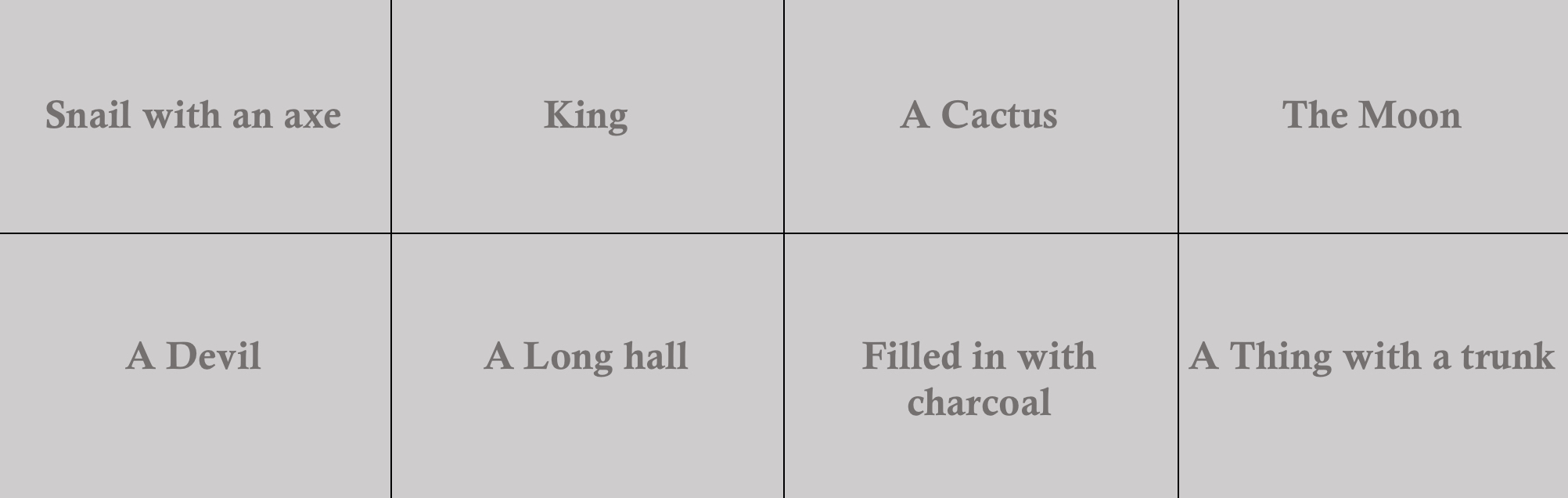

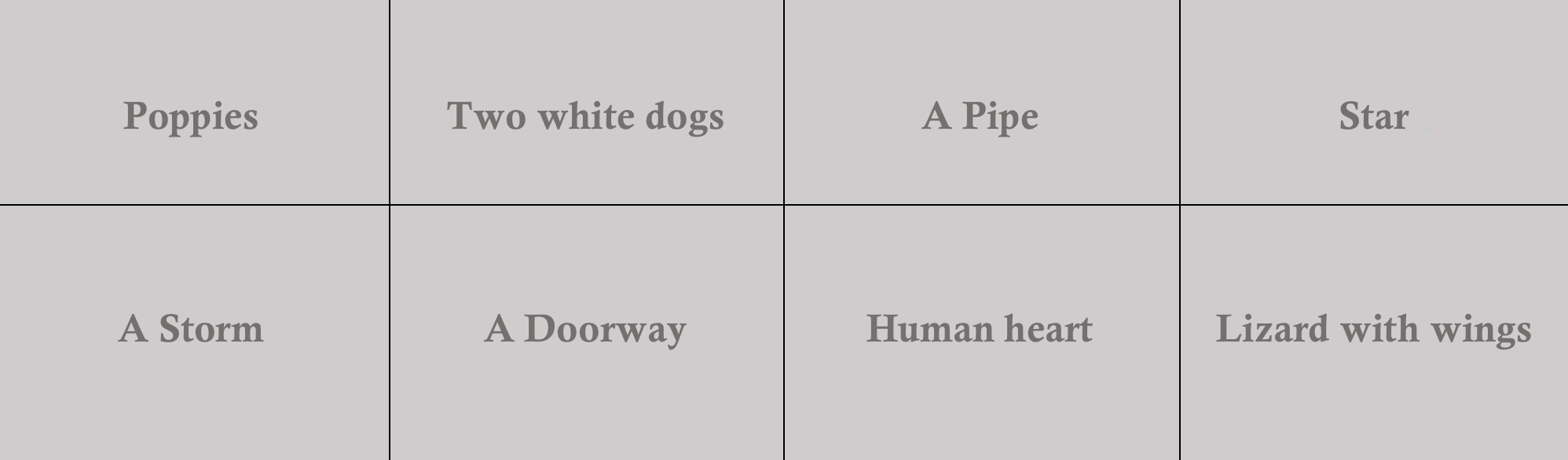

Usually it was after dinner, when the plates had been cleared away (one of the aunt’s servants, a maid who also cooked for them all, and shopped for food each day) and they had each had a little to drink, that the artists and Irena made the drawings. It was a simple idea. They divided a piece of paper into eight squares. Then, using coloured pencil, or watercolor, even a piece of burnt cork or twig if they could handle the material gracefully, each of the artists, some of them the most famous practising in the world at that time, filled in a square. It was a very practical way of passing the time, costing nobody anything. The only problem with it as an occupation was that, apart from Irena, the participants were competitive, and took a long time over the pictures. As they could only work on the small images one at a time, the project would sometimes take hours. Those who did not participate, Jaqueline and Antonio’s wife Elaine and Alex’s wife Irma, (the poet) were called upon to look and, implicitly, to judge the best. The children were usually in bed although Celine, as the older, would sometimes demand to stay up later than Thomas and watch the whole performance, eyes drooping with tiredness, but always fixed upon whoever was screwed up tightly over the piece of paper. Jacqueline watched the artists too, observing who imposed their will upon the paper, who seemed to draw the work out of the creamy surface, who laboured in pain, and who was lightened by the process. The drawings were usually done in candlelight, although one or two were made in the horrible dregs of dawn.

They all felt their distance from Paris keenly, their normal lives in which they were busy and important, surrounded by their belongings. Pierre missed his dogs terribly, they had been left behind at the town-house in the care of the maid.

‘Our two White Wolves.’ was what he called the huskies, and he recollected them tearfully at dinner: ‘Such big animals, but they are so gentle. They knew both the children when they were babies, and they were so protective, I remember, do you remember Jaqui, how they would curl up with Thomas between them, and if someone they didn’t know came near they would growl, very softly? And how Celine would pull their tails and they would never bite her, but only push a little with their paw?’

Jacqueline, who was rather drunk—there was nothing to do but drink—replied loudly: ‘I remember how I used to worry that Magnus’ (the larger of the two) ‘would eat Celine in her cradle. But in the end he only mounted the cradle rather sensually, and it would rock.’

Irene laughed loudly at this.

The next day Irene, Jacqueline and Lola sat together on the porch, drinking murky coffee and watching the day brighten, almost imperceptibly behind a bank of cloud to the east. Celine had been up before all of them, running her finger through the dirt. Jacqueline looked at her daughter and thought:—I shouldn’t have had her, really I shouldn’t. What if she turns out ugly, what if she turns out beautiful? What if she turns out strong, or weak, as I am. What if there really is war, and she’s raped?

It was harder to worry about her son, who she did not quite consider a real person.

—But then again, she thought, looking down at her dress, thinking of the things in the house behind her that were hers, the things of hers in the house in Paris.

—Then again.

‘What are you thinking about, old schemer?’ asked Lola. ‘It’s not often I see a look like that on your face.’

‘Nothing’ said Jacqueline. ‘What are you going to draw tonight?’

‘Dicks’ said Lola, closing her eyes and tilting her chin up to the sky.

They organised trips for their own entertainment packing up what food the cook could spare for them (she saved most for the lavish evening meal, acting on instruction) and traipsing off to the strip of dirty beach where the children built sandcastles that stained their hands brown. They would drive a little out of town and walk through sad worn grasses and stare into the long bleak sky. Irma (the poet) remarked on the leaching of colour, as she picked at a clump of flowering weeds. Alex put his arm around her, the two little black spots on the landscape, her with her black hair and her worn black dress, and he with his too large black jacket and his black framed glasses and his black beard.

‘No my darling.’ he said, ‘Nothing is leaching out of anything. It is only a long autumn this year! See the fungus at the bottom of that tree: such a yellow! See the tiny red bugs scurrying by your feet- so bright! And this mud between the stalks of grass- so wet and shining, like a brown eye!’ He went on and on and on like this, until at last Irma was forced to laugh, and the rest of them laughed to and they all laughed even harder (though, Jacqueline said ‘we shouldn’t, we shouldn’t!’, wiping tears from her eyes) when Thomas, running, running, full tilt over the wide sad land, looked behind him to shout at his sister and went with a yelp right over a log.

Fernan, though self possessed, would talk to you about anything. He was very explicit when discussing sexual matters, very sympathetic if you told him your sadnesses. He didn’t shy away from difficult conversation and would answer honestly and thoughtfully if you asked him anything, about himself, or yourself, or the world. Nonetheless, Pierre went too far that night at dinner. They were talking about loss, and Pierre bought up Fernan’s first wife and son, who none of them had met. They had died years ago of influenza, when Fernan himself was only twenty five. Fernan said nothing, and before the silence deepened Lola began to talk about her ex husband, the famous painter.

‘That was a loss, like losing a limb.’ she said. ‘But the fucking limb was diseased.’

Fernan was not quiet for long, soon laughing with the rest of them at a story Lola was telling them, an awful story really, about finding a woman climbing out of the window of a bathroom in the house she had shared with the famous painter. Later he bent over the game of squares with his usual intensity. But when he lifted his body away from the paper, there was nothing in his square but a mass of mourning charcoal black.

Celine had stayed in the living room that evening, and Jacqueline saw her stare at Fernan for a long time after the paper had moved away from him, understanding in the insatiable way of children that she was witness to something which might otherwise have been hidden from her.

It was somehow inconvenient for all of them to admit that Alf and Andre were having an affair. If Jaqueline had spoken about it with, say Lola, she might have said, ‘Well goodness, people can do whatever they like can’t they? I mean it’s none of my business what they do with each other, just as it’s none of their business what I do with Pierre.’ Lola would probably respond in the same way she has the last time the love of men for men was discussed: ‘They are kinder than other men to me I’ve found, and yet I resent them for not finding me attractive, and I worry that if a man doesn’t think he might get to fuck you, what then will he think you have to offer?’

Jaqueline had found this position surprising. Lola had kept company with plenty of men who appeared not to want to fuck her (including, she thought cruelly, her husband the famous artist), and often spoke of what a relief it was. Jacqueline herself had always, in the very uptight manner of a properly brought up lady, been made acutely aware of her fuckability, it’s value in the market at large. She had been taught how to use this currency while seeming to hide it, like a miser. Pierre was the first man to treat her body as though it might be a container for her own desire. It was for this reason that she continued to love him, though it was clear he taught this lesson to other women too. Or rather, she certainly had loved him. She didn’t feel much for anyone these days. It was hard for emotion to make its way out from under the wide flat blanket of fear. Lola said that when the storm broke and war started it would be easier to breathe, but Jacqueline did not have the courage to wish for this to come sooner, though come she knew it must.

There were even fewer letters from Paris now, and none held onto the society lightness of previous months. Lola received a letter from her ex-husband, that she read in silence on the porch, before setting fire to it with her cigarette lighter. Celine was impressed by the gesture.More letters came from the town house, remarking with increasing urgency on the food shortages, especially of meat. Pierre eventually sent instructions to the servants to shoot the dogs. A letter came back saying they had already done so.

Thomas, in the absence of any other way of getting his sister’s companionship, had returned to drawing the kolams with her outside. He could not match her obsession, so often after a couple which he would scratch out with frustration more often than not, he would just sit beside her as she worked, having long one sided conversations as the light lasted. Sometimes, if she stopped to put her straggling light hair back from her face, or stretch her arms, Celine would reward his presence with a smile, but that was it. Everyone had become too depressed to tell her to watch the hem of her dress as she squatted down. She would make a line and rub it out, make it and rub them out, until some particular qualification had been satisfied. She had her father’s hand, it seemed, for they came out very steady. She had begun to dream of them, the pattens growing behind her eyes, the expansion relentless, for there was no end to them, no necessary end. After she confided this to her mother, Jacqueline dreamed of them too. Lola said that once, when she had drunk something meant to bring on visions and spent twenty four hours in a state of horrified ecstasy, she too had seen them, these infinite coruscations, in relentless technicolor: ‘I saw them everywhere,’ she said. ‘In flashes I would for months. I realised that they are the substance of the universe, the filaments of God. I still believe it sometimes. Perhaps this is how Celine has come to see things. Somewhere up there is a goddess who does not take her eyes from the pattern. Or perhaps that is what this is, this awful dead time, with death before us and behind. She has taken her hand from the ground, to stretch, or to take a sip of water. And we must trust that when she has taken the time she needs she will resume her drawing once again.’

Poor Lola, thought Jaqueline, she is so mad now, but I do love her.

Several nights later Celine roused herself from her customary doze after dinner, and asked if she might participate in the drawing. Her father gently told her ‘Darling, then one of us must make room for you, see? We have already drawn the eight squares.’ He looked at his lovely daughter

—How thin and awkward she has become.

Jaqueline saw him looking. God help me, she thought.

‘Oh for goodness sake Pierre!’ said Irene ‘What a ridiculous thing to say! All that is needed is for someone to step out and let her have their square, and of course I will do so! What would you like to draw with Celine?’

‘I have a pencil,’ said Celine, suddenly shy. ‘An excellent choice’ said Fernan.

‘Though you may borrow my coloured pencils if you would like,’ said the brooding Andre.

Celine’s kolam amazed those who had not seen her do them on the ground outside. It was less the image itself, which though symmetrical, did not hold it’s own against the elaborate stories the other pictures told. It was watching her do it in the flickering candlelight, with her stub of pencil, her fingers gliding, guiding the lead in it’s consistent and limitless curves. It seemed to those watching that her hand was moving for long minutes, and they all watched without a move, with barely a breath between them. When she took her pencil from the page the beginning and the end of the pattern joined so seamlesley that none could find it.

‘That’s quite a gift you have Celine.’ said Fernan quietly.

As was customary they all signed the back, and as Celine was too young to have a signature she printed her name quite clearly, Celine Charron. However the work was always attributed to Irene, or even sometimes to Antonio, because later he developed an interest in geometry, though those works contained nothing like the shape Celine had drawn. These errors were made in Celine’s lifetime, but she never contested them.

The morning after Celine took Irene’s place in the game of squares, there was a ship, and there were berths. Not enough for all of them, and it was agreed without argument that Jaqueline and the children should go first. So that easily resolved the question of squares, and there were no more kolams, nothing drawn in the dirt of the road any more.

‘Oh!’ said Lola, throwing her head back as they all sunbathed in the watery sun of the porch. ‘I never thought I’d miss throwing a ball for that bloody boy. But, now, who will fetch me my drink and my cigarette?’

Roisin DUNNETT is a writer based in London. Her short fiction and essays have appeared in Ambit, Tangerine Magazine, Hypocrite Reader and elsewhere. Her work is concerned with metamorphosis, fable and intimacy. She is currently working in the arts and on her debut novel.