Michael

ALMEREYDA

TERMITE

DELUXE

Manny Farber, Ingenious Zeus

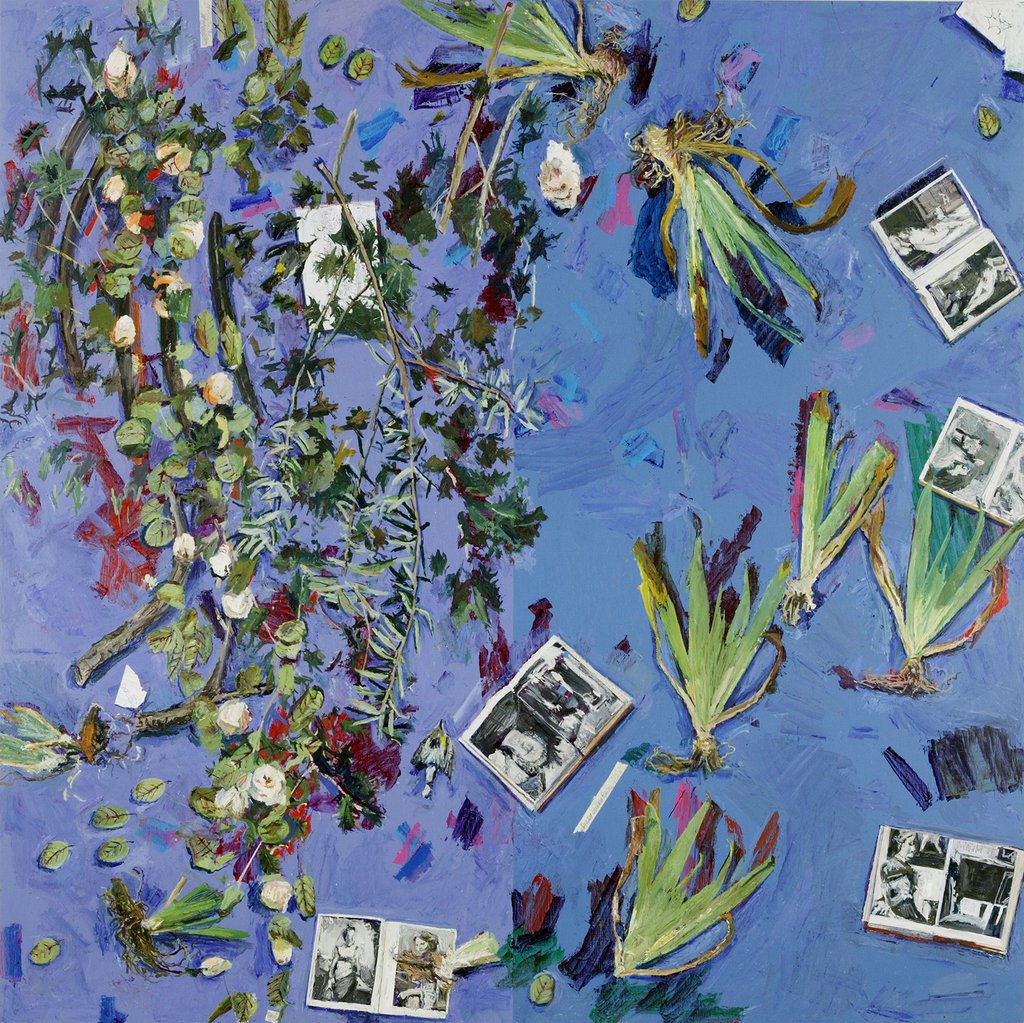

Manny Farber, Ingenious Zeus oil on board, 72” x 72” (2000)

“What is the point of being a little boy if you are going to grow up to be a man?” — Gertrude Stein, Everybody’s Autobiography

In my memory, an essential part of my adolescence was spent drifting through vast San Diego parking lots with Manny Farber, trying to figure out where he had parked his car.

We met in 1976, when I was 16 or 17; Manny was 59. I’d bicycled to Orange Coast Community College to see him present Fassbinder’s Effi Briest. Manny brought the movie with him, the actual film reels, but got lost on the freeway and arrived more than an hour late. When he began his introduction, the auditorium lights dimmed and the projector flashed on, beaming onto his face. He tried talking, a startled sentence or two, and I felt I was catching a guest appearance by Professor Irwin Corey, the shambling, comic TV authority with wild eyes and windblown hair, one pedantic finger held high before declaring: “However...” Then Manny stepped out of the light—the stark equivalent of a vaudeville hook yanking him offstage.

Effi Briest is one of Fassbinder’s most beautifully measured, austere films, black- and-white, two hours and 15 minutes long. Manny never wrote about it, and I don’t remember the post-screening Q&A, only that it was brief, as the movie had run past midnight and the wearied audience was invited to disperse. I intercepted Manny outside, told him I’d just read his book and asked if he could talk about James Agee. Manny stared, then offered, in his quiet dry voice: “He was handsome as hell.” Realizing this was perhaps inadequate, he added, “He was heroic.” Then he said, “It’s late. Come to San Diego some time and we can talk.”

He must have supplied me with a phone number, and I must have called. I don’t remember the particulars, but within weeks I was on Amtrak’s Pacific Surfliner, shuttling past the orange groves of San Clemente, the white spheres of the San Onofre nuclear power plant and then, for a sustained stretch, the glittering ocean. Arriving in Del Mar, I was picked up by a student and ferried to Manny’s studio on the UCSD campus.

The jacket flap of Negative Space described its author as “a noted painter,” but his paintings were wholly new to me and I spent a lot of time, on that first visit, roaming around the studio, looking closely, nearly mute. The pale, slashed, scuffed color, and the way objects were given hard edges and outlines, reminded me of Degas, though Degas never got around to painting still lifes. I told Manny this. He didn’t seem displeased.

He hadn’t quite declared his retirement from film criticism, but writing, he insisted, was “killing” and “brutal,” whereas painting, plainly enough, seemed to yield actual pleasure. In the calm of his studio, the nutty professor image gave way to a more stalwart impression. You know from photographs that Manny was vivid—the deepset eyes, sharp nose, domelike brow—though photos don’t quite capture his deadpan charm, his air of antic irascibility or plain mischief. He had the body of an athlete, a workman: narrow hips, powerful arms. There was something rueful and shy in his bearing, but also a forthright- ness, a centeredness. It was common to see him holding a cowboy stance, one hand to his hip, his square tipped fingers slightly splayed—each finger broken, he’d tell you, in the course of carpentry jobs—and his head slightly tilted, a smile softening the lines of his face. He often seemed abashed, easily bewildered, and would fall into another pose while seated: his fingers would crawl up along his cranium, and stay near the top, sheltering and hiding his face. It was a kind of comic illustration of abject “thinking,” and he’d wake from it, or shrug it off, with sudden vivacity, a wisecrack, that smile.

Maybe shyness was our basic common ground. I was, I should explain, an introverted, saturnine kid, a reluctant teenager who preferred the company of adults. My one identifiable talent as a boy was for drawing and, by extension, painting, but my confidence in this way of understanding the world had been rattled when my family moved to California, transporting me, unconsulted, from the pastoral suburbs (as I remembered them) of Overland Park, Kansas to the synthetic paradise of Costa Mesa, where our new house seemed to have emanated from the adjacent golf course. I met Manny during my tormented fourth year of non-adjustment.

I was—need I elaborate?—odd, friendless; I hated school, spent lunch hours in the library, refused to be photographed, scarcely spoke. But I had started watching a lot of old movies—L.A. TV stations showed them all the time; the air, it seemed, was thick with movies—and I had fixed on James Agee, dead before I was born, as a ghostly patron saint, a suitably high-minded and self-destructive role model. I’d read all the Agee in print, and I wanted to project myself into a future where I’d make the kind of movies Agee proselytized for in his reviews and scripts, a notion of movie poetry distilled from the grain of documentary fact. I had a dim awareness that this was preposterous, but the idea was too absorbing to let go of.

And Manny, on some level, must have been sympathetic. Negative Space, after all, opens with a 1957 piece,“UndergroundFilms,”pretty much a precursor to arguments refined and flung around six years later in the gradually famous Termite Art essay. Agee is given pride of place when Manny veers off in the middle, announcing a fascinatingly mismatched private pantheon:

However, any day now, Americans may realize that scrambling after the obvious in art is a losing game. The sharpest work of the last thirty years is to be found by studying the most unlikely, self-destroying, uncompromising, roundabout artists. When the day comes for praising infamous men of art, some great talent will be shown in true light: people like Weldon Kees, the rangy Margie Israel, James Agee, Isaac Rosenfeld, Otis Ferguson, Val Lewton, a dozen comic-strip geniuses like the creator of “Harold Teen,” and finally a half-dozen directors such as the master of the ambulance, speedboat, flying-saucer movie: Howard Hawks.

(It’s curious to note, decades down the line, that half the listed names are still altogether obscure.)

“I liked him more than that,” Manny conceded, with real contrition, when I mentioned “Nearer My Agee to Thee,” his direct assessment of Agee’s posthumously collected film criticism, written as if to hold off an avalanche of misjudged Agee hero-worship. It’s a fairly caustic, corrosive piece in which affection is crowded out by mockery, dumb puns on Agee’s name, accusations of grandstanding and glibness. Agee’s “superabundant writing talent” and the “excessive richness” of his reviews are found wanting after Manny factors in Agee’s effortful moralizing and his supplication to “Big Art,” which allowed Agee to miss the value of “super-present-tense material” in the more modest movies Manny prized and praised. In the thick of it, Manny rates one of Agee’s finest virtues to be “a way of playing leapfrog with clichés, making them sparkle like pennies lost in a Bendix.” Even when I first read it, I marveled at this sentence. Who in the world would conjure this chain of associations—clichés, frogs, pennies in a washing machine—and find those words to pin them down? Why be so crazily precise in marrying physical description to abstract attributes? The language skates on the edge of sheer silliness. Decades later, Manny took up the same tack in his paintings, where leapfrogging clichés, in the form of toys and trains, tumble across tabletop arrangements to invoke his favorite films and the contradictory ingredients spilling in and out of them.

At any rate, Manny, that morning, was game to talk about Agee’s gift for talk, but also about how he’d sit silent when riding on a train, staring out the window, his face held close to the glass. Manny didn’t bother mentioning his friend’s drinking or womanizing, highlighted in a biography published just a few years later.1 But he remembered his generosity, his unstoppableness, during their would-be collaboration, a screenplay idea instigated by Agee—a romance framed by 24 hours like Minnelli’s The Clock. They sat side by side on a park bench and talked it through; or rather Agee talked, describing scenes in impossible detail while Manny listened, overwhelmed. “He was too smart for me,” was the glum summary. (Years later, Robert Walsh presented me with the unearthed, uncompleted manuscript for the project; Agee’s penciled writing was incredibly tiny, clotted and crabbed, smeared into the paper—an illegible fog.)

I met Patricia—she probably joined us for lunch—though it’s hard to separate my first impression from the abiding picture developed over time. She was warm, watchful, unassertive, mild, alert. Her softness stood in sharp contrast to his gruffness. She had a different grade or degree of shyness. I thought she was lovely and mysterious in the way that women hovering in the middle distance of Vuillard paintings are lovely and mysterious—to name one of her conspicuous influences at that time. It was easy to recognize that Manny was lucky to have her in his corner, and he was sensible enough to acknowledge his luck, though it tended to be channeled through praise for her work, muttered matter-of-factly and with a tinge of awe. “Patricia’s paintings are terrific. Look at the way she gets that line. It kills me.” Sure enough, I was at least as impressed with what she was up to in her canvases; it was closer to what I would have been doing if I kept painting, and what, in fact, I dabbled at later. The faded color snapshots from Patricia’s time spent on the Aran Islands were scattered about her studio, so you saw the paintings’ undisguised sources and could track the process of distillation, the assurance of her drawing, her eye for pattern and color, the airy quality of light within the paint.

I wanted to know about New York in the 40s and 50s, the Cedar Tavern crowd. Patricia and I listened like children as Manny admitted getting into a fist fight with Jackson Pollock, a lousy fighter, he was surprised to discover, and with Clement Greenberg, who was unexpectedly tough. The scuffle with Pollock somehow involved a bathroom door; the source of the dispute was lost in time. But the brawl with Greenberg, he remembered, was about Henry James. What about Henry James, I asked, with more than a little curiosity. That he could not remember.

I was invited back to Del Mar, and stayed the night, slept on the couch, shared breakfast. Within the year, they moved to Leucadia, to the house Manny died in 40 years later, a compact structure amidst rows of commercial greenhouses, less than five minutes from the beach. Over the next three years, my visits became something of a routine, a reassuring and reliable escape from other contexts and frames. While still officially a high school student, I was allowed to take classes at UC Irvine—a bowl-shaped campus constructed like a futuristic frontier town, bordered by dusty hills; Manny knew it and described how the students “roll around like marbles” along the intersecting paths. I became one of the marbles and, following Manny’s recommendation, took art history classes taught by Phil Leider, his former editor at Artforum, a spring-heeled pacer, explicator, and aphorist whose crowd-pleasing lecturing style seemed like a mashup of Manny Farber and Lenny Bruce. (Lucas Cranach’s mincing nudes, with their arabesquing backs, were compared to spirochetes. Picasso was “the last great artist whose life was kissed by God.” And so on.)

I was introduced to the inner circle of UCSD colleagues: Jean-Pierre Gorin, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Duncan Shepherd, and a few grad students closer to my age. I noticed that almost all Farber associates picked up a vocabulary for talking about movies in terms of “terrain” and “territory” while adopting hand gestures, consciously or not, that mirrored Manny’s, holding an index finger aloft, projecting it down a short vector, as if tracing a track on an imaginary map. And, spending time with Manny, it was nearly impossible to not take on his appreciation of the local landscape: the hectic Seuss-like foliage scamp- ering near and far across surrounding cliffs, bluffs, and arroyos. (Dr. Seuss, I learned, lived nearby; the man was simply reporting on what he saw outside his window and in his backyard, as Manny came to do. The La Jolla post office had to hire extra carriers to deliver the Doctor’s mail on his birthday. Surely, Dr. Seuss was the last great artist whose life was kissed by God.)

Manny thought it might be beneficial for me to meet his once-estranged daughter, Amanda, who was two years older than me, in the process of a hard-won realignment with her father. I remember a pale intense young woman, raven-haired, with big brown eyes and a disarming smile. The smile flashed when she talked about Werner Herzog’s offer to cast Manny in Stroszek, Herzog’s first American film, in which Manny would play a tractor-driving farmer, and Amanda the farmer’s daughter. I remember Manny’s furrowed brow and his simple certainty when he told me he turned Herzog down, avoiding potential glory and/or humiliation.

I graduated high school, just barely, on the strength of transferred UCI credits, and when I went east to Harvard (still looking for Agee, who was nowhere to be found) I studied art history, though none of my teachers measured up to Phil Leider. Visiting with Manny and Patricia during school breaks, I could talk with tolerable earnestness and detail about Piero della Francesca, George Stubbs, Cézanne, Matisse, Turner, Ruskin, Adrian Stokes, Goya, Robert Smithson, Leo Steinberg. These, as I remember it, were the painters and writers up for discussion. We also talked about Preston Sturges, Nick Ray and Nic Roeg, Robert Bresson, Orson Welles (especially Touch of Evil, which we all loved), and the New German Cinema. It was easy to agree, when the subject came up, that movie criticism was at a low ebb, that film reviewers had become dispensers of consumer reports, guys on TV wearing sweaters. (That said, by this time Roger Ebert had become Manny’s loyal friend and champion when they met up in festivals in Telluride and Venice.)

What did I have to offer them? Why did Manny and Patricia, after a fashion, adopt me? The questions hum in my head at this long distance, decades down the road. Jonathan Rosenbaum, in a 1994 essay he considers one of the best things he’s ever written,2 recounts in considerable detail his troubled year as Manny’s recruit in the UCSD film department, where he found himself in helpless competition with Jean-Pierre Gorin. Recognizing similarities in their childhoods, the presence of over-achieving brothers in both the Farber and Rosenbaum households, Jonathan concludes that the theme of his essay is sibling rivalry, while also noting that Manny, presiding over a variety of faculty members and students, had a talent for enticing younger men into imbalanced father-son relationships. In Routine Pleasures, Gorin’s multi-faceted documentary essay shot in 1985, you get an equally acute Farber portrait, though pointedly oblique, shaped around Manny’s absence since he declined, once again, to be filmed. Puttering model train enthusiasts in Del Mar serve as Farber surrogates, and two intricate Farber paintings get star treatment as Babette Mangolte’s camera glides across and inside them. (The paintings hold the screen with great verve.) But JP (as I came to know him) circles around Farber, the elusive curmudgeon, with speculative voice-over, commentary, and quips. At one point he admits: “It made for a story that all the shrinks in the audience would read as a search for the father, but which I kept seeing as an old-fashioned buddy story.” I could say something similar. During those years, I was pretty good at deflecting the thought that I was looking for a father figure in Manny, preferring to think of myself as a stand-in for the steadfast deaf-mute kid in Out of the Past, the resourceful sidekick who sticks close to Robert Mitchum and, you know, rescues him from a smug assassin with the deft tug of a fishing line. As far as I could tell, I’d won Manny’s approval by being near-silent and selfless, and by awarding his work my purist attention. Reading Manny and Patricia’s career-capping interview in Film Comment, I flattered myself with a private beam of identification when Manny singled out Jean-Luc Godard at the end of the piece:

I clocked a good deal of time in Manny’s studio, and accompanied him on errands, moving through shimmering parking lots as he groused, joked, and misplaced his car. I can recognize now what I dimly intuited at the time: I had a need to find in Manny’s presence, his example, and his implicit or outright guidance, both a fortification of my own awkwardness and multiple ways to escape it. I was drawn to his irreverence and his humility, his intransigence and his deadpan comic timing, his contempt for “corny” sentimentality and his suspicion that things are funny and, in fact, funniest when presented with unbearable seriousness. I’d felt cornered in Southern California but in Manny’s company I began to understand that I had cornered myself. He was adept at describing grim episodes in his life—fateful indignities involving his painting career, his persistent lack of “success,” financial hardship, desperate labors in carpentry—and mining them for black comedy. And against all the dismal-ness and self-blame I could also see a fair share of luck, of work that paid off, achievements that were hard-won and absolute. At any rate, I pretty surely absorbed a variety of Manny’s mannerisms—his slow speed, his soft-spoken sarcasm, his protective coloring of self-deprecation—and have not quite managed to shake them.

It never occurred to me to sit in on his lectures—Manny never invited me, and besides, following the Effi Briest debacle, I had trouble imagining him in front of an audience. The aggressiveness of his prose, his freewheeling assertiveness, seemed to exist as a counterbalance to his hesitancy off the page. He scarcely even spoke about teach- ing, and I remember sitting in the car with him one afternoon, a parking lot rendezvous, awaiting the arrival of a young woman who showed up looking harried before handing off a cardboard box filled with graded exams. I had the impression, from the few words they exchanged, that the results were discouraging. Manny lifted the box’s lid, glancing in as if it contained poisonous snakes, then gingerly set the thing on the backseat.

In doing homework for this book, sifting through Manny’s papers, I found surviving notes, quizzes and exams displaying the depth of his pedagogical commitment, and they give the lie to the idea that he simply stopped writing after the last Farber-Patterson collaboration saw print in 1977. Even the briefest quizzes are dense, daunting, and fun, assuming a hyper-alertness to the interior workings of any given film. And later testimonials reveal that Manny was, in fact, an extraordinary lecturer, with Duncan Shepherd providing this definitive description:3

In 1981, at age 64, Manny was tagged an “Emergent American” when his paintings were selected for the Exxon National Exhibition, a group show at the Guggenheim Museum. He stayed with me in Manhattan, dodging a hotel bill while undoubtedly underestimating my ability to tolerate a certain level of bohemian squalor. (My midtown apartment was a former performance space, 2000 square feet, with a concrete floor and 200 metal folding chairs banked against one wall.) I had dropped out of college in slow motion, telling my parents I was taking time off but admitting to Manny that I’d had enough. I was convinced I had better things to do. We didn’t talk about it much; he was in town on business, caught up in the hope that the Guggenheim would provide a threshold leading to bigger things. I remember being mildly startled to see him in the morning, no longer wearing his usual black jeans and plaid shirt, transformed in a suit, vest and tie, an unlikely masquerade. It was like catching a familiar actor taking on a new and implausible role.

This was the period of Manny’s spectacular tondos, six feet in diameter. The scruffy, soft, loosely brushed background palette I’d admired earlier was exchanged for flat high- key colors. A sense of baroque energy and movement accompanied the expanded scale, reflecting notched-up industry and ambition. It didn’t escape me at the time: the termite had spread his wings and become Dumbo-esque. But there was nothing disheartening about this. I was primed to uphold a principled termite aesthetic, but even on my first acquaintance with the termite/elephant paradigm I felt Manny had set up a forced divi- sion between sensibilities that could, in fact, flow into one another like the two sides of a moebius strip. Some of the rangiest, most audacious artists that Manny talked and cared about—Agee, surely, and Welles, Jean Renoir, Godard, Fassbinder, Turner, Matisse—are shape-shifting experimenters, alternately humble and immodest, and can’t be categor- ically contained. Richard Thompson identified Manny’s true compass points, a set of shifty, process-oriented coordinates defined by “analogic rather than binary thought; a system which features complexity, simultaneity, and multiple positions.” Or, as JP Gorin put it: “Farber is not a dialectician but a pluralist. He produces contradictions and allows them to stand without leading to revision or resolution. Farber’s method is never one of ‘either/or’; he favors ‘and... and... and.’”4

From here, some backtracking may be helpful. Having slid out of school in the summer of 1980, I completed my first screenplay and (there was no direct correlation) found myself in the company of a Harvard graduate with a striking resemblance to Ali MacGraw. I wanted to show off the script and the girlfriend to Manny and Patricia. When the woman accompanied me to Southern California, we made a spontaneous road trip to San Diego where, with presumptuous last-minute-ness, I called Manny to tell him we were in town.

Patricia answered the phone and translated Manny’s response; he was too busy to see us. I was pressing, cajoling, importunate—but Manny was unbudgeable; we contented ourselves with a visit with one of their former students and drove back later that day.

Another thread in an unraveling story: at Harvard I’d shared a painting studio with a couple friends through the good graces of a house master who also departed from the school that same summer, a painter named Rob Storr. Rob, ten years older than me, was an exceptionally bright and eager talker about painting and politics, and I have fond memories of his work at the time: overhead views of inanimate objects scattered across desktops. I remember the meticulous authority with which he rendered the transparent plastic knobs on thumbtacks and their metal points. I showed him the compact Farber catalog, handsomely wrapped in brown paper, from Manny’s first retrospective (at the La Jolla Museum of Contemporary Art in 1978). I thought Rob might recognize an affinity, though Farber’s tabletops were distinctly more riotous and allusive than Storr’s. Rob of- fered a tart comment when he read the chronology at the back of the catalog, suggesting that the notes, plainly self-authored, reflected a forced effort to insert Farber, Zelig-like, in the center of New York intellectual life of the 1940s. No, I insisted, Manny was part of the scene; he was there.

I was scraping by in Manhattan, writing entries for a photography encyclopedia (a publication that never saw the light of day) while trying to find a way into the movie business, which, plainly enough, existed more fully on the opposite coast. At any rate, I was still in New York when Manny’s appearance at the Guggenheim led to his first solo show in Manhattan in almost a decade, at Richard Bellamy’s Oil and Steel gallery, a gathering of the Stationery and Auteur paintings in all their glory.

Delaying the inevitable attempt to knock on doors in L.A., following a few uncertain and impatient months, I took a train to Montana, determined to light out for the territories, see the true west. A novelist in Livingston invited me to visit his ranch, and a poet near the Wyoming border offered to take me fly fishing, but first I rented a car in Bozeman, leaning on a UCSD connection, a transplanted grad student named Elizabeth Guheen. (I wasn’t old enough to rent a vehicle on my own.) Elizabeth was the worried-looking TA delivering exams to Manny that distant afternoon. She let me crash on her couch and we stayed up late talking—about Manny, mainly, who exerted a gravitational pull from afar. She related a recent behind-the-scenes academic skirmish in which Manny defied consensus by refusing to allow that credits be given to a professor’s wife, a woman who hadn’t done the requisite school work but expected a passing grade. I remember Elizabeth’s spot-on imitation of Manny’s manner, his weary integrity and hesitation, repeating his rebuke to the group: “If we let her pass, then everything we’re doing here, is just...chickenshit.”

The faculty, Elizabeth reported, reversed themselves, yielded to Manny’s rectitude. The episode revealed a side of him I was glad to hear about.

We’re now approaching that part in the story where the guru thwacks the would-be disciple on the head with a sandal and says: “You idiot, I have nothing to teach you!” Or something close enough...

Following my Montana interlude, I landed back in California, hoping to secure an agent, and I wrote Manny an Agee-ish letter. I can’t remember a word of it, but it was undoubtedly pretentious, confiding my uncertainty, my impracticality, and my magnificent aspirations. I was in Long Beach, staying with my father, who was now separated from my mother—you can guess that things were getting complicated—when I paid the Farber-Patterson household another visit, in or around March of 1982, after a review of Manny’s New York show appeared in Art in America, a stinging assessment by Rob Storr—his first appearance in that magazine.5

Reviewing the review 36 years later, I’m struck by how thoroughgoing it is within the standard four-paragraph format, how perceptive, and how ungenerous. Rob recog- nizes that space in a Farber painting is both topographical and “the convoluted space projected by the mind’s eye.” This duality keys into an awareness that Farber, deploying toy objects and trains, is re-enacting “the private dramas of childhood” while composing pictures with the scene-setting sensibility of a filmmaker. But Storr gripes that Farber’s movie sources—Buñuel, Peckinpah—have a “toughness” that the paintings lack, and he condemns Farber’s color for “its tasteful intensity;” it’s not sufficiently “outrageous or evocative” and Storr regrets “the odd lack of feistiness in the paintings’ overall look”—all of this compared to the undeniable kick of Farber’s critical prose.6

The paintings, Rob concludes, leave “one feeling vaguely cheated.” As if to insist, simply and for all time, that Manny just couldn’t win, Rob winds up the piece with a hard slam: “We have been given the emblems and syntax of intelligent revery, but not the surprise of the dream itself.”

Intelligent revery. I now pause and think: What a fine description for a painting to fulfill. Who needs “the dream itself”?

At the dinner table with Manny and Patricia, at once defending and dismissing Rob’s review, my argument ran something like this: Give Rob a break, he’s just finding his way in the world. The paintings are terrific. You know this. It’s the work that counts; the work has to offer its own reward. Who cares about reviews?

I thought I was being encouraging and correct, but it was hardly a persuasive way to talk to a man who’d spent the better part of his life sweating blood manufacturing reviews. I was naïve, blind to the simple and occasionally crushing reality that reviews have consequences. And I was overlooking my complicity in the matter. Contra Out of the Past, I had not only failed to protect Manny from the lurking assassin, I had led the stranger straight to his door.

Manny took me aside after the meal and, vaguely referencing my letter, carefully muttering, with heavy pauses and little eye contact, let me know he was sensitive to the fact that I aimed to emulate Agee, but Manny wasn’t in the mood to be Father Flye (the mild, pious recipient of Agee’s earnest letters, written from boyhood onward and published in a posthumous book). For one thing, Manny explained, Father Flye was a square. Or rather, he was round and small, like his name. At any rate, Manny said, he had met Father Flye and he didn’t want to be my Father Flye. He was riffing, and even as my heart was sinking, recognizing that a part of my fragilely constructed identity was disintegrating, I was amazed by Manny’s default instinct to make stupid puns.

He recounted how pushy I’d been when trying to force a visit a few months back. He had nothing encouraging to say about my decision to exit school. And he revealed he’d been caught off guard when I turned up in Montana—Elizabeth had called Patricia and reported my visit; it must have seemed as if I were stalking him from afar. And now, this lethal little review in a big magazine...

We were in a dim room with a table lamp giving Manny’s head the high-contrast lighting that sculpted Brando’s lunar brow in Apocalypse Now. As he spoke, his hands were clutching his temple and his forehead as if holding up a cannonball whose weight was increasing with every sentence, and I was aware, in my own self-dramatizing way, of my apocalyptic disappointment, a free-falling feeling of rejection. He told me to cool it, he needed a break, I should keep my distance for a while, not forever, but for a couple months at least. I don’t remember the exact words, only that I was already withdrawing internally, backing away through a riptide of self-reproach. Why had I expected so much from him? Why lean on anyone, ever again, with such blind trust?

I stayed away, without anticipating or intending it, for about twelve years. I scored a Hollywood agent (quickly, against the odds) and embarked on a screenwriting career for a few lucrative seasons before directing my first feature, after which I moved back to New York. There were small signals of inter-communication and a kind of rapprochement when Brandeis University hosted a Farber retrospective in 1994. I attended the opening but we didn’t truly reconnect until I managed to make my first culturally respectable film, an adaptation of Hamlet released in 2000. I remember the almost cinematic drama of a pre-arranged phone call. I was on yet another train—heading to New Orleans but paused in Birmingham, Alabama—when I got out and found a pay phone near the plat- form. Patricia answered, amiable as ever, and passed the receiver to Manny, and I mainly remember the sight of the engine car vibrating in the heat and the distracting tension from feeding quarters into the phone as Manny’s slow dry voice, sounding unexpectedly chipper, traveled across the geographic distance and the raw emotional distance of the intervening years. He was registering approval, he liked the film, and the use of landscape, he told me, was strong and I should think about putting more landscape in my next movie. I explained that it was a city film; I’d made a conscious decision to limit the landscape to one scene—the graveyard scene—to score a point about the modern world. I realized I was speaking a bit too emphatically, as if to prove that I’d learned how to talk while having graduated, for better or worse, into a slightly more assured personality.

From that point on, with some regularity, I saw them whenever they came to New York. The path that circles the reservoir in Central Park, the lacquered halls and cramped rooms of the Hotel Wales, and the Wales lounge with a waxen female harp player seeming to move via animatronics—these settings are more vivid to me now than the content of our conversations. Manny, in his eighties, was less definably irascible. He was sharp, open, sweet-tempered, though also a bit unsteady, and slower than ever, with Patricia always near, reliably attentive. I prompted them to recall their early days in Manhattan: an apartment shared, in 1968, with a roommate who had a pet monkey named Gordon; and earlier, when they first, almost instantaneously moved in together, the unheated loft on Warren Street near City Hall. Manny would go out foraging in the winter, concealing a hacksaw within his overcoat, dismantling planks from police barricades to feed them into their stove. We could agree, now, that things were looking up.

Their last East Coast visits were occasioned by Manny’s “About Face” exhibition at PS1 in Queens, in September of 2004, a full retrospective initiated the previous year by the Museum of Contemporary Art in San Diego. At the opening Manny was surrounded by admirers—a palpable entourage, including a camera crew for a documentary portrait that has not been finished. He’d re-connected with Susan Sontag, and mentioned that he wished she could see the paintings and write about them. (But she was ill, and died that December.) For reasons outside my understanding, none of the usual Eastern publications reviewed or even acknowledged the show, a gradual source of hurt for Manny, despite the resounding sense of achievement. Rummaging online, I locate a detailed and sympathetic consideration that takes note of the “incredibly lush” color in his later pictures and offers that“the level of passion on display can be unsettling.”7 Curious, because I found the level of passion comforting. From what I could tell, the worst of Manny’s bitterness and anger had burned away, and what remained was a furious love of the world—the world out his window coalescing with the world in his head, art history converging with the contents of Patricia’s garden.

It became distinctly fun, when I found myself in L.A., to visit them in Leucadia, where their inner and outer lives seemed in complete harmony, at home in symmetrical studios and in the company of a kinetic black sheep dog named Annie. Amanda was now married and living close by, and I found it stirring to see her grown up, the mother of a luminous boy. The small square 1997 painting titled Raphael is not a nod to the Renaissance paint- er but to Manny’s newly arrived grandson, though around that time it became common for him to name pictures after painters: Between Bosch and Cézanne, Courbet’s Women, Carpaccio’s Dog, Caravaggio’s Last Supper, For Mondrian. The cultural bric-a-brac that swarmed through earlier pictures has been shoved to the side, while old masters are directly quoted—or nameless masters of Indian mogul painting and medieval icons, pictures plucked from art books as flowers and plants are plucked from the garden. In these late works—there was, of course, a conscious knowledge that they were late—the handling of paint is looser, slashed and scraped with a palette knife, and the color is warmer—daring and extravagant enough to impress Rob Storr’s younger self, I’d like to think. The pictures’ internal rhythms vary, but compositions still spill and sprawl. A few paintings, remarkably, reflect a measure of calm, but there’s also, almost always, some- thing ecstatic about these pictures. Sensuality becomes an explicit theme. Intelligent revery merges with celebratory dream.

You can reach a point, it’s occurred to me, where every loss or leave-taking, every career change or serious shift of focus can allow for a degree of recovery, continuity, growth. East Coast or West, White Elephant or Termite, success or failure—all the distinctions fold into a bigger picture, a more elusive whole accommodating a sense of mystery and (you have to hope) consolation. This, my memory tells me, is the spirit that hovered over our last conversations, walks in the local lagoon, and meals in the garden and inside the house.

The last time I saw Manny, in October 2007, Patricia drove us to a favored Italian restaurant off the 101, a highway that becomes humble as you approach San Diego, with palm trees and train tracks running parallel to traffic and the ocean a few blocks away. I remember him in the parking lot, in black jeans and a white button-down shirt with rolled sleeves, one hand fitted to his hip, the familiar stance. At 90, he seemed both frail and indestructible. The late autumn light made a kind of white flame of his hair, and this light followed us into the restaurant, igniting pumpkins on the counter and allowing Manny to notice, with apparent surprise, that my hair had caught fire like his. Over dinner, I talked about a Hollywood movie producer profiled in The New Yorker, a man who insisted that, within five minutes of meeting someone, he could tell you if that person was a winner or a loser. We grinned and laughed. I wondered, with their indulgence, how this kind of thinking had come to define American culture, American life, when such distinctions were plainly beside the point, success and failure being often as not, and in the long run, interchangeable and impossible. I may have been justifying my own precarious footing in the film business, or presumptuously making a case that we were all in the same flimsy boat. Later in the meal, foreshortening a casual speculation about the future, Manny said (not for the first time), “I’ll be dead soon,” and it wasn’t alarming to hear this, accompanied by his sweet smile. He had arrived at a sardonic approximation of serenity.

The last thing he said to me was “Don’t get old.” I told him I didn’t like the alternative. After he died—August 18, 2008—the wave of obituaries, recollections, and accolades left me feeling a little numb. I was taken aback by how abruptly and unilaterally he was granted admittance to the firmament of high achievers, how he was considered, now, a classic iconoclast, a “legendary” figure, a certified winner.8 His collected criticism, slated for publication by Harvard University Press, was claimed and carried aloft by the Library of America, shorn of a few dozen pieces on painting and other non-cinematic arts but upgraded, irresistibly, to canonical status before Agee and Kael were harvested in matching volumes. Reviews were fittingly over the moon.

Ten years later, Manny’s paintings remain less well-known, less assuredly loved. Thus, this book. Which happens to comes after Helen Molesworth’s inspired group exhibition at L.A.MOCA,“One Day at a Time: Manny Farber and Termite Art,” in which Farber figures as a heroic pioneer, leading the way for a bracingly wide assortment of younger artists of variegated backgrounds, media and methods. To read through Molesworth’s catalogue is to witness an astonishing apotheosis: the sour and self-effacing termite saint rising through the floorboards to make imperishable marks on another era, the immediate present, and infinite days to come. I picture Manny gripping his brow in amazement and mock-misery.

Allow me a final flashback. While Manny lay in hospice in the converted back room adjoining his studio, Robert Walsh called to let me know it was my last chance to say good-bye if I had any intention of doing so. Robert described how Manny was unable to talk but intermittently conscious, at one point extending his arms, pushing his hands through space, making jabbing gestures as if swimming or, Robert realized, painting. I flew from New York, arriving in Leucadia the morning after Manny died, and was welcomed into the house by Patricia. She had slept in bed beside him one last time and had just reported the death. She seemed to take it for granted that I’d want time with the body, and left me alone with him with the door closed.

He was lying on his back, wearing a T-shirt, one arm lifted across his stomach, his other arm straight and slack at his side, a sheet covering his body below his chest, his head on a pillow, uptilted, eyes closed, mouth not quite closed, his face looking carved, almost calm but also, in fact, rather fierce, rigid, defiant. It would take a few thousand words to retrace the paths traveled by my mind confronting this presence, this absence. Suffice it to say my thoughts were like pennies in a Bendix or, more accurately, like objects, colors, and words scattered across a Manny Farber painting. After about fifteen minutes—after he failed to sit up and ask me to leave —I brought out a piece of paper and carefully drew his face, a simple line drawing that I’ve never shared with anyone. When a person has had an incalculable effect on your life, there are many ways to say good-bye. Saying good-bye, for that matter, becomes a relentlessly extended process, as enthralling as it is confusing. Actually, I’ve been learning, it never really stops.

We met in 1976, when I was 16 or 17; Manny was 59. I’d bicycled to Orange Coast Community College to see him present Fassbinder’s Effi Briest. Manny brought the movie with him, the actual film reels, but got lost on the freeway and arrived more than an hour late. When he began his introduction, the auditorium lights dimmed and the projector flashed on, beaming onto his face. He tried talking, a startled sentence or two, and I felt I was catching a guest appearance by Professor Irwin Corey, the shambling, comic TV authority with wild eyes and windblown hair, one pedantic finger held high before declaring: “However...” Then Manny stepped out of the light—the stark equivalent of a vaudeville hook yanking him offstage.

Effi Briest is one of Fassbinder’s most beautifully measured, austere films, black- and-white, two hours and 15 minutes long. Manny never wrote about it, and I don’t remember the post-screening Q&A, only that it was brief, as the movie had run past midnight and the wearied audience was invited to disperse. I intercepted Manny outside, told him I’d just read his book and asked if he could talk about James Agee. Manny stared, then offered, in his quiet dry voice: “He was handsome as hell.” Realizing this was perhaps inadequate, he added, “He was heroic.” Then he said, “It’s late. Come to San Diego some time and we can talk.”

He must have supplied me with a phone number, and I must have called. I don’t remember the particulars, but within weeks I was on Amtrak’s Pacific Surfliner, shuttling past the orange groves of San Clemente, the white spheres of the San Onofre nuclear power plant and then, for a sustained stretch, the glittering ocean. Arriving in Del Mar, I was picked up by a student and ferried to Manny’s studio on the UCSD campus.

The jacket flap of Negative Space described its author as “a noted painter,” but his paintings were wholly new to me and I spent a lot of time, on that first visit, roaming around the studio, looking closely, nearly mute. The pale, slashed, scuffed color, and the way objects were given hard edges and outlines, reminded me of Degas, though Degas never got around to painting still lifes. I told Manny this. He didn’t seem displeased.

He hadn’t quite declared his retirement from film criticism, but writing, he insisted, was “killing” and “brutal,” whereas painting, plainly enough, seemed to yield actual pleasure. In the calm of his studio, the nutty professor image gave way to a more stalwart impression. You know from photographs that Manny was vivid—the deepset eyes, sharp nose, domelike brow—though photos don’t quite capture his deadpan charm, his air of antic irascibility or plain mischief. He had the body of an athlete, a workman: narrow hips, powerful arms. There was something rueful and shy in his bearing, but also a forthright- ness, a centeredness. It was common to see him holding a cowboy stance, one hand to his hip, his square tipped fingers slightly splayed—each finger broken, he’d tell you, in the course of carpentry jobs—and his head slightly tilted, a smile softening the lines of his face. He often seemed abashed, easily bewildered, and would fall into another pose while seated: his fingers would crawl up along his cranium, and stay near the top, sheltering and hiding his face. It was a kind of comic illustration of abject “thinking,” and he’d wake from it, or shrug it off, with sudden vivacity, a wisecrack, that smile.

Maybe shyness was our basic common ground. I was, I should explain, an introverted, saturnine kid, a reluctant teenager who preferred the company of adults. My one identifiable talent as a boy was for drawing and, by extension, painting, but my confidence in this way of understanding the world had been rattled when my family moved to California, transporting me, unconsulted, from the pastoral suburbs (as I remembered them) of Overland Park, Kansas to the synthetic paradise of Costa Mesa, where our new house seemed to have emanated from the adjacent golf course. I met Manny during my tormented fourth year of non-adjustment.

I was—need I elaborate?—odd, friendless; I hated school, spent lunch hours in the library, refused to be photographed, scarcely spoke. But I had started watching a lot of old movies—L.A. TV stations showed them all the time; the air, it seemed, was thick with movies—and I had fixed on James Agee, dead before I was born, as a ghostly patron saint, a suitably high-minded and self-destructive role model. I’d read all the Agee in print, and I wanted to project myself into a future where I’d make the kind of movies Agee proselytized for in his reviews and scripts, a notion of movie poetry distilled from the grain of documentary fact. I had a dim awareness that this was preposterous, but the idea was too absorbing to let go of.

And Manny, on some level, must have been sympathetic. Negative Space, after all, opens with a 1957 piece,“UndergroundFilms,”pretty much a precursor to arguments refined and flung around six years later in the gradually famous Termite Art essay. Agee is given pride of place when Manny veers off in the middle, announcing a fascinatingly mismatched private pantheon:

However, any day now, Americans may realize that scrambling after the obvious in art is a losing game. The sharpest work of the last thirty years is to be found by studying the most unlikely, self-destroying, uncompromising, roundabout artists. When the day comes for praising infamous men of art, some great talent will be shown in true light: people like Weldon Kees, the rangy Margie Israel, James Agee, Isaac Rosenfeld, Otis Ferguson, Val Lewton, a dozen comic-strip geniuses like the creator of “Harold Teen,” and finally a half-dozen directors such as the master of the ambulance, speedboat, flying-saucer movie: Howard Hawks.

(It’s curious to note, decades down the line, that half the listed names are still altogether obscure.)

“I liked him more than that,” Manny conceded, with real contrition, when I mentioned “Nearer My Agee to Thee,” his direct assessment of Agee’s posthumously collected film criticism, written as if to hold off an avalanche of misjudged Agee hero-worship. It’s a fairly caustic, corrosive piece in which affection is crowded out by mockery, dumb puns on Agee’s name, accusations of grandstanding and glibness. Agee’s “superabundant writing talent” and the “excessive richness” of his reviews are found wanting after Manny factors in Agee’s effortful moralizing and his supplication to “Big Art,” which allowed Agee to miss the value of “super-present-tense material” in the more modest movies Manny prized and praised. In the thick of it, Manny rates one of Agee’s finest virtues to be “a way of playing leapfrog with clichés, making them sparkle like pennies lost in a Bendix.” Even when I first read it, I marveled at this sentence. Who in the world would conjure this chain of associations—clichés, frogs, pennies in a washing machine—and find those words to pin them down? Why be so crazily precise in marrying physical description to abstract attributes? The language skates on the edge of sheer silliness. Decades later, Manny took up the same tack in his paintings, where leapfrogging clichés, in the form of toys and trains, tumble across tabletop arrangements to invoke his favorite films and the contradictory ingredients spilling in and out of them.

At any rate, Manny, that morning, was game to talk about Agee’s gift for talk, but also about how he’d sit silent when riding on a train, staring out the window, his face held close to the glass. Manny didn’t bother mentioning his friend’s drinking or womanizing, highlighted in a biography published just a few years later.1 But he remembered his generosity, his unstoppableness, during their would-be collaboration, a screenplay idea instigated by Agee—a romance framed by 24 hours like Minnelli’s The Clock. They sat side by side on a park bench and talked it through; or rather Agee talked, describing scenes in impossible detail while Manny listened, overwhelmed. “He was too smart for me,” was the glum summary. (Years later, Robert Walsh presented me with the unearthed, uncompleted manuscript for the project; Agee’s penciled writing was incredibly tiny, clotted and crabbed, smeared into the paper—an illegible fog.)

I met Patricia—she probably joined us for lunch—though it’s hard to separate my first impression from the abiding picture developed over time. She was warm, watchful, unassertive, mild, alert. Her softness stood in sharp contrast to his gruffness. She had a different grade or degree of shyness. I thought she was lovely and mysterious in the way that women hovering in the middle distance of Vuillard paintings are lovely and mysterious—to name one of her conspicuous influences at that time. It was easy to recognize that Manny was lucky to have her in his corner, and he was sensible enough to acknowledge his luck, though it tended to be channeled through praise for her work, muttered matter-of-factly and with a tinge of awe. “Patricia’s paintings are terrific. Look at the way she gets that line. It kills me.” Sure enough, I was at least as impressed with what she was up to in her canvases; it was closer to what I would have been doing if I kept painting, and what, in fact, I dabbled at later. The faded color snapshots from Patricia’s time spent on the Aran Islands were scattered about her studio, so you saw the paintings’ undisguised sources and could track the process of distillation, the assurance of her drawing, her eye for pattern and color, the airy quality of light within the paint.

I wanted to know about New York in the 40s and 50s, the Cedar Tavern crowd. Patricia and I listened like children as Manny admitted getting into a fist fight with Jackson Pollock, a lousy fighter, he was surprised to discover, and with Clement Greenberg, who was unexpectedly tough. The scuffle with Pollock somehow involved a bathroom door; the source of the dispute was lost in time. But the brawl with Greenberg, he remembered, was about Henry James. What about Henry James, I asked, with more than a little curiosity. That he could not remember.

I was invited back to Del Mar, and stayed the night, slept on the couch, shared breakfast. Within the year, they moved to Leucadia, to the house Manny died in 40 years later, a compact structure amidst rows of commercial greenhouses, less than five minutes from the beach. Over the next three years, my visits became something of a routine, a reassuring and reliable escape from other contexts and frames. While still officially a high school student, I was allowed to take classes at UC Irvine—a bowl-shaped campus constructed like a futuristic frontier town, bordered by dusty hills; Manny knew it and described how the students “roll around like marbles” along the intersecting paths. I became one of the marbles and, following Manny’s recommendation, took art history classes taught by Phil Leider, his former editor at Artforum, a spring-heeled pacer, explicator, and aphorist whose crowd-pleasing lecturing style seemed like a mashup of Manny Farber and Lenny Bruce. (Lucas Cranach’s mincing nudes, with their arabesquing backs, were compared to spirochetes. Picasso was “the last great artist whose life was kissed by God.” And so on.)

I was introduced to the inner circle of UCSD colleagues: Jean-Pierre Gorin, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Duncan Shepherd, and a few grad students closer to my age. I noticed that almost all Farber associates picked up a vocabulary for talking about movies in terms of “terrain” and “territory” while adopting hand gestures, consciously or not, that mirrored Manny’s, holding an index finger aloft, projecting it down a short vector, as if tracing a track on an imaginary map. And, spending time with Manny, it was nearly impossible to not take on his appreciation of the local landscape: the hectic Seuss-like foliage scamp- ering near and far across surrounding cliffs, bluffs, and arroyos. (Dr. Seuss, I learned, lived nearby; the man was simply reporting on what he saw outside his window and in his backyard, as Manny came to do. The La Jolla post office had to hire extra carriers to deliver the Doctor’s mail on his birthday. Surely, Dr. Seuss was the last great artist whose life was kissed by God.)

Manny thought it might be beneficial for me to meet his once-estranged daughter, Amanda, who was two years older than me, in the process of a hard-won realignment with her father. I remember a pale intense young woman, raven-haired, with big brown eyes and a disarming smile. The smile flashed when she talked about Werner Herzog’s offer to cast Manny in Stroszek, Herzog’s first American film, in which Manny would play a tractor-driving farmer, and Amanda the farmer’s daughter. I remember Manny’s furrowed brow and his simple certainty when he told me he turned Herzog down, avoiding potential glory and/or humiliation.

I graduated high school, just barely, on the strength of transferred UCI credits, and when I went east to Harvard (still looking for Agee, who was nowhere to be found) I studied art history, though none of my teachers measured up to Phil Leider. Visiting with Manny and Patricia during school breaks, I could talk with tolerable earnestness and detail about Piero della Francesca, George Stubbs, Cézanne, Matisse, Turner, Ruskin, Adrian Stokes, Goya, Robert Smithson, Leo Steinberg. These, as I remember it, were the painters and writers up for discussion. We also talked about Preston Sturges, Nick Ray and Nic Roeg, Robert Bresson, Orson Welles (especially Touch of Evil, which we all loved), and the New German Cinema. It was easy to agree, when the subject came up, that movie criticism was at a low ebb, that film reviewers had become dispensers of consumer reports, guys on TV wearing sweaters. (That said, by this time Roger Ebert had become Manny’s loyal friend and champion when they met up in festivals in Telluride and Venice.)

What did I have to offer them? Why did Manny and Patricia, after a fashion, adopt me? The questions hum in my head at this long distance, decades down the road. Jonathan Rosenbaum, in a 1994 essay he considers one of the best things he’s ever written,2 recounts in considerable detail his troubled year as Manny’s recruit in the UCSD film department, where he found himself in helpless competition with Jean-Pierre Gorin. Recognizing similarities in their childhoods, the presence of over-achieving brothers in both the Farber and Rosenbaum households, Jonathan concludes that the theme of his essay is sibling rivalry, while also noting that Manny, presiding over a variety of faculty members and students, had a talent for enticing younger men into imbalanced father-son relationships. In Routine Pleasures, Gorin’s multi-faceted documentary essay shot in 1985, you get an equally acute Farber portrait, though pointedly oblique, shaped around Manny’s absence since he declined, once again, to be filmed. Puttering model train enthusiasts in Del Mar serve as Farber surrogates, and two intricate Farber paintings get star treatment as Babette Mangolte’s camera glides across and inside them. (The paintings hold the screen with great verve.) But JP (as I came to know him) circles around Farber, the elusive curmudgeon, with speculative voice-over, commentary, and quips. At one point he admits: “It made for a story that all the shrinks in the audience would read as a search for the father, but which I kept seeing as an old-fashioned buddy story.” I could say something similar. During those years, I was pretty good at deflecting the thought that I was looking for a father figure in Manny, preferring to think of myself as a stand-in for the steadfast deaf-mute kid in Out of the Past, the resourceful sidekick who sticks close to Robert Mitchum and, you know, rescues him from a smug assassin with the deft tug of a fishing line. As far as I could tell, I’d won Manny’s approval by being near-silent and selfless, and by awarding his work my purist attention. Reading Manny and Patricia’s career-capping interview in Film Comment, I flattered myself with a private beam of identification when Manny singled out Jean-Luc Godard at the end of the piece:

The Straubs walked through my studio as though they were looking at measles. [...] Franju did it as if he were looking at nothing. [...] The only one who ever reacted the right way is Godard, of all the movie people who have been through here, including Scorsese and Schrader and De Palma. Godard sat down and looked at one abstract picture without saying a word for ten minutes, even though we were late for his lecture.

I clocked a good deal of time in Manny’s studio, and accompanied him on errands, moving through shimmering parking lots as he groused, joked, and misplaced his car. I can recognize now what I dimly intuited at the time: I had a need to find in Manny’s presence, his example, and his implicit or outright guidance, both a fortification of my own awkwardness and multiple ways to escape it. I was drawn to his irreverence and his humility, his intransigence and his deadpan comic timing, his contempt for “corny” sentimentality and his suspicion that things are funny and, in fact, funniest when presented with unbearable seriousness. I’d felt cornered in Southern California but in Manny’s company I began to understand that I had cornered myself. He was adept at describing grim episodes in his life—fateful indignities involving his painting career, his persistent lack of “success,” financial hardship, desperate labors in carpentry—and mining them for black comedy. And against all the dismal-ness and self-blame I could also see a fair share of luck, of work that paid off, achievements that were hard-won and absolute. At any rate, I pretty surely absorbed a variety of Manny’s mannerisms—his slow speed, his soft-spoken sarcasm, his protective coloring of self-deprecation—and have not quite managed to shake them.

It never occurred to me to sit in on his lectures—Manny never invited me, and besides, following the Effi Briest debacle, I had trouble imagining him in front of an audience. The aggressiveness of his prose, his freewheeling assertiveness, seemed to exist as a counterbalance to his hesitancy off the page. He scarcely even spoke about teach- ing, and I remember sitting in the car with him one afternoon, a parking lot rendezvous, awaiting the arrival of a young woman who showed up looking harried before handing off a cardboard box filled with graded exams. I had the impression, from the few words they exchanged, that the results were discouraging. Manny lifted the box’s lid, glancing in as if it contained poisonous snakes, then gingerly set the thing on the backseat.

In doing homework for this book, sifting through Manny’s papers, I found surviving notes, quizzes and exams displaying the depth of his pedagogical commitment, and they give the lie to the idea that he simply stopped writing after the last Farber-Patterson collaboration saw print in 1977. Even the briefest quizzes are dense, daunting, and fun, assuming a hyper-alertness to the interior workings of any given film. And later testimonials reveal that Manny was, in fact, an extraordinary lecturer, with Duncan Shepherd providing this definitive description:3

It seems feeble and formulaic to call him a brilliant, an illuminating, a stimulating, an inspiring teacher. It wasn’t necessarily what he had to say (he was prone to shrug off his most searching analysis as “gobbledygook”) so much as it was the whole way he went about things, famously showing films in pieces, switching back and forth from one film to another, ranging from Griffith to Godard, Bugs Bunny to Yasujiro Ozu, talking over them with or without sound, running them backwards through the projector, mixing in slides of paintings, sketching out compositions on the blackboard, the better to assist students in seeing what was in front of their faces, to wean them from Plot, Story, What Happens Next, and to disabuse them of the absurd notion that a film is all of a piece, all on a level, quantifiable, rankable, fileable....It was always about looking and seeing.

In 1981, at age 64, Manny was tagged an “Emergent American” when his paintings were selected for the Exxon National Exhibition, a group show at the Guggenheim Museum. He stayed with me in Manhattan, dodging a hotel bill while undoubtedly underestimating my ability to tolerate a certain level of bohemian squalor. (My midtown apartment was a former performance space, 2000 square feet, with a concrete floor and 200 metal folding chairs banked against one wall.) I had dropped out of college in slow motion, telling my parents I was taking time off but admitting to Manny that I’d had enough. I was convinced I had better things to do. We didn’t talk about it much; he was in town on business, caught up in the hope that the Guggenheim would provide a threshold leading to bigger things. I remember being mildly startled to see him in the morning, no longer wearing his usual black jeans and plaid shirt, transformed in a suit, vest and tie, an unlikely masquerade. It was like catching a familiar actor taking on a new and implausible role.

This was the period of Manny’s spectacular tondos, six feet in diameter. The scruffy, soft, loosely brushed background palette I’d admired earlier was exchanged for flat high- key colors. A sense of baroque energy and movement accompanied the expanded scale, reflecting notched-up industry and ambition. It didn’t escape me at the time: the termite had spread his wings and become Dumbo-esque. But there was nothing disheartening about this. I was primed to uphold a principled termite aesthetic, but even on my first acquaintance with the termite/elephant paradigm I felt Manny had set up a forced divi- sion between sensibilities that could, in fact, flow into one another like the two sides of a moebius strip. Some of the rangiest, most audacious artists that Manny talked and cared about—Agee, surely, and Welles, Jean Renoir, Godard, Fassbinder, Turner, Matisse—are shape-shifting experimenters, alternately humble and immodest, and can’t be categor- ically contained. Richard Thompson identified Manny’s true compass points, a set of shifty, process-oriented coordinates defined by “analogic rather than binary thought; a system which features complexity, simultaneity, and multiple positions.” Or, as JP Gorin put it: “Farber is not a dialectician but a pluralist. He produces contradictions and allows them to stand without leading to revision or resolution. Farber’s method is never one of ‘either/or’; he favors ‘and... and... and.’”4

From here, some backtracking may be helpful. Having slid out of school in the summer of 1980, I completed my first screenplay and (there was no direct correlation) found myself in the company of a Harvard graduate with a striking resemblance to Ali MacGraw. I wanted to show off the script and the girlfriend to Manny and Patricia. When the woman accompanied me to Southern California, we made a spontaneous road trip to San Diego where, with presumptuous last-minute-ness, I called Manny to tell him we were in town.

Patricia answered the phone and translated Manny’s response; he was too busy to see us. I was pressing, cajoling, importunate—but Manny was unbudgeable; we contented ourselves with a visit with one of their former students and drove back later that day.

Another thread in an unraveling story: at Harvard I’d shared a painting studio with a couple friends through the good graces of a house master who also departed from the school that same summer, a painter named Rob Storr. Rob, ten years older than me, was an exceptionally bright and eager talker about painting and politics, and I have fond memories of his work at the time: overhead views of inanimate objects scattered across desktops. I remember the meticulous authority with which he rendered the transparent plastic knobs on thumbtacks and their metal points. I showed him the compact Farber catalog, handsomely wrapped in brown paper, from Manny’s first retrospective (at the La Jolla Museum of Contemporary Art in 1978). I thought Rob might recognize an affinity, though Farber’s tabletops were distinctly more riotous and allusive than Storr’s. Rob of- fered a tart comment when he read the chronology at the back of the catalog, suggesting that the notes, plainly self-authored, reflected a forced effort to insert Farber, Zelig-like, in the center of New York intellectual life of the 1940s. No, I insisted, Manny was part of the scene; he was there.

I was scraping by in Manhattan, writing entries for a photography encyclopedia (a publication that never saw the light of day) while trying to find a way into the movie business, which, plainly enough, existed more fully on the opposite coast. At any rate, I was still in New York when Manny’s appearance at the Guggenheim led to his first solo show in Manhattan in almost a decade, at Richard Bellamy’s Oil and Steel gallery, a gathering of the Stationery and Auteur paintings in all their glory.

Delaying the inevitable attempt to knock on doors in L.A., following a few uncertain and impatient months, I took a train to Montana, determined to light out for the territories, see the true west. A novelist in Livingston invited me to visit his ranch, and a poet near the Wyoming border offered to take me fly fishing, but first I rented a car in Bozeman, leaning on a UCSD connection, a transplanted grad student named Elizabeth Guheen. (I wasn’t old enough to rent a vehicle on my own.) Elizabeth was the worried-looking TA delivering exams to Manny that distant afternoon. She let me crash on her couch and we stayed up late talking—about Manny, mainly, who exerted a gravitational pull from afar. She related a recent behind-the-scenes academic skirmish in which Manny defied consensus by refusing to allow that credits be given to a professor’s wife, a woman who hadn’t done the requisite school work but expected a passing grade. I remember Elizabeth’s spot-on imitation of Manny’s manner, his weary integrity and hesitation, repeating his rebuke to the group: “If we let her pass, then everything we’re doing here, is just...chickenshit.”

The faculty, Elizabeth reported, reversed themselves, yielded to Manny’s rectitude. The episode revealed a side of him I was glad to hear about.

We’re now approaching that part in the story where the guru thwacks the would-be disciple on the head with a sandal and says: “You idiot, I have nothing to teach you!” Or something close enough...

Following my Montana interlude, I landed back in California, hoping to secure an agent, and I wrote Manny an Agee-ish letter. I can’t remember a word of it, but it was undoubtedly pretentious, confiding my uncertainty, my impracticality, and my magnificent aspirations. I was in Long Beach, staying with my father, who was now separated from my mother—you can guess that things were getting complicated—when I paid the Farber-Patterson household another visit, in or around March of 1982, after a review of Manny’s New York show appeared in Art in America, a stinging assessment by Rob Storr—his first appearance in that magazine.5

Reviewing the review 36 years later, I’m struck by how thoroughgoing it is within the standard four-paragraph format, how perceptive, and how ungenerous. Rob recog- nizes that space in a Farber painting is both topographical and “the convoluted space projected by the mind’s eye.” This duality keys into an awareness that Farber, deploying toy objects and trains, is re-enacting “the private dramas of childhood” while composing pictures with the scene-setting sensibility of a filmmaker. But Storr gripes that Farber’s movie sources—Buñuel, Peckinpah—have a “toughness” that the paintings lack, and he condemns Farber’s color for “its tasteful intensity;” it’s not sufficiently “outrageous or evocative” and Storr regrets “the odd lack of feistiness in the paintings’ overall look”—all of this compared to the undeniable kick of Farber’s critical prose.6

The paintings, Rob concludes, leave “one feeling vaguely cheated.” As if to insist, simply and for all time, that Manny just couldn’t win, Rob winds up the piece with a hard slam: “We have been given the emblems and syntax of intelligent revery, but not the surprise of the dream itself.”

Intelligent revery. I now pause and think: What a fine description for a painting to fulfill. Who needs “the dream itself”?

At the dinner table with Manny and Patricia, at once defending and dismissing Rob’s review, my argument ran something like this: Give Rob a break, he’s just finding his way in the world. The paintings are terrific. You know this. It’s the work that counts; the work has to offer its own reward. Who cares about reviews?

I thought I was being encouraging and correct, but it was hardly a persuasive way to talk to a man who’d spent the better part of his life sweating blood manufacturing reviews. I was naïve, blind to the simple and occasionally crushing reality that reviews have consequences. And I was overlooking my complicity in the matter. Contra Out of the Past, I had not only failed to protect Manny from the lurking assassin, I had led the stranger straight to his door.

Manny took me aside after the meal and, vaguely referencing my letter, carefully muttering, with heavy pauses and little eye contact, let me know he was sensitive to the fact that I aimed to emulate Agee, but Manny wasn’t in the mood to be Father Flye (the mild, pious recipient of Agee’s earnest letters, written from boyhood onward and published in a posthumous book). For one thing, Manny explained, Father Flye was a square. Or rather, he was round and small, like his name. At any rate, Manny said, he had met Father Flye and he didn’t want to be my Father Flye. He was riffing, and even as my heart was sinking, recognizing that a part of my fragilely constructed identity was disintegrating, I was amazed by Manny’s default instinct to make stupid puns.

He recounted how pushy I’d been when trying to force a visit a few months back. He had nothing encouraging to say about my decision to exit school. And he revealed he’d been caught off guard when I turned up in Montana—Elizabeth had called Patricia and reported my visit; it must have seemed as if I were stalking him from afar. And now, this lethal little review in a big magazine...

We were in a dim room with a table lamp giving Manny’s head the high-contrast lighting that sculpted Brando’s lunar brow in Apocalypse Now. As he spoke, his hands were clutching his temple and his forehead as if holding up a cannonball whose weight was increasing with every sentence, and I was aware, in my own self-dramatizing way, of my apocalyptic disappointment, a free-falling feeling of rejection. He told me to cool it, he needed a break, I should keep my distance for a while, not forever, but for a couple months at least. I don’t remember the exact words, only that I was already withdrawing internally, backing away through a riptide of self-reproach. Why had I expected so much from him? Why lean on anyone, ever again, with such blind trust?

I stayed away, without anticipating or intending it, for about twelve years. I scored a Hollywood agent (quickly, against the odds) and embarked on a screenwriting career for a few lucrative seasons before directing my first feature, after which I moved back to New York. There were small signals of inter-communication and a kind of rapprochement when Brandeis University hosted a Farber retrospective in 1994. I attended the opening but we didn’t truly reconnect until I managed to make my first culturally respectable film, an adaptation of Hamlet released in 2000. I remember the almost cinematic drama of a pre-arranged phone call. I was on yet another train—heading to New Orleans but paused in Birmingham, Alabama—when I got out and found a pay phone near the plat- form. Patricia answered, amiable as ever, and passed the receiver to Manny, and I mainly remember the sight of the engine car vibrating in the heat and the distracting tension from feeding quarters into the phone as Manny’s slow dry voice, sounding unexpectedly chipper, traveled across the geographic distance and the raw emotional distance of the intervening years. He was registering approval, he liked the film, and the use of landscape, he told me, was strong and I should think about putting more landscape in my next movie. I explained that it was a city film; I’d made a conscious decision to limit the landscape to one scene—the graveyard scene—to score a point about the modern world. I realized I was speaking a bit too emphatically, as if to prove that I’d learned how to talk while having graduated, for better or worse, into a slightly more assured personality.

From that point on, with some regularity, I saw them whenever they came to New York. The path that circles the reservoir in Central Park, the lacquered halls and cramped rooms of the Hotel Wales, and the Wales lounge with a waxen female harp player seeming to move via animatronics—these settings are more vivid to me now than the content of our conversations. Manny, in his eighties, was less definably irascible. He was sharp, open, sweet-tempered, though also a bit unsteady, and slower than ever, with Patricia always near, reliably attentive. I prompted them to recall their early days in Manhattan: an apartment shared, in 1968, with a roommate who had a pet monkey named Gordon; and earlier, when they first, almost instantaneously moved in together, the unheated loft on Warren Street near City Hall. Manny would go out foraging in the winter, concealing a hacksaw within his overcoat, dismantling planks from police barricades to feed them into their stove. We could agree, now, that things were looking up.

Their last East Coast visits were occasioned by Manny’s “About Face” exhibition at PS1 in Queens, in September of 2004, a full retrospective initiated the previous year by the Museum of Contemporary Art in San Diego. At the opening Manny was surrounded by admirers—a palpable entourage, including a camera crew for a documentary portrait that has not been finished. He’d re-connected with Susan Sontag, and mentioned that he wished she could see the paintings and write about them. (But she was ill, and died that December.) For reasons outside my understanding, none of the usual Eastern publications reviewed or even acknowledged the show, a gradual source of hurt for Manny, despite the resounding sense of achievement. Rummaging online, I locate a detailed and sympathetic consideration that takes note of the “incredibly lush” color in his later pictures and offers that“the level of passion on display can be unsettling.”7 Curious, because I found the level of passion comforting. From what I could tell, the worst of Manny’s bitterness and anger had burned away, and what remained was a furious love of the world—the world out his window coalescing with the world in his head, art history converging with the contents of Patricia’s garden.

It became distinctly fun, when I found myself in L.A., to visit them in Leucadia, where their inner and outer lives seemed in complete harmony, at home in symmetrical studios and in the company of a kinetic black sheep dog named Annie. Amanda was now married and living close by, and I found it stirring to see her grown up, the mother of a luminous boy. The small square 1997 painting titled Raphael is not a nod to the Renaissance paint- er but to Manny’s newly arrived grandson, though around that time it became common for him to name pictures after painters: Between Bosch and Cézanne, Courbet’s Women, Carpaccio’s Dog, Caravaggio’s Last Supper, For Mondrian. The cultural bric-a-brac that swarmed through earlier pictures has been shoved to the side, while old masters are directly quoted—or nameless masters of Indian mogul painting and medieval icons, pictures plucked from art books as flowers and plants are plucked from the garden. In these late works—there was, of course, a conscious knowledge that they were late—the handling of paint is looser, slashed and scraped with a palette knife, and the color is warmer—daring and extravagant enough to impress Rob Storr’s younger self, I’d like to think. The pictures’ internal rhythms vary, but compositions still spill and sprawl. A few paintings, remarkably, reflect a measure of calm, but there’s also, almost always, some- thing ecstatic about these pictures. Sensuality becomes an explicit theme. Intelligent revery merges with celebratory dream.

You can reach a point, it’s occurred to me, where every loss or leave-taking, every career change or serious shift of focus can allow for a degree of recovery, continuity, growth. East Coast or West, White Elephant or Termite, success or failure—all the distinctions fold into a bigger picture, a more elusive whole accommodating a sense of mystery and (you have to hope) consolation. This, my memory tells me, is the spirit that hovered over our last conversations, walks in the local lagoon, and meals in the garden and inside the house.