LET IT

PERCOLATE—

A MANIFESTO

FOR READING

Sophie SEITA

First presented at BROWN UNIVERSITY

(Translation Across Disciplines, 28 February 2020);

& again at HARVARD UNIVERSITY

(Contemporary Translation in Transition, 6 March 2020);

& then transcribed and published in

BRICKS FROM THE KILN #4...

(see here)

‘To translate is to surpass the source’—these are some words I put into the mouth of a character in My Little Enlightenment Plays, a performance project in which I rewrote, translated, responded to and, one could say, corresponded with some Enlightenment thinkers and writers.

Words can contextualise, embellish, explain. They can be raw, they can be tender, they can be violent. They can be matter of fact or they can translate matter into something else. Words force us to be nuanced.

While translation trades in words, it also encompasses, for me, the moving of material from one place to another. Which is admittedly a broad delineation. But capaciousness can be a generosity. So. Translation might mean moving a language, an idea, an image, a material (like paper or clay) to a known or unknown elsewhere, or it might mean transforming it into another form or context.

This piece, which is a kind of delirious reading in progress, will propose a sprawling and lounging understanding of translation:

Using Sara Ahmed’s terminology in her manifesto Living a Feminist Life, translation is in my ‘feminist killjoy survival kit.’1

Which is another thing I put into a play. When I translate, I keep everything in play. Or at bay? Sound play, like any good tutor, imparts knowledge by osmosis.

Translation is a deeply pedagogical form. Because it teaches you to read. So here’s my manifesto for reading.

These almost-wise and not-quite-adamant demands serve a pragmatic truth. Which is provisional. And admits to not-knowing.

‘Not knowing,’ as Jack Halberstam suggests in The Queer Art of Failure, may in fact offer more creative, more cooperative [and] surprising ways of being in the world.’3 Translation, like a manifesto, like pedagogy, is of a delayed futurity. If this were a proper manifesto, or a classroom, I would invoke a “we,” a call for action.

What action is reading?

Taking a shower is an activity. Taking a bath professes not-doing. To write in the bath is to enter the jurisdiction of floating. Of idleness. Lisa Robertson’s she-dandy allows herself to pursue her thoughts languorously. What knowledge does leisure afford?

Working on a translation you do figure eights of reading. ‘To rush it breathlessly through does very well for a beginning. But that is not the way to read finally.’4 Virginia Woolf is speaking about the need to re-read a novel here, but her comment also resonates with our critical desire to extract, to unearth, as a means to an end.

Is parsing always in cahoots with parsimony? Avoid finality! Etc. A non-extractive reading might be one that answers in kind: not by translation into a different discourse, but by using a creative circuitry of aesthetic kinship. Writing-through-reading can mean taking it in, chewing it. Letting it percolate.

In my teaching, I promote what I call ‘translational reading,’ which tries to understand a text by doing something with it.

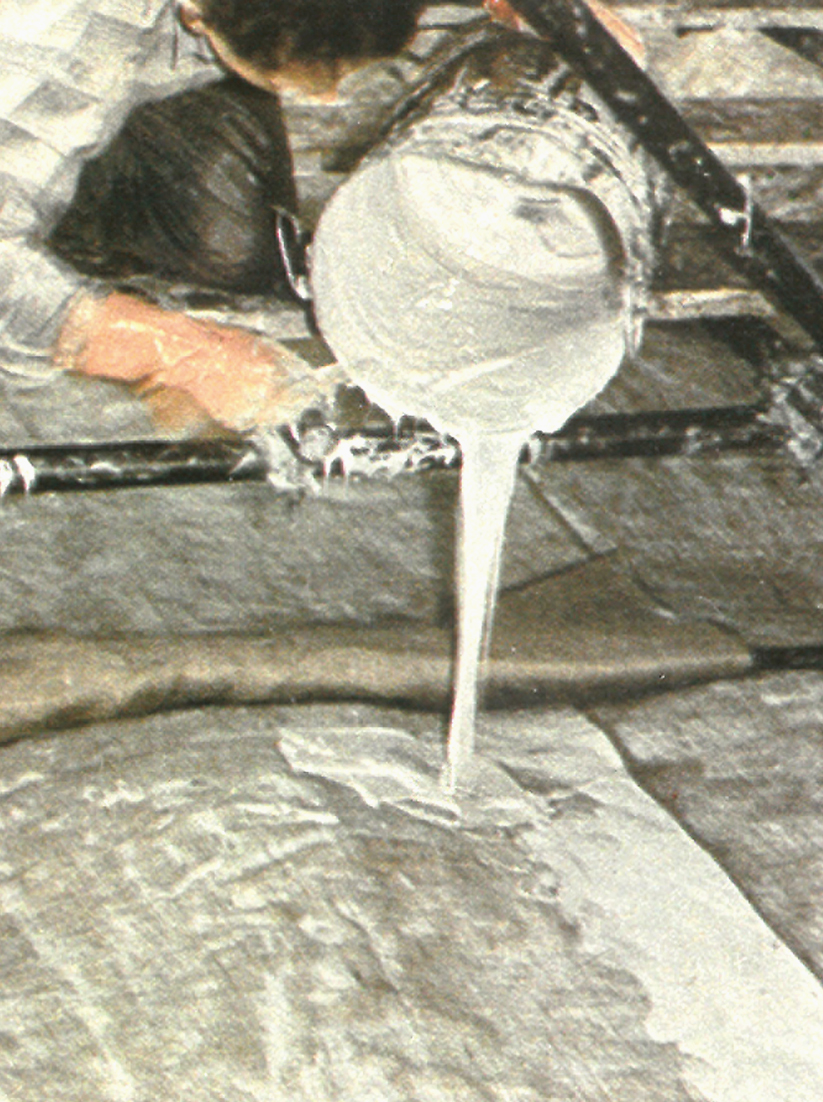

In a workshop called ‘Reading with Material,’ I gave my participants clay, string, paper, tape, felt fabric, plastic bags, wire, an old coat hanger and various other materials. I invited them to encounter their chosen material, spend time with it, ask questions about its properties.

Here’s Eve Sedgwick on texture in her book Touching Feeling:

Sedgwick could be giving us a gloss for translation here. And also of epic theatre. Brecht wanted an engaged audience, inviting an interest in function and use. How could what we see on stage (which is a translation of a kind of reality) be different?

Here’s the instruction I gave to the workshop participants when I presented them with the materials (via Sedgwick again): ‘to touch is always already to reach out, to fondle, to heft, to tap, or to enfold, and always also to understand other people or natural forces as having effectually done so before oneself, if only in the making of the textured object.’ 6

Impractically, that is unserviceably, this also leads us to ask, as Joyelle McSweeney asks: ‘What regime does a work of art appeal to? Does the work of art appeal to a sensory, generic, or interpretive regime?’ 7

I take this question as a pedagogical principle. A principle for reading. Again, what would that mean practically? To practise is to repeat an exercise.

For McSweeney: ‘Translation: the migrant of a very special nature. The filthiest medium alive.’8

Laloo, the red wife, the hitchhiker, in Bhanu Kapil’s Incubation: A Space for Monsters, is the migrant-as-monster: ‘A monster is always itinerant.’ If, as Kapil writes, ‘Sex is always monstrous,’ her speaker spits out: ‘I want to have sex with what I want to become.’ 9

And if becoming is always becoming-with, as Donna Haraway suggests, then we become monstrous in the act of translation.

The monstrous is a deviant form.

And if the monster is in some way de-formed, it draws attention to form as constitutive of its being. Etymologically, the monster shows and/or warns.

The translation-as-monster is our fear of derivation.

An experimental translation, by contrast, derives a fair bit of pleasure from deviating from the norm. Irreverently non-literal it only literalises its own demand for diversion. It is demonstrative of a process of persistent re-reading.

Which we could call a practice.

°

Jack Halberstam, in writing about disciplines, states that ‘being taken seriously means missing out on the chance to be frivolous, promiscuous, irrelevant.’ 10

In critical writing we cite to show our knowledge; our debts. To pay homage. To agree or disagree. To find lines of con- and divergence.

Translation is always a dialogue. So:

°

How do we hold another’s idea? Dearly, surely, so we can turn words into lozenges in our mouth.

When my primary reader is YOU, my reading path leads to the you I address in private or the you I imagine in a sort of shadow-play public.

Maybe reading is always the private dance of the author under the intimate gaze of the reader, or, as Rebecca Solnit writes in The Faraway Nearby: what is ‘said to total strangers in the silence of writing... is [then] recuperated and heard in the solitude of reading.’ 14

“No” is the manifesto’s supreme interjection. I accidentally typed injection. Interjections convey a sentiment. Grammatically, an interjection is unrelated to any other part of the sentence.

Anne Boyer reminds me—through reading—that ‘The no of a poet is so often a yes in the carapace of no. The no of a poet is sometimes but rarely a no to a poem itself, but more usually a no to all dismal aggregations and landscapes outside of the poem.’ 15

When we say “no” where does the negation lead us? ‘No to style,’ says Yvonne Rainer. 16 A style of negation is also a style. Style comes from stylus which is a pen. Around 1700, choreography began to mean the act of notating a dance on paper. For me, a choreography of language is also about gesture, about motion and emotion, about direction and patterns. About legible and illegible shapes. For example, how Pina Bausch’s dancers weave patterns into the leaves on the stage of her disturbing piece Bluebeard. Crunching. The women literally go up the wall. The dance makes visible a metaphor. A physical translation. So they hang, suspended, like crushed insects, dried on wallpaper.

Is this taking the movement metaphor too far? The transfer.

Translation can be a “no” to being physically re-moved from the borders of identity or nationality.

How many more metaphors for translation can we conjure up?

‘Metaphors inflate at their own risk.’18 I was told this when I made a promise I didn’t quite keep.

Ian Patterson asks us to ‘think about what happens when I read a poem which is based in an act of translation which imagines text out of one existence and into another even as it writes. Not so much translating a poem as translating the reading performance of a poem into the world of another poem. The source text here is more than a source and less than a text, or maybe the other way round, more than a text and less than a source. Or maybe neither. Maybe just a resource, or a resurgence, even an insurgence. At all events, it raises the question of what survives of the poem’s sources and what has to be destroyed, both in the writing and the reading. We might suppose that any act of reading a poem harms it: intentionally, or unintentionally, we wound, disfigure, or deface the poem as we read it because we hallucinate our sense of its sense. As Winnicott puts it in another context, “The fact is that an external object has no being for you or me except in so far as you or I hallucinate it, but being sane we take care not to hallucinate except where we know what to see.”19

What would it mean to hallucinate the (sense of the) translated object? To hallucinate ourselves?

To hallucinate is to go astray in thought.

Often when I teach, I do not know what will come out of my mouth.

Teaching is the translation of reading into a room. Another kind of thinking out loud into space, with a direct address. Into a temporary holding space for ideas. Both the avowed expert, the teacher, and the allegedly impressionable students perform that act of translation. We paraphrase a text into a supposedly more palatable prose piece. What makes a work, a language, palatable?

To call what I do translational is to take the word ending as a simile. When something is like translation it doesn’t need to be it.

If “no” is the manifesto’s pet word, then “re-” is translation’s prefix par excellence. Repeat. Return. Re-read. Re-write.

Re-, as Rita Felski and others have observed, captures a shift in our critical vocabulary that is less focused on the destructive or negating work of de- or un-. Re- can signal movement in time and space, amplification, iteration, and simultaneously memory and futurity.

In this realm of re-, translation and writing-as-reading are in a constant mirror stage of towardness and relationality.

This recognition can be joyous or judgemental.

°

Sometimes we might feel overwhelmed by a task at hand. Sometimes breathing feels heavy. The limbs might go numb. Could the tingling hands be a symptom of the itch to produce, all energy rushing to the life-sustaining organs.

Are hands not life-sustaining? What is the tingling effect of translational reading? When something goes numb it is also hyper-sensitive. Let’s add a principle to this failing, flailing manifesto.

(Isn’t translation always the putting of words into someone’s mouth,

that someone sometimes being you?)

Words can contextualise, embellish, explain. They can be raw, they can be tender, they can be violent. They can be matter of fact or they can translate matter into something else. Words force us to be nuanced.

While translation trades in words, it also encompasses, for me, the moving of material from one place to another. Which is admittedly a broad delineation. But capaciousness can be a generosity. So. Translation might mean moving a language, an idea, an image, a material (like paper or clay) to a known or unknown elsewhere, or it might mean transforming it into another form or context.

This piece, which is a kind of delirious reading in progress, will propose a sprawling and lounging understanding of translation:

translation as an inventive, generative, and often collaborative practice;

translation as a form of writing-as-reading;

and translational reading as a pedagogical tool.

Using Sara Ahmed’s terminology in her manifesto Living a Feminist Life, translation is in my ‘feminist killjoy survival kit.’1

‘And so the three things I take to the Desert Island of Obsessive Exercise are nuts for nourishment, hummus for humility, and dragon fruit for keeping the eyes alight amidst the non-variation and promise of paradise.’2

Which is another thing I put into a play. When I translate, I keep everything in play. Or at bay? Sound play, like any good tutor, imparts knowledge by osmosis.

Translation is a deeply pedagogical form. Because it teaches you to read. So here’s my manifesto for reading.

Principle 1

No to verticality. Languages and art forms don’t exist on a slope of significance.

Principle 2

No to valorising originals. Which is an old hat in its critique but bears repeating. Yes to old hats.

Principle 3

I will view translation as a process for transformation.

Principle 4

I will remain open to my own translation.

Principle 5

A translational pedagogy is a playful pedagogy.

Principle 6

A playful pedagogy is unpredictable; I won’t know where the ball will land or who, if anyone, will catch it.

Principle 7

Scratch the house style.

These almost-wise and not-quite-adamant demands serve a pragmatic truth. Which is provisional. And admits to not-knowing.

‘Not knowing,’ as Jack Halberstam suggests in The Queer Art of Failure, may in fact offer more creative, more cooperative [and] surprising ways of being in the world.’3 Translation, like a manifesto, like pedagogy, is of a delayed futurity. If this were a proper manifesto, or a classroom, I would invoke a “we,” a call for action.

What action is reading?

Taking a shower is an activity. Taking a bath professes not-doing. To write in the bath is to enter the jurisdiction of floating. Of idleness. Lisa Robertson’s she-dandy allows herself to pursue her thoughts languorously. What knowledge does leisure afford?

Working on a translation you do figure eights of reading. ‘To rush it breathlessly through does very well for a beginning. But that is not the way to read finally.’4 Virginia Woolf is speaking about the need to re-read a novel here, but her comment also resonates with our critical desire to extract, to unearth, as a means to an end.

Is parsing always in cahoots with parsimony? Avoid finality! Etc. A non-extractive reading might be one that answers in kind: not by translation into a different discourse, but by using a creative circuitry of aesthetic kinship. Writing-through-reading can mean taking it in, chewing it. Letting it percolate.

I WANT A PEDAGOGY OF PERCOLATION

In my teaching, I promote what I call ‘translational reading,’ which tries to understand a text by doing something with it.

In a workshop called ‘Reading with Material,’ I gave my participants clay, string, paper, tape, felt fabric, plastic bags, wire, an old coat hanger and various other materials. I invited them to encounter their chosen material, spend time with it, ask questions about its properties.

Here’s Eve Sedgwick on texture in her book Touching Feeling:

‘To perceive texture is never only to ask or know What is it like? nor even just How does it impinge on me? Textural perception always explores two other questions as well: How did it get that way? and What could I do with it?’5

Sedgwick could be giving us a gloss for translation here. And also of epic theatre. Brecht wanted an engaged audience, inviting an interest in function and use. How could what we see on stage (which is a translation of a kind of reality) be different?

Here’s the instruction I gave to the workshop participants when I presented them with the materials (via Sedgwick again): ‘to touch is always already to reach out, to fondle, to heft, to tap, or to enfold, and always also to understand other people or natural forces as having effectually done so before oneself, if only in the making of the textured object.’ 6

Impractically, that is unserviceably, this also leads us to ask, as Joyelle McSweeney asks: ‘What regime does a work of art appeal to? Does the work of art appeal to a sensory, generic, or interpretive regime?’ 7

I take this question as a pedagogical principle. A principle for reading. Again, what would that mean practically? To practise is to repeat an exercise.

For McSweeney: ‘Translation: the migrant of a very special nature. The filthiest medium alive.’8

Laloo, the red wife, the hitchhiker, in Bhanu Kapil’s Incubation: A Space for Monsters, is the migrant-as-monster: ‘A monster is always itinerant.’ If, as Kapil writes, ‘Sex is always monstrous,’ her speaker spits out: ‘I want to have sex with what I want to become.’ 9

And if becoming is always becoming-with, as Donna Haraway suggests, then we become monstrous in the act of translation.

The monstrous is a deviant form.

And if the monster is in some way de-formed, it draws attention to form as constitutive of its being. Etymologically, the monster shows and/or warns.

The translation-as-monster is our fear of derivation.

An experimental translation, by contrast, derives a fair bit of pleasure from deviating from the norm. Irreverently non-literal it only literalises its own demand for diversion. It is demonstrative of a process of persistent re-reading.

Which we could call a practice.

°

Jack Halberstam, in writing about disciplines, states that ‘being taken seriously means missing out on the chance to be frivolous, promiscuous, irrelevant.’ 10

In critical writing we cite to show our knowledge; our debts. To pay homage. To agree or disagree. To find lines of con- and divergence.

Translation is always a dialogue. So:

L—We illustrate, we dangle another voice off the end of our critical fish hook. Which might be a distraction. And an ethical conundrum.

S—What if the hook were not for catching fish but a cyborgian pirate prosthesis? The prosthesis is an extension of the body. ‘My body is an extension of my body’. 11 ‘That’s kind of like the dumb myth of freedom; go make our own laws and control our own ship.’ 12

L—Which is the utopian dream...

S—Do we dream of the ability to think endlessly, without ever reaching the point of exhaustion?

L—Exhaustion has its own internal rhythm. Anxiety is the carefully trodden path of my own pleasure.

S—Anxiety is a translational topos. That is: topology is the interrelationship and arrangement of constituent parts. The properties of an object that stay the same under the constant stretching, twisting, crumpling, and bending.

L—Is that what you mean by understanding a text by ‘doing something with it’.

S—Force yourself to think onto the page or go off it. So you can be off. Be beside the point.

L—QUOTE ‘Crusting, pushing, shifting, sliding through itself. Shearing away. [...] Something that huffs itself, form evaporating, changing, moulding’ 13

UNQUOTE

S—If criticism is obsessed with quotation, a manifesto for reading ought to be a barrage. I don’t want to bombard you.

L—Oh, please bombard me.

°

How do we hold another’s idea? Dearly, surely, so we can turn words into lozenges in our mouth.

When my primary reader is YOU, my reading path leads to the you I address in private or the you I imagine in a sort of shadow-play public.

Maybe reading is always the private dance of the author under the intimate gaze of the reader, or, as Rebecca Solnit writes in The Faraway Nearby: what is ‘said to total strangers in the silence of writing... is [then] recuperated and heard in the solitude of reading.’ 14

“No” is the manifesto’s supreme interjection. I accidentally typed injection. Interjections convey a sentiment. Grammatically, an interjection is unrelated to any other part of the sentence.

(You see, this is still a sort of manifesto for reading by making my reading manifest)

Anne Boyer reminds me—through reading—that ‘The no of a poet is so often a yes in the carapace of no. The no of a poet is sometimes but rarely a no to a poem itself, but more usually a no to all dismal aggregations and landscapes outside of the poem.’ 15

When we say “no” where does the negation lead us? ‘No to style,’ says Yvonne Rainer. 16 A style of negation is also a style. Style comes from stylus which is a pen. Around 1700, choreography began to mean the act of notating a dance on paper. For me, a choreography of language is also about gesture, about motion and emotion, about direction and patterns. About legible and illegible shapes. For example, how Pina Bausch’s dancers weave patterns into the leaves on the stage of her disturbing piece Bluebeard. Crunching. The women literally go up the wall. The dance makes visible a metaphor. A physical translation. So they hang, suspended, like crushed insects, dried on wallpaper.

Is this taking the movement metaphor too far? The transfer.

‘No to moving or being moved.’17

Translation can be a “no” to being physically re-moved from the borders of identity or nationality.

How many more metaphors for translation can we conjure up?

‘Metaphors inflate at their own risk.’18 I was told this when I made a promise I didn’t quite keep.

Ian Patterson asks us to ‘think about what happens when I read a poem which is based in an act of translation which imagines text out of one existence and into another even as it writes. Not so much translating a poem as translating the reading performance of a poem into the world of another poem. The source text here is more than a source and less than a text, or maybe the other way round, more than a text and less than a source. Or maybe neither. Maybe just a resource, or a resurgence, even an insurgence. At all events, it raises the question of what survives of the poem’s sources and what has to be destroyed, both in the writing and the reading. We might suppose that any act of reading a poem harms it: intentionally, or unintentionally, we wound, disfigure, or deface the poem as we read it because we hallucinate our sense of its sense. As Winnicott puts it in another context, “The fact is that an external object has no being for you or me except in so far as you or I hallucinate it, but being sane we take care not to hallucinate except where we know what to see.”19

What would it mean to hallucinate the (sense of the) translated object? To hallucinate ourselves?

To hallucinate is to go astray in thought.

Often when I teach, I do not know what will come out of my mouth.

Teaching is the translation of reading into a room. Another kind of thinking out loud into space, with a direct address. Into a temporary holding space for ideas. Both the avowed expert, the teacher, and the allegedly impressionable students perform that act of translation. We paraphrase a text into a supposedly more palatable prose piece. What makes a work, a language, palatable?

To call what I do translational is to take the word ending as a simile. When something is like translation it doesn’t need to be it.

If “no” is the manifesto’s pet word, then “re-” is translation’s prefix par excellence. Repeat. Return. Re-read. Re-write.

Re-, as Rita Felski and others have observed, captures a shift in our critical vocabulary that is less focused on the destructive or negating work of de- or un-. Re- can signal movement in time and space, amplification, iteration, and simultaneously memory and futurity.

In this realm of re-, translation and writing-as-reading are in a constant mirror stage of towardness and relationality.

This recognition can be joyous or judgemental.

°

Sometimes we might feel overwhelmed by a task at hand. Sometimes breathing feels heavy. The limbs might go numb. Could the tingling hands be a symptom of the itch to produce, all energy rushing to the life-sustaining organs.

Are hands not life-sustaining? What is the tingling effect of translational reading? When something goes numb it is also hyper-sensitive. Let’s add a principle to this failing, flailing manifesto.

Principle 8

I am willing to care. And I am willing to show it.

NOTES

1 Sara AHMED, Living a Feminist Life

Duke University Press, 2017

2 Sophie SEITA, The Gracious Ones

[a work-in-progress]

3 Jack HALBERSTAM, The Queer Art of Failure

Duke University Press, 2011

4 Virginia WOOLF, ‘On Re-Reading Novels’

in Genius & Ink, TLS Books, 2019

5 Eve SEDGWICK,

Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy

Performativity, 2003

6 Eve SEDGWICK (again)

7 Joyelle McSWEENEY,

‘Translation, the Slavish Mould,

the Filthiest Medium Alive’

in Joyelle McSWEENEY

& Johannes GORANSSON,

Deformation Zone, Ugly Duckling Presse, 2012

8 Joyelle McSWEENEY (again)

9 Bhanu KAPIL, Incubation: A Space for Monsters

Leon Works 2006

10 Jack HALBERSTAM, The Queer Art of Failure

Duke University Press, 2011

11 Barbara BROWNING,

The Gift (or, Techniques of the Body)

Coffee House Press, 2017

12 Kathy ACKER,

The Last Interview; & Other Conversations

(ed.) A. Scholder & D. A. Martin

Melville House, 2018

13 Joyelle McSWEENEY (again)

14 Rebecca SOLNIT, The Nearby Faraway

Granta, 2014

15 Anne BOYER, ‘No’

in A Handbook of Disappointed Fate

Ugly Duckling Presse, 2018

16 Yvonne RAINER, ‘No Manifesto’

in Feelings & Facts: A Life

MIT Press, 2006

17 Yvonne RAINER (again)

18 Iain SINCLAIR, Lud Heat

Skylight Press, 2012

19 Ian PATTERSON, ‘Langue-in-Cheek:

Reading & Writing Between the Lines’

Thinking Verse, 4.2., 2015

1 Sara AHMED, Living a Feminist Life

Duke University Press, 2017

2 Sophie SEITA, The Gracious Ones

[a work-in-progress]

3 Jack HALBERSTAM, The Queer Art of Failure

Duke University Press, 2011

4 Virginia WOOLF, ‘On Re-Reading Novels’

in Genius & Ink, TLS Books, 2019

5 Eve SEDGWICK,

Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy

Performativity, 2003

6 Eve SEDGWICK (again)

7 Joyelle McSWEENEY,

‘Translation, the Slavish Mould,

the Filthiest Medium Alive’

in Joyelle McSWEENEY

& Johannes GORANSSON,

Deformation Zone, Ugly Duckling Presse, 2012

8 Joyelle McSWEENEY (again)

9 Bhanu KAPIL, Incubation: A Space for Monsters

Leon Works 2006

10 Jack HALBERSTAM, The Queer Art of Failure

Duke University Press, 2011

11 Barbara BROWNING,

The Gift (or, Techniques of the Body)

Coffee House Press, 2017

12 Kathy ACKER,

The Last Interview; & Other Conversations

(ed.) A. Scholder & D. A. Martin

Melville House, 2018

13 Joyelle McSWEENEY (again)

14 Rebecca SOLNIT, The Nearby Faraway

Granta, 2014

15 Anne BOYER, ‘No’

in A Handbook of Disappointed Fate

Ugly Duckling Presse, 2018

16 Yvonne RAINER, ‘No Manifesto’

in Feelings & Facts: A Life

MIT Press, 2006

17 Yvonne RAINER (again)

18 Iain SINCLAIR, Lud Heat

Skylight Press, 2012

19 Ian PATTERSON, ‘Langue-in-Cheek:

Reading & Writing Between the Lines’

Thinking Verse, 4.2., 2015

SEITA’s ‘LET IT PERCOLATE’

is excerpted from BRICKS FROM THE KILN #4

Edited by Natalie FERRIS,

Bryony QUINN,

Matthew STUART

& Andrew WALSH‐LISTER

is excerpted from BRICKS FROM THE KILN #4

ORDER HERE

Edited by Natalie FERRIS,

Bryony QUINN,

Matthew STUART

& Andrew WALSH‐LISTER

Featuring works by Helen MARTIN;

Sophie COLLINS;

Don MEE CHOI;

Kate BRIGGS;

Phil BABER;

Joyce DIXON;

Florian ROITHMAYR;

Jen CALLEJA;

J.R. CARPENTER;

Edgar WIND;

Rebecca COLLINS;

Naomi PEARCE;

Karen Di FRANCO;

James BULLEY;

Safi MAFUNDIKWA;

Natalie FERRIS;

Matthew STUART;

James LANGDON;

Bryony QUINN;

Peter NENCINI;

Sophie SEITA;

Caroline BERGVALL;

Seb McCLAUCHLAN;

& Maria FUSCO

Sophie SEITA is an interdisciplinary artist and researcher whose practice spans performance, lecture-performance, poetry, translation, installation and video. Throughout her practice, poetry offers a specific form of thinking beyond genre and media boundaries, a kind of polyvocal, opulent research into the ways we are choreographed by language. A commitment to queer-feminist politics, collaboration and experimental aesthetics underpins all her work. Her performances and readings have been presented at the Royal Drawing School, Art Night 2018 and 2019, the Royal Academy, Bold Tendencies, Parasol Unit, Raven Row (all London), the Arnolfini (Bristol), La MaMa Galleria, Company Gallery, Issue Project (all NYC), Cité Internationale des Arts (Paris), SAAS-Fee Summer Institute of Art (Berlin), Taller Bloc (Santiago, Chile), Kunsthalle (Darmstadt, Germany), Kettle’s Yard (Cambridge) and elsewhere.

She is the author of (most recently) The Gracious Ones (Earthbound Press, 2020), Provisional Avant-Gardes (Stanford University Press, 2019) and the artist books Little Enlightenement Plays (Pamenar, 2020) My Little Enlightenment: A Lecture Performance (Other Forms, 2019), Little Enli and Transpositions (2018), the translator of Uljana Wolf’s Subsisters: Selected Poems (Belladonna*, 2017), for which she received a PEN Grant; and the editor of The Blind Man (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2017) named one of the Best Art Books of 2017 by The New York Times. Other work can be found in Bomb, Urgency Reader / Queer.Archive.Work, Ma Bibliothèque, Manifold: Experimental Criticism, Rupert Journal, The Times Literary Supplement, The White Review, Emergency Index, Hotel and 3:AM.