SALVAGED

FROM OBSOLESENCE

Patrick LANGLEY, on ARKADY;

a conversation with Thomas CHADWICK‘It is not down in any map; true places never are.’

—Herman Melville, Moby Dick

—Herman Melville, Moby Dick

Arkady is Patrick Langley’s first novel. Set in the urban margins of an unnamed city, the novel consists of six vivid

chapters that trace the ascent into adulthood of two brothers: Jackson and

Frank. At the heart of the narrative are Patrick’s striking descriptions of

urban environments, which appear to exist not so much as a foil to the characters’ struggle but

simply as the texture of the landscape in which they live. In that sense, as

much as Arkady undoubtedly touches on

the ravages of late capitalism, Jackson and Frank’s story is one of two

brothers learning how to live. Hotel’s Thomas CHADWICK spoke with

LANGLEY via email about Arkady ahead

of its publication this week.

![]()

Arkady feels deeply rooted in the present

day. I wanted to open by asking about the origin of the book. Was there was a

particular event or incident that prompted it or was it written in response to

something more general?

There are moments in Arkady that were directly inspired by recent history. The collapse of Lehman Brothers, the student protests of 2010, the riots of 2011, and the housing crisis are all present in the novel in oblique, refracted ways. But rather than responding to any specific event, I was trying to capture something about the emotional texture of urban life in the post-crash era. In the midst of the bitterness and anger of those years there was a countervailing hope, however naïve, that a time of crisis could offer an opportunity for change. It wasn’t only Britain, of course. The Arab Spring, Occupy Wall Street—clearly something was in the air.

But there’s a reason I wrote a novel rather than nonfiction. I think this has something to do with how global events trickle into and alter the psyche; how zeitgeists are felt in the blood. For me, this tends to manifest at the level of mental images, rather than fully formulated thoughts. I saw two boys in Deptford Creek, surrounded by abandoned boats, as sunshine glistened on the low-tide mud. I saw the body of a man on a beach in the slanting rain, pylons stepping off into the flatlands behind him. I saw a toddler in a wheeled suitcase, laughing as his brother dragged him through scorching dust. I don’t know where these images came from, but to me they were co-ordinates or constellations, points across which to map the outlines of a story.

There were two things about this book that struck me as both vivid and precise: the first is the setting—it seemed to me to be located not in a vague dystopian future but rather specifically in the margins of our post-industrial present; the second is the relationship between the two brothers, who appear to view each other with tenderness and suspicion in equal measure. I wondered if you could speak about the novel’s development. Did you begin with the brothers’ relationship or was the precision of the urban environment always on your mind?

It began with the brothers, and hopefully stays with them. The tough, torturous love that exists between Jackson and Frank is really what pulled me through the novel, what I was most interested in. Tenderness and suspicion is exactly right: they’re constantly orientating themselves in relation to one another, and in relation to the world, according to how much of themselves they are prepared to make vulnerable.

I also wanted to capture something about the odd, slanted beauty of the urban landscape in which I grew up, to offer a panorama of startling details, however lowly their composition. Dust, rubble, moss, rain, concrete, knotweed, mud, glass—these are the elements out of which the world of Arkady is built. Any writing set in an urban environment inevitably risks being labelled as “gritty” or “grim” or whatever. But to me all these things are quite beautiful. You just have to look at them precisely, as you say.

While there are hints, the name and location of the urban space is never made explicit. What was the thinking behind the decision to not set the book in a specific city?

When I began writing, I thought the story was set in London. But I was wary of the literary baggage that the city carries, and of the obligation that naming a place inspires to reflect it faithfully. So I decided to ban certain words. It began as a crude kind of Oulipian restraint, really: no street names! no place names! I wanted the world of Arkady to shimmer and float as a possibility, a kind of warning or bad dream, as well as being rooted in detail, in visual texture, so that the reader felt convinced by the concrete reality of the place if not always quite sure where, exactly, it was. In the back of my head was that line from Moby Dick: “It is not down in any map; true places never are.” And placing two brothers at the centre of a story unavoidably strikes a mythic register, outside the specificities of time and place. There they are in the background, hovering in the sky: Romulus and Remus, Castor and Pollux, Cain and Abel.

It’s also something to do with my influences. I have a deep and complicated fascination with the work of Derek Jarman, who in films like Jubilee and The Last of England sought to bewitch the landscape of grief and dereliction he saw around him, to conjure something a mythos—part punk, part baroque, part Blakean dream-vision—from a country being crushed and dulled by Thatcher. Also on my mind were The Notebook by Agota Kristof, a tale of two brothers which has the warped, nightmarish intensity of a fairy tale, and We The Animalsby Justin Torres, where the world the young boys inhabit feels primal and immediate, driven by appetite, stripped of names.

I’m intrigued by what you describe as your crude Oulipian restraint. Did you have any other rules in mind as you worked on this book?

In an earlier and messier version, the story jumped around quite a bit, and I had a whole set of chapters describing Jackson’s teenage years. When I re-read that draft, it felt stodgy and aimless. And so I decided to impose a restraint, which was to have long chapters, written in present tense and covering, in real time, pivotal moments in the brothers’ lives. That was a useful constraint, which quickened and sharpened the story. I had in mind a trio of unlikely influences here: Human Acts by Han Kang; The Line of Beauty by Alan Hollinghurst; and the Melrose novels by Edward St Aubyn. In their quite different ways, all of these books make use of lacunae: they jump from one point or perspective to another, encouraging the reader to join the dots.

The novel raises some interesting questions about property. One of the chief villains within the novel’s urban environment is not an individual but a developer, Pendragon, memorably described as a “serpent-headed hydra of neo-liberal greed”. Yet at the same time the brothers appear to long for the personal space and security that something akin to private property provides, they choose not to live in the Red Citadel with the other protestors but stay on their boat just outside. Were you thinking about the complexity of property when you worked on this book?

Jackson and Frank have a conflicted relationship with property. They scorn and deride the bourgeois ideal of home ownership, but at the same time covet what they can’t have. Jackson prides himself on being footloose and nomadic. Then again, he craves a roof over his head, and somewhere to sleep without the threat of getting beaten up by bailiffs. The boat appeals to him because it’s both property and not: a home cut loose from land, salvaged from obsolescence, reclaimed.

Danny Dorling’s All That Is Solid and Anna Minton’s Ground Control were important to me while I wrote the book, as were the activities of groups like Focus E15, a group of young mothers who occupy disused housing in East London. I was briefly and half-heartedly an activist myself, sleeping in an occupied home in north London, and attending meetings and workshops. One thing I was struck by, in that occupation, was the diversity of people I met. Polite, middle-class liberals; hardened squatters; idealistic Communists; refugees— everyone was thrown together, and briefly united by the shared belief that the government had betrayed its most vulnerable constituents. Another important influence on Arkady was The Good Terrorist by Doris Lessing. She captures exactly the strange mixture of comradeship and friction that exists in those radical communities.

For several chapters the brothers use canals to travel through the urban space. What prompted you to make canals the central network that the brothers navigate as opposed to say roads or railways?

Bodies of water are present, often actively so, at important moments in the novel. In the opening chapter there is an incident at sea, though neither the brothers nor the reader witness it. There’s the city itself, which is built around a river, and whose outskirts are riddled with streams. And in the final chapter of the novel, small floods refresh and destabilise the landscape. Canals were the obvious mode of transport, in that sense. They reinforced a theme.

At one point in the book, Jackson starts reading Foucault’s essay Of Other Spaces off his phone. Frank stops listening because he finds his older brother’s theorising insufferable. Foucault ends his meditation on heterotopias—the “other places” of the essay’s title—with a strange ode to boats. These vessels, which facilitated the horrors of colonisation, are equally a repository of imagination and dreaming. He writes that the archetypical boat is “a floating piece of space”. That description is so simple it sounds almost stupid. But it’s evocative, too. In the context of property and ownership, of the flux of adolescence, of the struggle to find one’s place in the world, Foucault’s idea of the boat—unmoored from space and social hierarchy, both imaginary and mercantile, terrible and childish—seemed richly evocative of the predicament and possibility of Jackson and Frank’s position.

Thinking more broadly about different urban histories, I’m interested by your desire to capture something of the “emotional texture of urban life in the post-crash era”. As much as Arkady is set in capitalism’s most recent crisis, the landscape is full of the traces of earlier crises—I’m thinking in particular of the many former manufacturing spaces that the various characters inhabit, as well as other industrial legacies such as canals and dykes. Do you think that urban space encodes our experience of capitalism—and particularly capitalism in crisis—in ways that other images cannot?

Urban spaces render blatantly (and literally) concrete inequalities that might otherwise feel abstract or distant. Emblematic of this in London are the Heygate Estate, where social housing has been demolished to make way for luxury developments, and the Shard, a symbol of extreme wealth which towers over everything and dominates the skyline. Meanwhile we have a housing crisis and a homelessness crisis, with “poor doors” and anti-homelessness spikes and so on. In urban space, the crises you identify feel obscenely obvious, and totally unignorable. I wanted to set the brothers amid that. They are at the sharp end of inequality, yet they can see the city changing all around them, pricing them out. That creates an immediate tension. Their world is out of joint.

The novel raises some important points about political protest. Do you see either of the brothers as apathetic?

One of the dilemmas the brothers face is whether or not to engage in a protest, whether to risk their own position in order to contribute to a greater cause. To become involved with a group of strangers, however exciting the prospect might be, goes against the brothers’ deepest, most self-protective instincts. Jackson and Frank have always looked after each other, and only each other. The scope of their care is extremely narrow. They don’t try to change the world, at least initially, because they don’t believe they can. And they have more pressing things to worry about, such as what to eat, or where to sleep. For many people, after all, protest is a luxury.

Then, about halfway through Arkady, the brothers encounter the Red Citadel. Here they meet a group of uncompromising activists driven by the belief that direct, even violent rebellion is not only legitimate but necessary; that to hurl rocks and bottles might genuinely improve the world. That’s a seductive, empowering idea for them—and one that I feel sceptical of. So yes, in one important sense the brothers are indeed apathetic. But apathy is an infection they’re constantly trying to rid themselves of, and in many ways they’re stubbornly proactive. It’s more a question of where their allegiances lie: with each other, or with a wider movement they’ve only just discovered exists?

You mentioned earlier that the brothers orient themselves in relation to each other and the world according to how much of themselves they are prepared to make vulnerable. Do you see a similar vulnerability in the novel form itself not only for the characters within it but also for the writer outside it?

I think so. There’s the vulnerability that comes from putting yourself into a book, however splintered and sublimated that self-portrayal might be. And there’s the vulnerability that comes from having other people read and critique the work, too. But it depends on which kind of novel you write. Recently there has been a lot of discussion about autofiction, and the connotations of immediacy, honesty, and vulnerability the genre entails. It became apparent to me early on that I didn’t want to go down that route with Arkady, but that I wanted the characters to in some sense reflect aspects of my character that I might otherwise have spoken about more flatly.

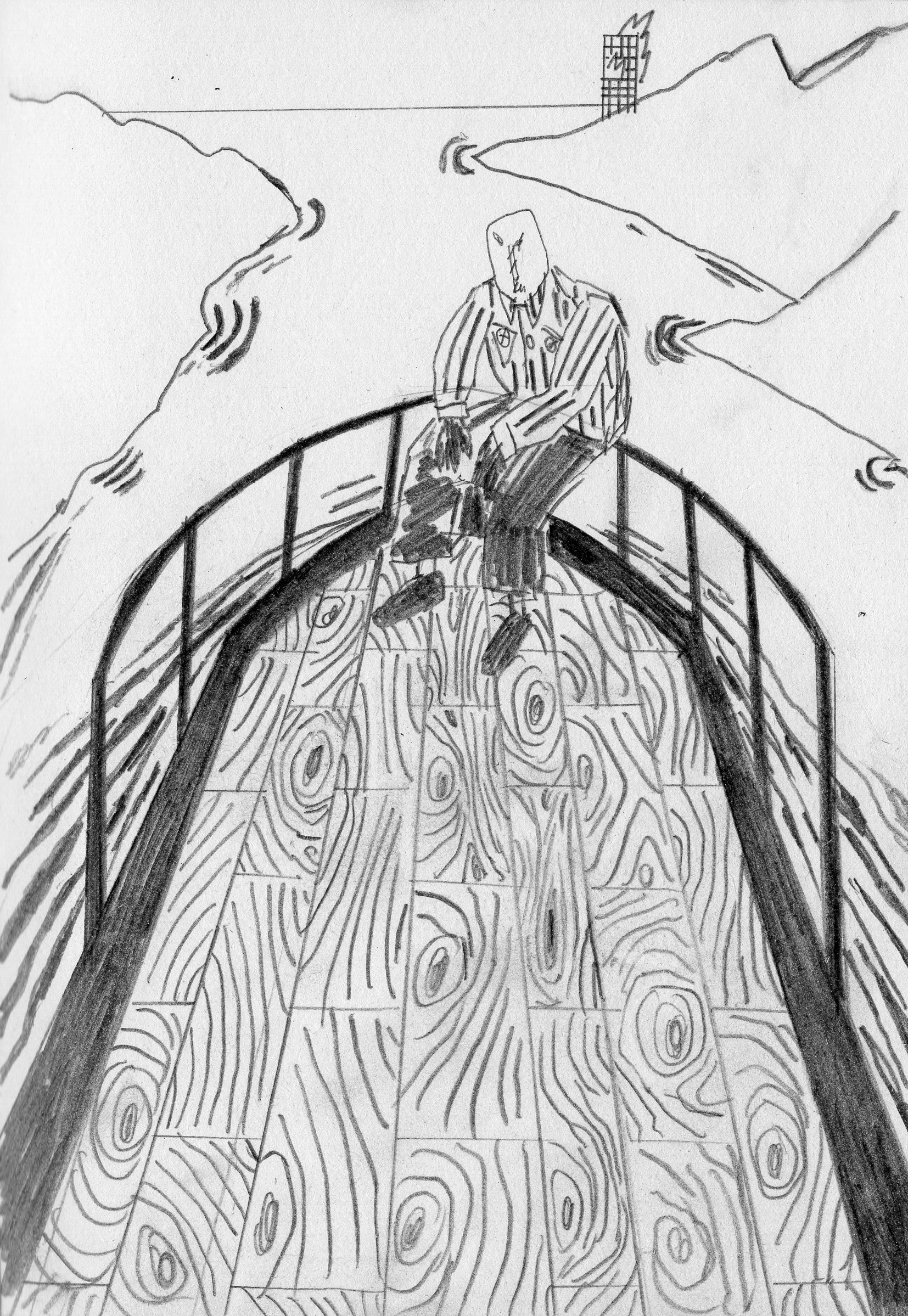

I’ve been thinking a lot about the word “Arkady”. It’s obviously the title of the novel, but it’s also the name Frank assigns to a “blank faceless head” he repeatedly draws as well as being the name Jackson and Frank give to their barge. A brief Google search produces a ream of references (a Soviet writer, a Moldovan-American composer, a shopping centre in Prague). How did you arrive at the word?

About a decade ago, after moving into an unfurnished house in south-east London, I constructed a mannequin from clothes stuffed with old Ikea packaging. He looked a bit like Rodin’s Thinker, but faceless and sinister. For a head, I stuffed a black plastic shopping bag, like you’d get from a corner shop, and slotted a cardboard ‘cigarette’ into a small incision I had cut for his mouth. He became the basis for posters and drawings, in which I imagined the character playing the central role in a series of films. I called him Arkady, but I can’t remember where the name came from. By that point I would have read Roadside Picnic (1972), by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, which might explain it.

When it came to writing the novel, it struck me that the name resonated with the themes I was trying to explore, as well as providing a kind of ghostly companion to Frank. (I wanted the reader to feel that Frank’s upbringing had affected his inner life in indirect ways, manifesting as invented characters and drawings.) Most obviously, Arkady sounds like Arcadia, which in an ironic way describes a lost or longed-for place of safety towards which the brothers strive—the name literally means “of Arcadia”, I believe. And that first syllable, ark, hints at the boat as both a refuge from a hostile world and a generative object.

Finally, and to step back from Arkady a little, you also publish work as an art critic. Was it always your ambition to write a novel or did the novel develop from the criticism so to speak?

I’ve always wanted to write novels, but it took me a while to develop the confidence to actually do it. And meanwhile I was, and still am, fascinated by art—its capacity to dumbfound, irritate, move, inspire, and estrange me. I think of the fiction and the criticism as quite separate. Unlike, say, Ben Lerner or Lynne Tillman, who fold their criticism into the fiction and vice versa, Arkady is deliberately, and pretty straightforwardly, telling a story. But there are overlaps and seepages between the two disciplines, which I’m not always entirely aware of. The character Nell, who appears in Arkady as a kind of surrogate mother for Jackson and Frank, is a sculptor. The descriptions of her work are a whispery, indirect homage to Eva Hesse, whose sculptural forms fascinate me, while the wonky garden in which she chats with Frank is inspired by Jarman’s, in Dungeness, with its twisted iron and driftwood sculptures. There is a long history of artists occupying derelict spaces, especially in London, so there’s an overlap with the political side of things too. Several years ago I heard someone describe artists as the “shock-troops of gentrification”. I’ve never forgotten it.

There are moments in Arkady that were directly inspired by recent history. The collapse of Lehman Brothers, the student protests of 2010, the riots of 2011, and the housing crisis are all present in the novel in oblique, refracted ways. But rather than responding to any specific event, I was trying to capture something about the emotional texture of urban life in the post-crash era. In the midst of the bitterness and anger of those years there was a countervailing hope, however naïve, that a time of crisis could offer an opportunity for change. It wasn’t only Britain, of course. The Arab Spring, Occupy Wall Street—clearly something was in the air.

But there’s a reason I wrote a novel rather than nonfiction. I think this has something to do with how global events trickle into and alter the psyche; how zeitgeists are felt in the blood. For me, this tends to manifest at the level of mental images, rather than fully formulated thoughts. I saw two boys in Deptford Creek, surrounded by abandoned boats, as sunshine glistened on the low-tide mud. I saw the body of a man on a beach in the slanting rain, pylons stepping off into the flatlands behind him. I saw a toddler in a wheeled suitcase, laughing as his brother dragged him through scorching dust. I don’t know where these images came from, but to me they were co-ordinates or constellations, points across which to map the outlines of a story.

There were two things about this book that struck me as both vivid and precise: the first is the setting—it seemed to me to be located not in a vague dystopian future but rather specifically in the margins of our post-industrial present; the second is the relationship between the two brothers, who appear to view each other with tenderness and suspicion in equal measure. I wondered if you could speak about the novel’s development. Did you begin with the brothers’ relationship or was the precision of the urban environment always on your mind?

It began with the brothers, and hopefully stays with them. The tough, torturous love that exists between Jackson and Frank is really what pulled me through the novel, what I was most interested in. Tenderness and suspicion is exactly right: they’re constantly orientating themselves in relation to one another, and in relation to the world, according to how much of themselves they are prepared to make vulnerable.

I also wanted to capture something about the odd, slanted beauty of the urban landscape in which I grew up, to offer a panorama of startling details, however lowly their composition. Dust, rubble, moss, rain, concrete, knotweed, mud, glass—these are the elements out of which the world of Arkady is built. Any writing set in an urban environment inevitably risks being labelled as “gritty” or “grim” or whatever. But to me all these things are quite beautiful. You just have to look at them precisely, as you say.

While there are hints, the name and location of the urban space is never made explicit. What was the thinking behind the decision to not set the book in a specific city?

When I began writing, I thought the story was set in London. But I was wary of the literary baggage that the city carries, and of the obligation that naming a place inspires to reflect it faithfully. So I decided to ban certain words. It began as a crude kind of Oulipian restraint, really: no street names! no place names! I wanted the world of Arkady to shimmer and float as a possibility, a kind of warning or bad dream, as well as being rooted in detail, in visual texture, so that the reader felt convinced by the concrete reality of the place if not always quite sure where, exactly, it was. In the back of my head was that line from Moby Dick: “It is not down in any map; true places never are.” And placing two brothers at the centre of a story unavoidably strikes a mythic register, outside the specificities of time and place. There they are in the background, hovering in the sky: Romulus and Remus, Castor and Pollux, Cain and Abel.

It’s also something to do with my influences. I have a deep and complicated fascination with the work of Derek Jarman, who in films like Jubilee and The Last of England sought to bewitch the landscape of grief and dereliction he saw around him, to conjure something a mythos—part punk, part baroque, part Blakean dream-vision—from a country being crushed and dulled by Thatcher. Also on my mind were The Notebook by Agota Kristof, a tale of two brothers which has the warped, nightmarish intensity of a fairy tale, and We The Animalsby Justin Torres, where the world the young boys inhabit feels primal and immediate, driven by appetite, stripped of names.

I’m intrigued by what you describe as your crude Oulipian restraint. Did you have any other rules in mind as you worked on this book?

In an earlier and messier version, the story jumped around quite a bit, and I had a whole set of chapters describing Jackson’s teenage years. When I re-read that draft, it felt stodgy and aimless. And so I decided to impose a restraint, which was to have long chapters, written in present tense and covering, in real time, pivotal moments in the brothers’ lives. That was a useful constraint, which quickened and sharpened the story. I had in mind a trio of unlikely influences here: Human Acts by Han Kang; The Line of Beauty by Alan Hollinghurst; and the Melrose novels by Edward St Aubyn. In their quite different ways, all of these books make use of lacunae: they jump from one point or perspective to another, encouraging the reader to join the dots.

The novel raises some interesting questions about property. One of the chief villains within the novel’s urban environment is not an individual but a developer, Pendragon, memorably described as a “serpent-headed hydra of neo-liberal greed”. Yet at the same time the brothers appear to long for the personal space and security that something akin to private property provides, they choose not to live in the Red Citadel with the other protestors but stay on their boat just outside. Were you thinking about the complexity of property when you worked on this book?

Jackson and Frank have a conflicted relationship with property. They scorn and deride the bourgeois ideal of home ownership, but at the same time covet what they can’t have. Jackson prides himself on being footloose and nomadic. Then again, he craves a roof over his head, and somewhere to sleep without the threat of getting beaten up by bailiffs. The boat appeals to him because it’s both property and not: a home cut loose from land, salvaged from obsolescence, reclaimed.

Danny Dorling’s All That Is Solid and Anna Minton’s Ground Control were important to me while I wrote the book, as were the activities of groups like Focus E15, a group of young mothers who occupy disused housing in East London. I was briefly and half-heartedly an activist myself, sleeping in an occupied home in north London, and attending meetings and workshops. One thing I was struck by, in that occupation, was the diversity of people I met. Polite, middle-class liberals; hardened squatters; idealistic Communists; refugees— everyone was thrown together, and briefly united by the shared belief that the government had betrayed its most vulnerable constituents. Another important influence on Arkady was The Good Terrorist by Doris Lessing. She captures exactly the strange mixture of comradeship and friction that exists in those radical communities.

For several chapters the brothers use canals to travel through the urban space. What prompted you to make canals the central network that the brothers navigate as opposed to say roads or railways?

Bodies of water are present, often actively so, at important moments in the novel. In the opening chapter there is an incident at sea, though neither the brothers nor the reader witness it. There’s the city itself, which is built around a river, and whose outskirts are riddled with streams. And in the final chapter of the novel, small floods refresh and destabilise the landscape. Canals were the obvious mode of transport, in that sense. They reinforced a theme.

At one point in the book, Jackson starts reading Foucault’s essay Of Other Spaces off his phone. Frank stops listening because he finds his older brother’s theorising insufferable. Foucault ends his meditation on heterotopias—the “other places” of the essay’s title—with a strange ode to boats. These vessels, which facilitated the horrors of colonisation, are equally a repository of imagination and dreaming. He writes that the archetypical boat is “a floating piece of space”. That description is so simple it sounds almost stupid. But it’s evocative, too. In the context of property and ownership, of the flux of adolescence, of the struggle to find one’s place in the world, Foucault’s idea of the boat—unmoored from space and social hierarchy, both imaginary and mercantile, terrible and childish—seemed richly evocative of the predicament and possibility of Jackson and Frank’s position.

Thinking more broadly about different urban histories, I’m interested by your desire to capture something of the “emotional texture of urban life in the post-crash era”. As much as Arkady is set in capitalism’s most recent crisis, the landscape is full of the traces of earlier crises—I’m thinking in particular of the many former manufacturing spaces that the various characters inhabit, as well as other industrial legacies such as canals and dykes. Do you think that urban space encodes our experience of capitalism—and particularly capitalism in crisis—in ways that other images cannot?

Urban spaces render blatantly (and literally) concrete inequalities that might otherwise feel abstract or distant. Emblematic of this in London are the Heygate Estate, where social housing has been demolished to make way for luxury developments, and the Shard, a symbol of extreme wealth which towers over everything and dominates the skyline. Meanwhile we have a housing crisis and a homelessness crisis, with “poor doors” and anti-homelessness spikes and so on. In urban space, the crises you identify feel obscenely obvious, and totally unignorable. I wanted to set the brothers amid that. They are at the sharp end of inequality, yet they can see the city changing all around them, pricing them out. That creates an immediate tension. Their world is out of joint.

The novel raises some important points about political protest. Do you see either of the brothers as apathetic?

One of the dilemmas the brothers face is whether or not to engage in a protest, whether to risk their own position in order to contribute to a greater cause. To become involved with a group of strangers, however exciting the prospect might be, goes against the brothers’ deepest, most self-protective instincts. Jackson and Frank have always looked after each other, and only each other. The scope of their care is extremely narrow. They don’t try to change the world, at least initially, because they don’t believe they can. And they have more pressing things to worry about, such as what to eat, or where to sleep. For many people, after all, protest is a luxury.

Then, about halfway through Arkady, the brothers encounter the Red Citadel. Here they meet a group of uncompromising activists driven by the belief that direct, even violent rebellion is not only legitimate but necessary; that to hurl rocks and bottles might genuinely improve the world. That’s a seductive, empowering idea for them—and one that I feel sceptical of. So yes, in one important sense the brothers are indeed apathetic. But apathy is an infection they’re constantly trying to rid themselves of, and in many ways they’re stubbornly proactive. It’s more a question of where their allegiances lie: with each other, or with a wider movement they’ve only just discovered exists?

You mentioned earlier that the brothers orient themselves in relation to each other and the world according to how much of themselves they are prepared to make vulnerable. Do you see a similar vulnerability in the novel form itself not only for the characters within it but also for the writer outside it?

I think so. There’s the vulnerability that comes from putting yourself into a book, however splintered and sublimated that self-portrayal might be. And there’s the vulnerability that comes from having other people read and critique the work, too. But it depends on which kind of novel you write. Recently there has been a lot of discussion about autofiction, and the connotations of immediacy, honesty, and vulnerability the genre entails. It became apparent to me early on that I didn’t want to go down that route with Arkady, but that I wanted the characters to in some sense reflect aspects of my character that I might otherwise have spoken about more flatly.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the word “Arkady”. It’s obviously the title of the novel, but it’s also the name Frank assigns to a “blank faceless head” he repeatedly draws as well as being the name Jackson and Frank give to their barge. A brief Google search produces a ream of references (a Soviet writer, a Moldovan-American composer, a shopping centre in Prague). How did you arrive at the word?

About a decade ago, after moving into an unfurnished house in south-east London, I constructed a mannequin from clothes stuffed with old Ikea packaging. He looked a bit like Rodin’s Thinker, but faceless and sinister. For a head, I stuffed a black plastic shopping bag, like you’d get from a corner shop, and slotted a cardboard ‘cigarette’ into a small incision I had cut for his mouth. He became the basis for posters and drawings, in which I imagined the character playing the central role in a series of films. I called him Arkady, but I can’t remember where the name came from. By that point I would have read Roadside Picnic (1972), by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, which might explain it.

When it came to writing the novel, it struck me that the name resonated with the themes I was trying to explore, as well as providing a kind of ghostly companion to Frank. (I wanted the reader to feel that Frank’s upbringing had affected his inner life in indirect ways, manifesting as invented characters and drawings.) Most obviously, Arkady sounds like Arcadia, which in an ironic way describes a lost or longed-for place of safety towards which the brothers strive—the name literally means “of Arcadia”, I believe. And that first syllable, ark, hints at the boat as both a refuge from a hostile world and a generative object.

Finally, and to step back from Arkady a little, you also publish work as an art critic. Was it always your ambition to write a novel or did the novel develop from the criticism so to speak?

I’ve always wanted to write novels, but it took me a while to develop the confidence to actually do it. And meanwhile I was, and still am, fascinated by art—its capacity to dumbfound, irritate, move, inspire, and estrange me. I think of the fiction and the criticism as quite separate. Unlike, say, Ben Lerner or Lynne Tillman, who fold their criticism into the fiction and vice versa, Arkady is deliberately, and pretty straightforwardly, telling a story. But there are overlaps and seepages between the two disciplines, which I’m not always entirely aware of. The character Nell, who appears in Arkady as a kind of surrogate mother for Jackson and Frank, is a sculptor. The descriptions of her work are a whispery, indirect homage to Eva Hesse, whose sculptural forms fascinate me, while the wonky garden in which she chats with Frank is inspired by Jarman’s, in Dungeness, with its twisted iron and driftwood sculptures. There is a long history of artists occupying derelict spaces, especially in London, so there’s an overlap with the political side of things too. Several years ago I heard someone describe artists as the “shock-troops of gentrification”. I’ve never forgotten it.

Patrick LANGLEY is a writer who lives in London. He writes about art for various publications. He is an editor at Art Agenda and a contributing editor at The White Review. ARKADY is his first novel, and was published by Fitzcarraldo Editions. The above image is one of LANGLEY’s unused illustrations from the novel.