Mark McGURL

GENERIC LOVE

or

THE REALISM

OF ROMANCE

(THE CONSUMER

AS HERO)

GENERIC LOVE

or

THE REALISM

OF ROMANCE

(THE CONSUMER

AS HERO)

An excerpt from a book called

EVERYTHING & LESS:

THE NOVEL IN THE

AGE OF AMAZON

As the story goes, Jeff BEZOS left a lucrative job to start something new in Seattle after being deeply affected by Kazuo ISHIGURO’s REMAINS OF THE DAY. If a novel gave us AMAZON, what has Amazon meant for the novel? In EVERYTHING & LESS—published by Verso—acclaimed critic Mark McGURL discovers a dynamic scene of cultural experimentation in literature. Its innovations have little to do with how the novel is written and more to do with how it’s distributed online. On the internet, all fiction becomes genre fiction, which is simply another way to predict customer satisfaction.

With an eye on the longer history of the novel, this witty, acerbic book tells a story that connects Henry JAMES to E. L. JAMES, and FAULKNER and HEMINGWAY to contemporary romance, science fiction and fantasy writers. Reclaiming several works of self-published fiction from the gutter of complete critical disregard, it stages a copernican revolution in how we understand the world of letters: it’s the stuff of high literature—Colson WHITEHEAD, Don DeLILLO and Amitav GHOSH—that revolves around the star of countless unknown writers trying to forge a career by untraditional means, adult baby diaper lover erotica being just one fortuitous route. In opening the floodgates of popular literary expression as never before, the age of AMAZON shows a democratic promise, as well as what it means when literary culture becomes corporate culture in the broadbest but also deepest and most troubling sense.

ORDER THE

BOOK DIRECT

FROM THE

PUBLISHER HERE ...

What does the rise of Amazon to a dominant position in the landscape of contemporary bookselling teach us about the place of the novel in contemporary life? Above all, it forces a reckoning with the novel’s identity—even in its most artistically ambitious or “literary” instances—as a commodity, as something bought and sold. This reckoning takes many forms in my new book, including, perhaps most importantly, a reconsideration of genre distinctions as a type of product differentiation and market segmentation specific to the literary field. Relatedly, I argue that there is a new quality of “generic-ness” in so many of the highly esteemed novels we read, not just in those we label “genre fiction.”

A great example would be the works of Sally Rooney, whom their author does not shy away from describing as romance novels. This has not kept them from being read and discussed by large swatches of the international literary intelligentsia. Rooney’s romances are in some ways highly discordant with the romance genre in its most popular form, where the hero is a figure above all of decision, of the abolishment of doubt. Her heroes are beset with doubts, as are her heroines. The constitutive confusion about the meaning of intimacy for modern youth is never denied in Conversations with Friends (2017) or Normal People (2018) or Beautiful World, Where Are You (2021) the way it is in mass market romance.

And yet, no one could miss the easy-going, even ingratiating quality of her prose, which for all its intelligence is not unduly demanding. The situations it so convincingly describes feed our desire for intimate knowledge of other people, especially in their roles as friends and lovers. For all their subtle sophistication, her narratives are strikingly distinct from those of the ultimate modern Irish writer, James Joyce, to whom her latest novel alludes more than once, whose proffered pleasures can only be won through hard work and study. Rooney’s works contain characters who are in school, but they needn’t be read in school. They are perfectly able to compete in the open market for our leisure time where, as the pages to follow assert, it is the novel’s job, as commodity, to assuage our sense of the limitations of embodied life.

To speak of fiction in the Age of Amazon is perforce to speak of it in relation to the consumer economy, a thing of long duration, a thing of historical stages in its making and only lately arrived at the popular embrace of online commerce. With its origins in the circulation of exotic luxuries in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, increasing spread in the industrializing nineteenth century, and ad-driven explosion in the twentieth, the consumer economy has changed the texture of daily life in countries in which has been able to take root, and continues to do so today, globally. Subsuming, virtualizing, and massively expanding the reach of two remarkable inventions of the mid to late nineteenth century, the department store and mail-order catalog, the company once billing itself “Earth’s Biggest Bookstore” and then the “Everything Store” has helped set the scene for literary life in our time, when any given cardboard box might contain dog treats or sweatpants or tampons or a book; or when the novel as we know it might not even appear in its traditional physical form, downloaded instead from the company’s servers to one or another tributary reading device.

But setting the scene is one thing: has the consumerist ethos embodied in Amazon’s commercial practices been internalized in the novel’s form? The previous two chapters of this book asked a similar question mainly from the side of literary production, tracing the penetration of an entrepreneurial ideal—the author as self-publishing “start-up,” or corporate CEO—in the popular literature of an economy increasingly defined by the conscripted provision of services rather than the industrial production of durable goods. In this and in the following chapter of this book, that perspective will be flipped, allegories of supply giving way to those of demand as we focus on the novel as something, one kind of thing, a person might want to buy, simply, but as it happens not so simply.

“You sound like the ultimate consumer,” says Anastasia Steele upon first meeting the hero of E. L. James’s Fifty Shades of Grey (2011), which with over 125 million copies sold in its first five years in print is a strong candidate for the ultimate best seller. She is interviewing him for the college newspaper, challenging him to explain his desire to possess so many things. Christian’s response to Ana’s charge is simple and remarkably un-defensive: “I am.” That a man who is also introduced as a “mega-industrialist tycoon” who says he “like[s] to build things” and wants to “[feed] the world’s poor” would so easily assent to thinking of himself in this way is interesting, if not exactly shocking. We expect people who make lots of money building things to spend some of that money on other things, on the best things, amazing things. And yet, in a way that will reward further consideration, the consumer-tycoon runs counter to the most prominent image of the capitalist in the history of economic theory, the Protestant “acetic” described by Max Weber in the early twentieth century.

The latter was a figure characterized as much by the restraint of his worldly desires as by his vigorous actions. According to Weber, it was he who, seeing virtue in hard work and seeking profit for profit’s sake, vaulted the Western world into full-blown capitalist modernity, quickly filling the world with new things. The Protestant ethic is expressed most directly, for Weber, in the writings of Ben Franklin, whose maxim “time is money” meant simply to draw the young tradesman’s attention to the hidden costs of his leisure in hours not devoted to productive labor but can sound like an even stronger metaphysical claim about the fabric of the universe. For Franklin, simply to spend money rather than to invest it toward future returns is akin to the profligate spilling of seed, disrupting the reproductive miracle of profit in which, in time, “money can beget money, and its offspring can beget more, and so on” toward ever greater wealth.

Whether or not his conception of the virtuous capitalist had ever adequately explained the rapid transformation of the material environment of human life by modern industry, by the time of Weber’s writing, the Protestant ethic was plainly falling out of sync with Western economies increasingly ideologically centered on mass consumption over and above production for the satisfaction of basic needs—economies in which, indeed, with the advent of modern advertising, forces had recently set about expanding what might count as a basic need. In this world the quasi-spiritual pursuit of profit without end finds itself inverted in the mirror—the maw—of consumer demand, which likewise escalates without apparent end or arrival at enough. Driven by what Émile Zola and others would tendentiously describe as a distinctly feminine instinct for shopping, the economy so constituted would escalate in a virtuous upward spiral of wage-earning and inspired expenditure, with the latter taking the lead.

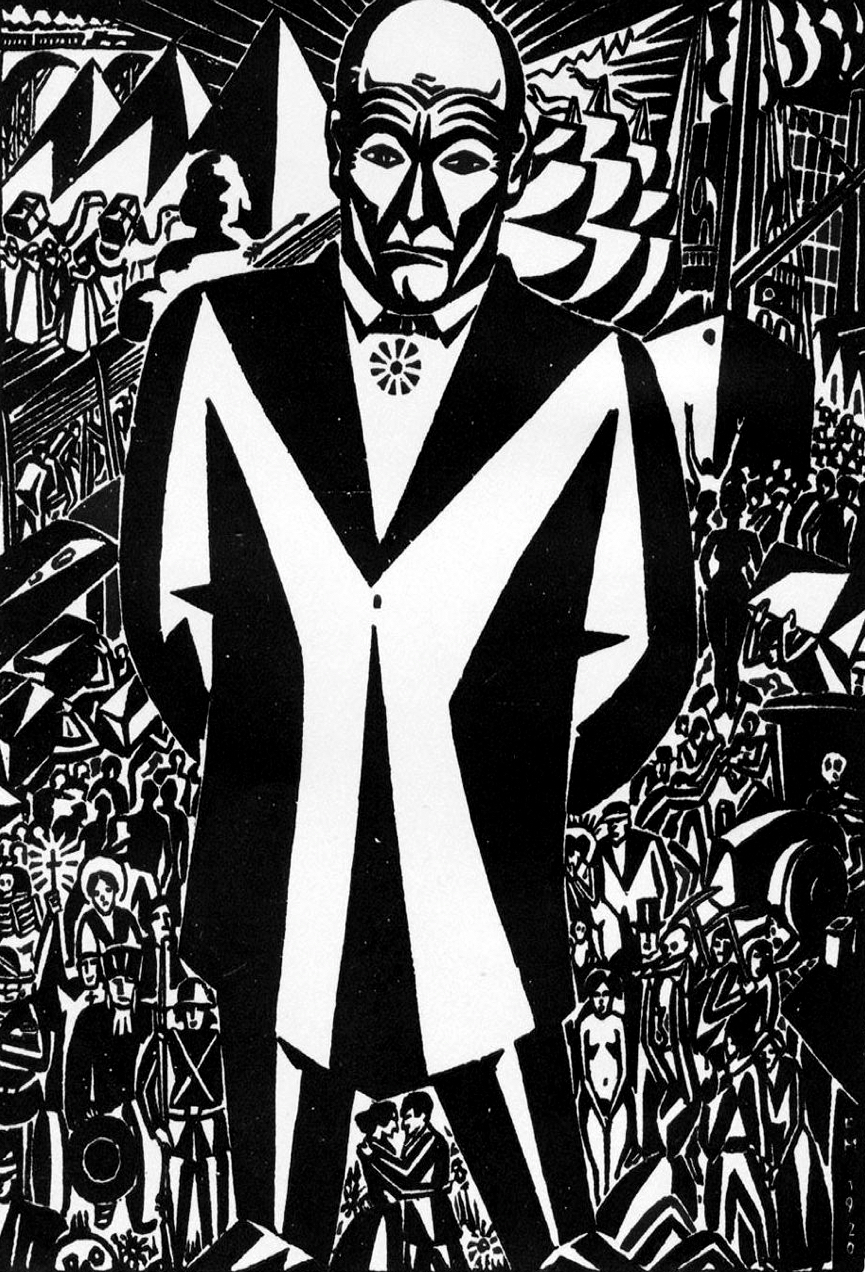

This much we know from any number of accounts of the rise of the modern so-called consumer economy whose latest phase is our own Age of Amazon, where upward of 70 percent of the gross domestic product of a country like the United States is driven by consumer spending, and one of the most closely watched economic indicators is the Index of Consumer Sentiment. What remains is to complicate our understanding of Weber’s capitalist along the same lines—not erasing that figure, exactly, but forcing him to stand next to one of a substantially different nature. That other capitalist is what political journalists and cartoonists of the early twentieth century began to call a “fat cat,” a figure whose very rotundity seems a rebuke to Weber’s version, and to the tagging of the consumer as a woman.

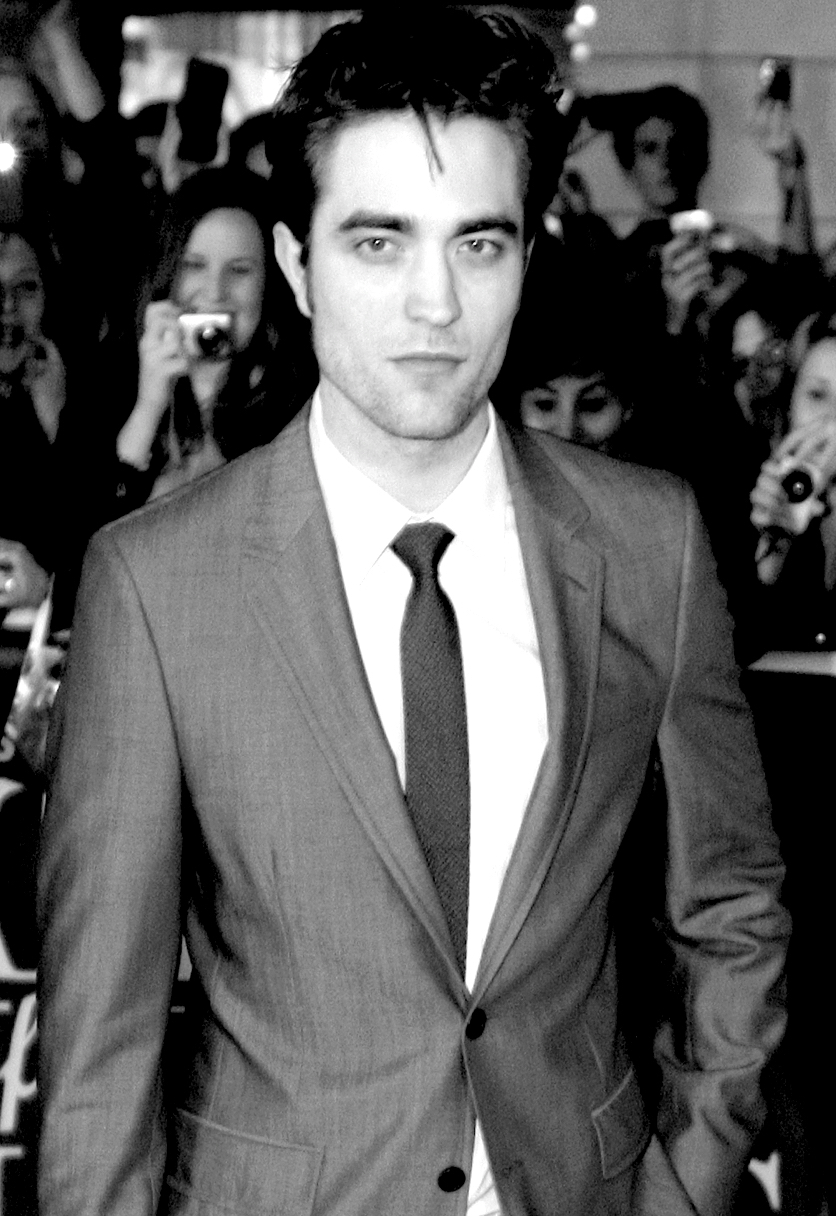

While it has remained convenient to him to be thought of as doing God’s work as a self-sacrificing “job creator,” the capitalist in the mode of fat cat is distinct from ordinary shoppers only in the excessive purchasing power he brings to the check-out counter of life. Having exhausted the possibilities of direct commodity enjoyment, the fat cat indulges in the pleasures of investment itself. When he plays the markets, his work has all the thrill of gambling, but its more productive manifestations are satisfying, too, consuming human and other resources toward the end of amassing personal wealth and worldly power. He is a figure not of self-abnegating asceticism but self-gratifying Eros, not of stern rectitude but selfish excess. At the limit, he is the consumer as predator. Here they stand side by side, but only in their weird superimposition would we begin to see the character of Christian Grey come into focus. Add one more layer, the image of the brooding young movie star/vampire E. L. James had in mind as she was writing the original draft of the novel, and there he is.

He is a man who has seen fit to buy himself a private jet, yacht, helicopter, hang glider, fleet of automobiles, scads of luxury real estate, and a string of submissive lovers, but who manages to project an aura of austerity all the same.

This is visible not least in his lean, pale physical form, but also in the minimalist architectural environments he likes to inhabit (“all curved glass and steel, an architect’s utilitarian fantasy”), in the clean lines of the Apple electronics he and Ana use there, and even in his name. He is, after all, a great champion of discipline, which he assures Ana is the other side of the coin of softer pleasures. We could say he is a bundle of contradictions, but Christian’s way of describing himself is even better. He is, he says, “fifty shades of fucked up,” for reasons it takes Ana some time to learn. Taking his cue, she nicknames him Fifty, and begins to explore his curiously hard-edged plenitude, accompanied in this endeavor by her own psychic multiplicity, an internalized audience of competing “inner goddess” and “subconscious” that corresponds, roughly, to the psychoanalytic id and superego. What follows in the novel and its two successors in the Fifty Shades trilogy are a series of narrative numerical reductions and integrations: from fifty symptoms to the one childhood trauma that explains Christian Grey; from many potential lovers to One True Love; finally, and most importantly for the genre of which Fifty Shades is the best-known member, from indecision in the face of a multiplicity of objects of desire to the assertion of unitary executive will in the solidification of the social form of the couple.

This genre is the contemporary romance novel, specifically a subgenre thereof called “alpha billionaire romance.” Its instances are legion, with titles like Beautiful Bastard, Hardwired, Dirty Billionaire, Loving the White Billionaire, and Bared to You, many of them self-published on Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing system, others appearing as mass-market paperbacks and e-books under well-known imprints, including Amazon’s own Montlake Romance. All but wholly marginal to the con- temporary literary field as seen from the perspective of academic literary studies and adjacent organs of literary journalism, the romance novel is central to popular literary life in the Age of Amazon, where readers are understood as customers, and the customer is queen.

What do we see when we center our view of the literary field on romance rather than on literary fiction? We see the inescapable identity of the novel as a generic commodity, to be sure, but also some of the surprising complexity of its engagement with the realities of consumer culture. While the characters and events of romance are not always “realistic” on the level of representational verisimilitude, they, by their nature, continually reflect upon the economic and otherwise crudely material bases of modern love and life in general, the world not as it might be built anew in some science fiction novel but as it already impinges on everything. In relation to these bases, romance instances what we might call a “functional” or “therapeutic” realism. As we shall see, it is enacted not only in the reader’s encounter with the individual work, but also in the knitting of that encounter into a sequencing of reading experiences, one after the other. The individual work—a trilogy, in this case—is designed to manage a potentially problematic plenitude, sifting a haystack of potential lovers to discover the One, while the genre as a whole, offering readers an endless series of nominally distinct heroes as objects of desire, reinstalls that plenitude as a manageable reading habit whose function is to assuage some of the fundamental existential limitations of embodied life. And yet this complex is already encoded into the singular figure of Christian Grey, the One who is in theory everything a desirable man could be, a would-be epic hero corralled for domestic romantic duty.

Christian’s unusual purchasing power is hardly needed the second time he and Ana meet, when he enters the hardware store where she works to buy some, as it turns out, not-so-innocent masking tape and cable ties. It is very much needed in the next act of purchase he makes in the novel, on his way to acquiring the services of Ana herself as a submissive lover. “Odd. I haven’t ordered anything from Amazon recently,” she thinks when her roommate tells her she has a package. It is not from Amazon but it does contain a book—a fine first edition of Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles, one of the “British classics” Ana has told him that she, a graduating English major, likes to read. The gift is of course multiply self-reflexive. The inscription Christian has borrowed from the novel itself is meant as a playful warning to her about his intentions in giving it, which put her in the position of the novel’s heroine: “Why didn’t you tell me there was danger? Why didn’t you warn me? ... Ladies know what to guard against because they read novels that tell them of these tricks.”Of course, the circumstances of Tess’s ruination are substantially different for Ana, whose virginity at the beginning of this novel is understood even by herself as an anomaly, the genre having modernized itself in various ways even as it has faithfully carried the flame of the marriage plot.

For the reader of the novel, meanwhile, the gift points to the book she (that is in all likelihood the reader’s gender) holds in hand, which, if it is the best-known example of the alpha billionaire romance, is also in lineage with the English novel stretching back through Hardy and Henry James to Jane Austen and Samuel Richardson. Richardson’s 1740 best seller, Pamela: Or, Virtue Rewarded, was the first major work to serve what would prove an endless demand in the modern book market for the story of a young woman’s triumph in bringing an abusive male to heel as a husband. At the same time, and relatedly, it announced that female readers would be crucial to the market for novels in general, much more so than men.

Grey’s gift is at once the expression and negation of the Amazon economy explicitly referenced in this moment— pointing, in its high cost, to the nature of the book as a purchasable commodity even as that high cost is precisely what Amazon would diminish in its facilitation of popular literary commerce, where, as infamously asserted by Jeff Bezos, new books should be downloadable for $9.99 at most. The stealthy e-book format reputedly so important to the novel’s success as “mommy porn” is something like the opposite of the fine first edition. It converts the novel’s obtrusive materiality into evanescent bits drifting profitably from device to device. This truth is brought home when, in the second volume of the Fifty Shades trilogy, Fifty Shades Darker, Ana is given an Apple iPad tablet supplied with a fictional British Library App, providing her electronic access to all the classic novels she could possibly find time to read. “I exit quickly, knowing I could be lost in this app for an eternity,” she says, hitting upon one of the key features of literary life in the Age of Amazon, where a hyper-abundance of inexpensive product collides with a general scarcity of time for its consumption.

It is, however, in the last layer of the trilogy’s self-reflexivity that we see the deepest and most interesting fusion of the romance with the realities of consumer culture. It is reflexivity to the second degree, reflecting as it does a long history of reflexivity itself in the genre, whose heroines are frequently enough represented as readers. Think here of Jane Austen’s Elizabeth Bennett, who “is a great reader and has no pleasure in anything else,” or of the many female heirs—Emma Bovary, preeminently —to the original reader of romances in the history of the novel, Don Quixote. If we have been taught to think of these reflexive incorporations of the reader as demystifying romance on behalf of hard-nosed novelistic realism, the persistence of the same phenomenon in works to all appearances wholly committed to the romantic fantasy suggests it is of somewhat larger significance, with reinforcing as well as critical tendencies.

Most fundamentally, it is a symptom of the modern “codification of intimacy,” as Niklas Luhmann calls it. For Luhmann, this term gets at how, beginning in the seventeenth century, what had generally been thought the essential madness of romantic love was made functional in the routine task of social reproduction. In his account, faced with an increasingly differentiated and contingent modern social reality, chivalric forms heretofore centered on aristocratic extramarital relations (think Lancelot and Guinevere) were updated for use in the imaginative construction of reassuringly small and mutually self-confirming bourgeois worlds. Consuming the romance, that is, readers were systematically instructed in the pursuit of the intensive pseudo- totality of the marriage bond newly conceived as a source of deep emotional satisfaction to individuals rather than as an alliance between families. Structured as a quest for the One True Love as marriage partner, it was and remains an ironically generic pursuit, driven by an “emotion preformed, and indeed prescribed, in literature, and no longer directed by social institutions such as the family and religion.” For Luhmann, modern love “seems to come from nowhere, arises with the aid of copied patterns, copied emotions, copied existences and may perhaps create a conscious awareness of this secondhand character in its failure.” It makes sense that the engine of these secondhand emotions, reading, would on occasion see its own reflection, as it were, in print.

It only needs to be added that both these conceptions can be reinscribed in and as a function of the history of consumer capitalism. What Luhmann describes as the literary autonomization of love in early modernity could be viewed instead as the gradual transfer of authority over amatory relations to a market, what is known as the “marriage market”—a locution that took off in the late nineteenth century—in which bride and groom would each be reciprocally conceived as buyer and seller, consumer and consumed. The irony of this transfer for Luhmann’s cocoon-like “pseudo-totality” is that it places unprecedented stress on the marriage bond, leading ultimately to high instances of divorce, including “no-fault divorce,” the relationship equivalent of the free return. While it would not often call for the purchase of first editions of classic literature, the ritual of courtship that ended in marriage, once conducted in the private parlor, would henceforth take the form of “dating,” which was indeed an occasion for significant financial outlay in highly codified, mimetically inspired channels. As Daniel Harris explains, “Before the twentieth century, there were no dates, no lavish nights on the town in which men shelled out an entire month’s wages for corsages, highballs at Delmonico’s, five-course meals at the 21 Club, tickets for Broadway plays ...” There was no “love industry” and attendant genre of advertising, whose repetitive forms assume that “love is such a universal experience that it reduces us all to the same generic person, the same beach-walker, the same sunset-admirer, who relies on the same commercially manufactured images of intimacy.”

This is true as far as it goes, establishing an important context for the modern romance novel, but arguably betrays too much confidence that modern lovers have ever been other than generic in their loving, let alone their lovemaking. Already in the seventeenth century, long before anyone thought of going on a date to Delmonico’s, François de La Rochefoucauld could deliver a maxim, “People would never fall in love if they hadn’t heard love talked about,” predicated on the reflexive unoriginality of that emotion; and it may be the case, then as now and at every moment in between, that the cognitive mechanism of idealization so crucial to love makes it an inevitably generic phenomenon.

People speak unembarrassedly of being attracted to one or another romantic “type,” and can be observed behaviorally to define their objects of desire in terms assimilable to the acronymic code made famous in personal ads of the newsprint era, beginning with the still-regnant binary M or F—a code whose main use, now that the function of personals has largely been absorbed into more complexly algorithmic internet dating sites, is to label different types either of pornography or romance novel. An example would be the thriving genre of “BBW Romance,” which features big, beautiful women and the typically burly men who love them. What’s remarkable about the romance is how deep its knowledge of the essentially generic nature of desire goes even as it keeps faith, superficially, with the fantasy of One True Love.

Neither, relatedly, is Harris’s formulation responsive to the paradoxical generic singularity of the alpha billionaire as a remarkable man. His godlike excellence would seem at least partly to refute the idea that we are “all the same,” no? In the real world this figure is so often a repulsive grotesque; here in Amazonia he is a sleek server of emotional needs. He is the desiring man, the subject of desire, conceived and constructed as an object of desire, and suffused in that reverberating fantasy circuit with unpredictably utopian as well as reactionary ideological spirits. The romance novel is in this sense a set of imaginary negotiations with the realities of patriarchal capitalism, part of the long tradition in the novel drawn to our attention by Nancy Armstrong in Desire and Domestic Fiction (1987).

At this late date, unless I am mistaken, the optimism of that earlier political moment in the history of the novel has been blunted, and the discourse has become more ameliorative in its aims, more a therapeutic coping mechanism than the echo or instigator of a positive program. I don’t know that anyone has improved upon the incisive formulation of the essential political conundrum of the genre offered in Janice Radway’s classic work of cultural anthropology, Reading the Romance (1984):

I would only add that, responsive to the desires of its readers, the romance hero is not necessarily to be confused with his real-world counterpart. To want the literary alpha billionaire is to want him to want you, yes, but it is also to want to set the terms of his desire, to get inside it and take the wheel.

As though it is not enough to leave this implicit, the state of the art in the genre, which by and large favors first-person narratives from the heroine’s point of view, is to find ways of inhabiting his consciousness, too. And so, in works like Pamela Aidan’s An Assembly Such as This (2006) or Janet Aylmer’s Darcy’s Story (2007), Austen’s romance is retold from the hero’s perspective. In Christina Lauren’s self-published modern romance sensation, Beautiful Bastard, chapters alternate between the heroine’s perspective and that of her boss, whose brutal sexual harassment of her in the workplace looks like something else from his (and eventually her) point of view: it looks like falling helplessly in love. (Perhaps ominously, in this novel the modern context of workplace sexual harassment policies has been folded into the romance, lending their lovemaking a further charge of forbidden-ness.) For her part, when she completed the Fifty Shades trilogy, E. L. James set about rewriting the whole thing from Christian’s perspective, beginning with the novel called simply Grey (2015). As Cora Kaplan noted some time ago, against our habit of thinking about the mechanics of identification as a straight line between reader and character, especially a protagonist, it may instead be identification with a character system, a structure. It might also be a mistake to think that that structure is indistinguishable from the non-textual ones upon which it is based.

For all that his wealth and power hold him above the humiliations of ordinary servile life, the alpha billionaire is after all “unmanned,” drawn by force of his own attraction to the heroine into the role of protector, traditionally enough, but also caregiver and even, dare we say, nurturer. One of the repeated motifs of Fifty Shades of Grey and its sequels is Christian’s constant, nagging insistence to Ana that she should eat more: “‘Eat,’ he says more sharply. ‘Anastasia, I have an issue with wasted food ... eat.’” His obsessive concern for consumption in its original sense stems, we eventually learn, from his having grown up hungry, the child of a neglectful “crack whore” and victim of horrific abuse by her pimp. Fifty Shades of Grey is in other words a trauma narrative. It asks us to see the pitiful underdog hiding inside the master of the universe, the hungry boy inside the ultimate consumer, with nary a sympathetic thought for the plight of that namelessly bad mother, known only by her epithet, who might have had her own story to tell. Imagining what that story might have been, we come to suspect that the “real” trauma at the heart of the novel, and perhaps of the alpha billionaire genre as a whole, is the existential threat of patriarchal capitalist violence, from the symbolic violence of demeaning and dehumanizing contempt to the physical violence of abuse, rape, and murder. The secondary trauma would be the discovery that your mother cannot finally protect you from that threat, inasmuch as she has been and remains subject to the same dangers, or worse, and has had to make her own accommodations.

In this context, the context of Christian as victim, the sexual pleasure he takes in hurting women who look like his mother is meant to seem understandable, if not as laudable as his desire to feed the world’s poor. It is not a fundamental character flaw but a condition Ana can help him to heal, leading the way to the homely joys of what they together call “vanilla” sex. At the same time, such is the mobility of this allegorical figure that the fearful little boy is also a kind of stand-in mother to Ana, whose own mother is presented in the novel as a flighty and unreliable multiple divorcée. Christian’s gradual willingness to supply emotional labor to Ana is no small part of the commodity being consumed, in a kind of return to the primal scene of literary comfort, the cozy bedtime story. Thus, while it is tempting to read him as little more than a poster boy for neoliberal capitalism, for that set of brutalities, he is also the symbolic vehicle by which that system is “softened” and made caring again in the little welfare state of a loving marriage.

Even so, there is surely a limit to the crypto-feminization of the alpha billionaire, a limit to the perhaps surprisingly polymorphous flexibility of his gender, which is in fact continually in the way of being made one in the smithy of pure masculine will. While Christian can seem surprisingly motherly at times, his main utility as an “alpha” is to offer symbolic resistance to the general “feminization” of life in a consumer economy, where all roads lead back to the docile bodies of the domestic sphere, and where emotional labor—the provision of good service—is the order of the day for workers of all genders. Consumerism constructs the world in expectation of a general receptivity on the part of shoppers and workers alike, rather than as the heroic extrusion of supply. The alpha billionaire responds to that feminization by asserting the authority of the unitary executive. As Christian tells Ana, “I own my company. I don’t have to answer to a board,” and from Pride and Prejudice to the present, independent wealth appears as a feature of the romance hero again and again.

If it weren’t so obvious, it would be quite astounding how faithful to this kind of man the genre is, how many modes of dependent masculinity it excludes from the hero slot. The psychic utility of the so-called authoritarian personality to those around him has been analyzed by Erich Fromm, Theodor Adorno, and others, and has been linked to a deep uneasiness on the part of the modern masses with the novelty of their own freedom. To an extent more extreme than the world-unto- itself of marriage described by Luhmann, to “marry” the alpha leader in a psychological sense is to be absolved of the existential inconvenience of choice. Selling Ana on the idea of her own submission, Christian makes this perfectly explicit: “All those decisions—all the wearying thought processes behind them. The ‘is this the right thing to do? Should this happen here? Can it happen now?’ You wouldn’t have to worry about any of that detail. That’s what I’d do as your Dom.” Will she buy? Her decision is akin to that of the citizen of a democracy who contemplates voting in a dictatorship.

The particular existential dilemma of “freedom of choice” most relevant to the romance novel is, however, a discernably distinct if adjacent one. It occurs not at the ballot box but at the intersection of human intimacy and consumer capitalism. It springs from the essential seriality of the latter’s efforts to provide ever-novel forms of customer satisfaction, the drive toward which might at any point supersede loyalty to a given product. This is where the alpha’s preternatural decisive-ness comes in: “‘You. Are. Mine,’ he snarls, emphasizing each word.” So complete is his certainty that you are for him, and he for you, you can be sure he will stay with you forever. He will be your knight in shining armor tilting against time, warding off the arrival of new objects of his desire and yours.

In this sense, even as he admits to being the ultimate consumer, the alpha billionaire presents himself as a fantasy antidote to consumerism. That he—or a man much like him—does so for the habitual romance reader in novel after novel, again and again, is what gives away the game: the deepest problem, it turns out, is not that there are too many potential objects of desire, but that you have but one life to live, as they say, for pursuing them. And this, as we shall see, is where the romance genre’s fundamental, as it were, indecisiveness comes in, its freedom from determination: set free, as a series of repeatable fictions, from the terminal linearity of real time, the novel offers itself as an ongoing, pleasurable existential supplement to inherently limited lives.

What will be surprising, perhaps, to anyone who thinks the alpha billionaire romance is uniquely incoherent or cynical in being founded on these paradoxes, is how central they have been to the historical unfolding of the novel form as such, which has only sometimes appeared in the form we call the realist novel but has always been deeply conditioned by the dictates of the real world.

This is visible not least in his lean, pale physical form, but also in the minimalist architectural environments he likes to inhabit (“all curved glass and steel, an architect’s utilitarian fantasy”), in the clean lines of the Apple electronics he and Ana use there, and even in his name. He is, after all, a great champion of discipline, which he assures Ana is the other side of the coin of softer pleasures. We could say he is a bundle of contradictions, but Christian’s way of describing himself is even better. He is, he says, “fifty shades of fucked up,” for reasons it takes Ana some time to learn. Taking his cue, she nicknames him Fifty, and begins to explore his curiously hard-edged plenitude, accompanied in this endeavor by her own psychic multiplicity, an internalized audience of competing “inner goddess” and “subconscious” that corresponds, roughly, to the psychoanalytic id and superego. What follows in the novel and its two successors in the Fifty Shades trilogy are a series of narrative numerical reductions and integrations: from fifty symptoms to the one childhood trauma that explains Christian Grey; from many potential lovers to One True Love; finally, and most importantly for the genre of which Fifty Shades is the best-known member, from indecision in the face of a multiplicity of objects of desire to the assertion of unitary executive will in the solidification of the social form of the couple.

This genre is the contemporary romance novel, specifically a subgenre thereof called “alpha billionaire romance.” Its instances are legion, with titles like Beautiful Bastard, Hardwired, Dirty Billionaire, Loving the White Billionaire, and Bared to You, many of them self-published on Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing system, others appearing as mass-market paperbacks and e-books under well-known imprints, including Amazon’s own Montlake Romance. All but wholly marginal to the con- temporary literary field as seen from the perspective of academic literary studies and adjacent organs of literary journalism, the romance novel is central to popular literary life in the Age of Amazon, where readers are understood as customers, and the customer is queen.

What do we see when we center our view of the literary field on romance rather than on literary fiction? We see the inescapable identity of the novel as a generic commodity, to be sure, but also some of the surprising complexity of its engagement with the realities of consumer culture. While the characters and events of romance are not always “realistic” on the level of representational verisimilitude, they, by their nature, continually reflect upon the economic and otherwise crudely material bases of modern love and life in general, the world not as it might be built anew in some science fiction novel but as it already impinges on everything. In relation to these bases, romance instances what we might call a “functional” or “therapeutic” realism. As we shall see, it is enacted not only in the reader’s encounter with the individual work, but also in the knitting of that encounter into a sequencing of reading experiences, one after the other. The individual work—a trilogy, in this case—is designed to manage a potentially problematic plenitude, sifting a haystack of potential lovers to discover the One, while the genre as a whole, offering readers an endless series of nominally distinct heroes as objects of desire, reinstalls that plenitude as a manageable reading habit whose function is to assuage some of the fundamental existential limitations of embodied life. And yet this complex is already encoded into the singular figure of Christian Grey, the One who is in theory everything a desirable man could be, a would-be epic hero corralled for domestic romantic duty.

Christian’s unusual purchasing power is hardly needed the second time he and Ana meet, when he enters the hardware store where she works to buy some, as it turns out, not-so-innocent masking tape and cable ties. It is very much needed in the next act of purchase he makes in the novel, on his way to acquiring the services of Ana herself as a submissive lover. “Odd. I haven’t ordered anything from Amazon recently,” she thinks when her roommate tells her she has a package. It is not from Amazon but it does contain a book—a fine first edition of Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles, one of the “British classics” Ana has told him that she, a graduating English major, likes to read. The gift is of course multiply self-reflexive. The inscription Christian has borrowed from the novel itself is meant as a playful warning to her about his intentions in giving it, which put her in the position of the novel’s heroine: “Why didn’t you tell me there was danger? Why didn’t you warn me? ... Ladies know what to guard against because they read novels that tell them of these tricks.”Of course, the circumstances of Tess’s ruination are substantially different for Ana, whose virginity at the beginning of this novel is understood even by herself as an anomaly, the genre having modernized itself in various ways even as it has faithfully carried the flame of the marriage plot.

For the reader of the novel, meanwhile, the gift points to the book she (that is in all likelihood the reader’s gender) holds in hand, which, if it is the best-known example of the alpha billionaire romance, is also in lineage with the English novel stretching back through Hardy and Henry James to Jane Austen and Samuel Richardson. Richardson’s 1740 best seller, Pamela: Or, Virtue Rewarded, was the first major work to serve what would prove an endless demand in the modern book market for the story of a young woman’s triumph in bringing an abusive male to heel as a husband. At the same time, and relatedly, it announced that female readers would be crucial to the market for novels in general, much more so than men.

Grey’s gift is at once the expression and negation of the Amazon economy explicitly referenced in this moment— pointing, in its high cost, to the nature of the book as a purchasable commodity even as that high cost is precisely what Amazon would diminish in its facilitation of popular literary commerce, where, as infamously asserted by Jeff Bezos, new books should be downloadable for $9.99 at most. The stealthy e-book format reputedly so important to the novel’s success as “mommy porn” is something like the opposite of the fine first edition. It converts the novel’s obtrusive materiality into evanescent bits drifting profitably from device to device. This truth is brought home when, in the second volume of the Fifty Shades trilogy, Fifty Shades Darker, Ana is given an Apple iPad tablet supplied with a fictional British Library App, providing her electronic access to all the classic novels she could possibly find time to read. “I exit quickly, knowing I could be lost in this app for an eternity,” she says, hitting upon one of the key features of literary life in the Age of Amazon, where a hyper-abundance of inexpensive product collides with a general scarcity of time for its consumption.

It is, however, in the last layer of the trilogy’s self-reflexivity that we see the deepest and most interesting fusion of the romance with the realities of consumer culture. It is reflexivity to the second degree, reflecting as it does a long history of reflexivity itself in the genre, whose heroines are frequently enough represented as readers. Think here of Jane Austen’s Elizabeth Bennett, who “is a great reader and has no pleasure in anything else,” or of the many female heirs—Emma Bovary, preeminently —to the original reader of romances in the history of the novel, Don Quixote. If we have been taught to think of these reflexive incorporations of the reader as demystifying romance on behalf of hard-nosed novelistic realism, the persistence of the same phenomenon in works to all appearances wholly committed to the romantic fantasy suggests it is of somewhat larger significance, with reinforcing as well as critical tendencies.

Most fundamentally, it is a symptom of the modern “codification of intimacy,” as Niklas Luhmann calls it. For Luhmann, this term gets at how, beginning in the seventeenth century, what had generally been thought the essential madness of romantic love was made functional in the routine task of social reproduction. In his account, faced with an increasingly differentiated and contingent modern social reality, chivalric forms heretofore centered on aristocratic extramarital relations (think Lancelot and Guinevere) were updated for use in the imaginative construction of reassuringly small and mutually self-confirming bourgeois worlds. Consuming the romance, that is, readers were systematically instructed in the pursuit of the intensive pseudo- totality of the marriage bond newly conceived as a source of deep emotional satisfaction to individuals rather than as an alliance between families. Structured as a quest for the One True Love as marriage partner, it was and remains an ironically generic pursuit, driven by an “emotion preformed, and indeed prescribed, in literature, and no longer directed by social institutions such as the family and religion.” For Luhmann, modern love “seems to come from nowhere, arises with the aid of copied patterns, copied emotions, copied existences and may perhaps create a conscious awareness of this secondhand character in its failure.” It makes sense that the engine of these secondhand emotions, reading, would on occasion see its own reflection, as it were, in print.

It only needs to be added that both these conceptions can be reinscribed in and as a function of the history of consumer capitalism. What Luhmann describes as the literary autonomization of love in early modernity could be viewed instead as the gradual transfer of authority over amatory relations to a market, what is known as the “marriage market”—a locution that took off in the late nineteenth century—in which bride and groom would each be reciprocally conceived as buyer and seller, consumer and consumed. The irony of this transfer for Luhmann’s cocoon-like “pseudo-totality” is that it places unprecedented stress on the marriage bond, leading ultimately to high instances of divorce, including “no-fault divorce,” the relationship equivalent of the free return. While it would not often call for the purchase of first editions of classic literature, the ritual of courtship that ended in marriage, once conducted in the private parlor, would henceforth take the form of “dating,” which was indeed an occasion for significant financial outlay in highly codified, mimetically inspired channels. As Daniel Harris explains, “Before the twentieth century, there were no dates, no lavish nights on the town in which men shelled out an entire month’s wages for corsages, highballs at Delmonico’s, five-course meals at the 21 Club, tickets for Broadway plays ...” There was no “love industry” and attendant genre of advertising, whose repetitive forms assume that “love is such a universal experience that it reduces us all to the same generic person, the same beach-walker, the same sunset-admirer, who relies on the same commercially manufactured images of intimacy.”

This is true as far as it goes, establishing an important context for the modern romance novel, but arguably betrays too much confidence that modern lovers have ever been other than generic in their loving, let alone their lovemaking. Already in the seventeenth century, long before anyone thought of going on a date to Delmonico’s, François de La Rochefoucauld could deliver a maxim, “People would never fall in love if they hadn’t heard love talked about,” predicated on the reflexive unoriginality of that emotion; and it may be the case, then as now and at every moment in between, that the cognitive mechanism of idealization so crucial to love makes it an inevitably generic phenomenon.

People speak unembarrassedly of being attracted to one or another romantic “type,” and can be observed behaviorally to define their objects of desire in terms assimilable to the acronymic code made famous in personal ads of the newsprint era, beginning with the still-regnant binary M or F—a code whose main use, now that the function of personals has largely been absorbed into more complexly algorithmic internet dating sites, is to label different types either of pornography or romance novel. An example would be the thriving genre of “BBW Romance,” which features big, beautiful women and the typically burly men who love them. What’s remarkable about the romance is how deep its knowledge of the essentially generic nature of desire goes even as it keeps faith, superficially, with the fantasy of One True Love.

Neither, relatedly, is Harris’s formulation responsive to the paradoxical generic singularity of the alpha billionaire as a remarkable man. His godlike excellence would seem at least partly to refute the idea that we are “all the same,” no? In the real world this figure is so often a repulsive grotesque; here in Amazonia he is a sleek server of emotional needs. He is the desiring man, the subject of desire, conceived and constructed as an object of desire, and suffused in that reverberating fantasy circuit with unpredictably utopian as well as reactionary ideological spirits. The romance novel is in this sense a set of imaginary negotiations with the realities of patriarchal capitalism, part of the long tradition in the novel drawn to our attention by Nancy Armstrong in Desire and Domestic Fiction (1987).

At this late date, unless I am mistaken, the optimism of that earlier political moment in the history of the novel has been blunted, and the discourse has become more ameliorative in its aims, more a therapeutic coping mechanism than the echo or instigator of a positive program. I don’t know that anyone has improved upon the incisive formulation of the essential political conundrum of the genre offered in Janice Radway’s classic work of cultural anthropology, Reading the Romance (1984):

Does the romance’s endless rediscovery of the virtues of a passive female sexuality merely stitch the reader ever more resolutely into the fabric of patriarchal culture? Or, alternatively, does the satisfaction a reader derives from the act of reading itself, an act she chooses, often in explicit defiance of others’ opposition, lead to a new sense of strength and independence?

I would only add that, responsive to the desires of its readers, the romance hero is not necessarily to be confused with his real-world counterpart. To want the literary alpha billionaire is to want him to want you, yes, but it is also to want to set the terms of his desire, to get inside it and take the wheel.

As though it is not enough to leave this implicit, the state of the art in the genre, which by and large favors first-person narratives from the heroine’s point of view, is to find ways of inhabiting his consciousness, too. And so, in works like Pamela Aidan’s An Assembly Such as This (2006) or Janet Aylmer’s Darcy’s Story (2007), Austen’s romance is retold from the hero’s perspective. In Christina Lauren’s self-published modern romance sensation, Beautiful Bastard, chapters alternate between the heroine’s perspective and that of her boss, whose brutal sexual harassment of her in the workplace looks like something else from his (and eventually her) point of view: it looks like falling helplessly in love. (Perhaps ominously, in this novel the modern context of workplace sexual harassment policies has been folded into the romance, lending their lovemaking a further charge of forbidden-ness.) For her part, when she completed the Fifty Shades trilogy, E. L. James set about rewriting the whole thing from Christian’s perspective, beginning with the novel called simply Grey (2015). As Cora Kaplan noted some time ago, against our habit of thinking about the mechanics of identification as a straight line between reader and character, especially a protagonist, it may instead be identification with a character system, a structure. It might also be a mistake to think that that structure is indistinguishable from the non-textual ones upon which it is based.

For all that his wealth and power hold him above the humiliations of ordinary servile life, the alpha billionaire is after all “unmanned,” drawn by force of his own attraction to the heroine into the role of protector, traditionally enough, but also caregiver and even, dare we say, nurturer. One of the repeated motifs of Fifty Shades of Grey and its sequels is Christian’s constant, nagging insistence to Ana that she should eat more: “‘Eat,’ he says more sharply. ‘Anastasia, I have an issue with wasted food ... eat.’” His obsessive concern for consumption in its original sense stems, we eventually learn, from his having grown up hungry, the child of a neglectful “crack whore” and victim of horrific abuse by her pimp. Fifty Shades of Grey is in other words a trauma narrative. It asks us to see the pitiful underdog hiding inside the master of the universe, the hungry boy inside the ultimate consumer, with nary a sympathetic thought for the plight of that namelessly bad mother, known only by her epithet, who might have had her own story to tell. Imagining what that story might have been, we come to suspect that the “real” trauma at the heart of the novel, and perhaps of the alpha billionaire genre as a whole, is the existential threat of patriarchal capitalist violence, from the symbolic violence of demeaning and dehumanizing contempt to the physical violence of abuse, rape, and murder. The secondary trauma would be the discovery that your mother cannot finally protect you from that threat, inasmuch as she has been and remains subject to the same dangers, or worse, and has had to make her own accommodations.

In this context, the context of Christian as victim, the sexual pleasure he takes in hurting women who look like his mother is meant to seem understandable, if not as laudable as his desire to feed the world’s poor. It is not a fundamental character flaw but a condition Ana can help him to heal, leading the way to the homely joys of what they together call “vanilla” sex. At the same time, such is the mobility of this allegorical figure that the fearful little boy is also a kind of stand-in mother to Ana, whose own mother is presented in the novel as a flighty and unreliable multiple divorcée. Christian’s gradual willingness to supply emotional labor to Ana is no small part of the commodity being consumed, in a kind of return to the primal scene of literary comfort, the cozy bedtime story. Thus, while it is tempting to read him as little more than a poster boy for neoliberal capitalism, for that set of brutalities, he is also the symbolic vehicle by which that system is “softened” and made caring again in the little welfare state of a loving marriage.

Even so, there is surely a limit to the crypto-feminization of the alpha billionaire, a limit to the perhaps surprisingly polymorphous flexibility of his gender, which is in fact continually in the way of being made one in the smithy of pure masculine will. While Christian can seem surprisingly motherly at times, his main utility as an “alpha” is to offer symbolic resistance to the general “feminization” of life in a consumer economy, where all roads lead back to the docile bodies of the domestic sphere, and where emotional labor—the provision of good service—is the order of the day for workers of all genders. Consumerism constructs the world in expectation of a general receptivity on the part of shoppers and workers alike, rather than as the heroic extrusion of supply. The alpha billionaire responds to that feminization by asserting the authority of the unitary executive. As Christian tells Ana, “I own my company. I don’t have to answer to a board,” and from Pride and Prejudice to the present, independent wealth appears as a feature of the romance hero again and again.

If it weren’t so obvious, it would be quite astounding how faithful to this kind of man the genre is, how many modes of dependent masculinity it excludes from the hero slot. The psychic utility of the so-called authoritarian personality to those around him has been analyzed by Erich Fromm, Theodor Adorno, and others, and has been linked to a deep uneasiness on the part of the modern masses with the novelty of their own freedom. To an extent more extreme than the world-unto- itself of marriage described by Luhmann, to “marry” the alpha leader in a psychological sense is to be absolved of the existential inconvenience of choice. Selling Ana on the idea of her own submission, Christian makes this perfectly explicit: “All those decisions—all the wearying thought processes behind them. The ‘is this the right thing to do? Should this happen here? Can it happen now?’ You wouldn’t have to worry about any of that detail. That’s what I’d do as your Dom.” Will she buy? Her decision is akin to that of the citizen of a democracy who contemplates voting in a dictatorship.

The particular existential dilemma of “freedom of choice” most relevant to the romance novel is, however, a discernably distinct if adjacent one. It occurs not at the ballot box but at the intersection of human intimacy and consumer capitalism. It springs from the essential seriality of the latter’s efforts to provide ever-novel forms of customer satisfaction, the drive toward which might at any point supersede loyalty to a given product. This is where the alpha’s preternatural decisive-ness comes in: “‘You. Are. Mine,’ he snarls, emphasizing each word.” So complete is his certainty that you are for him, and he for you, you can be sure he will stay with you forever. He will be your knight in shining armor tilting against time, warding off the arrival of new objects of his desire and yours.

In this sense, even as he admits to being the ultimate consumer, the alpha billionaire presents himself as a fantasy antidote to consumerism. That he—or a man much like him—does so for the habitual romance reader in novel after novel, again and again, is what gives away the game: the deepest problem, it turns out, is not that there are too many potential objects of desire, but that you have but one life to live, as they say, for pursuing them. And this, as we shall see, is where the romance genre’s fundamental, as it were, indecisiveness comes in, its freedom from determination: set free, as a series of repeatable fictions, from the terminal linearity of real time, the novel offers itself as an ongoing, pleasurable existential supplement to inherently limited lives.

What will be surprising, perhaps, to anyone who thinks the alpha billionaire romance is uniquely incoherent or cynical in being founded on these paradoxes, is how central they have been to the historical unfolding of the novel form as such, which has only sometimes appeared in the form we call the realist novel but has always been deeply conditioned by the dictates of the real world.

Mark McGURL is the Albert Guérard Professor of Literature at Stanford University. His last book, THE PROGRAM ERA, won the Truman Capote Award for Literary Criticism, 2011. McGURL has previously worked for The New York Times and The New York Review of Books.

Order a copy of EVERYTHING & LESS

direct from the publisher here.

Order a copy of EVERYTHING & LESS

direct from the publisher here.