PORTRAIT/

Self-PORTRAIT

Lee FRIEDLANDER

EXCERPTS FROM THE FRIEDLANDER FIRST 50

With a career spanning seven decades, renowned American photographer Lee Friedlander has produced an unrivaled photographic output documenting seemingly every aspect of the American “social landscape” (a term Friedlander coined), with a specific focus on creating books. “Books are my medium,” Friedlander has been quoted as saying. Friedlander First Fifty—a new publication from SPQR Editions and Haywire Press—provides an inside look at Friedlander’s first fifty books, featuring extensive commentary directly from Friedlander on his own work. The book contains photographs from each of the first fifty books, as well as descriptions, publication information and—most notably—interviews with Friedlander and his wife, Maria, conducted by Friedlander’s grandson, Giancarlo, and daughter, Anna, who together co-published the book. The result is the most personal and candid look at Friedlander’s life and career to date, as told to his own family. Published over a fifty year period, from 1969-2018, the first fifty books describe the entirety of Friedlander’s subject matter—from jazz musicians to factory workers to monuments to television screens—and genres—from self-portraits to street photographs to nudes to landscapes. Hotel is delighted to support this publication, and here feature an exclusive selection oftexts and photographs carried therein.

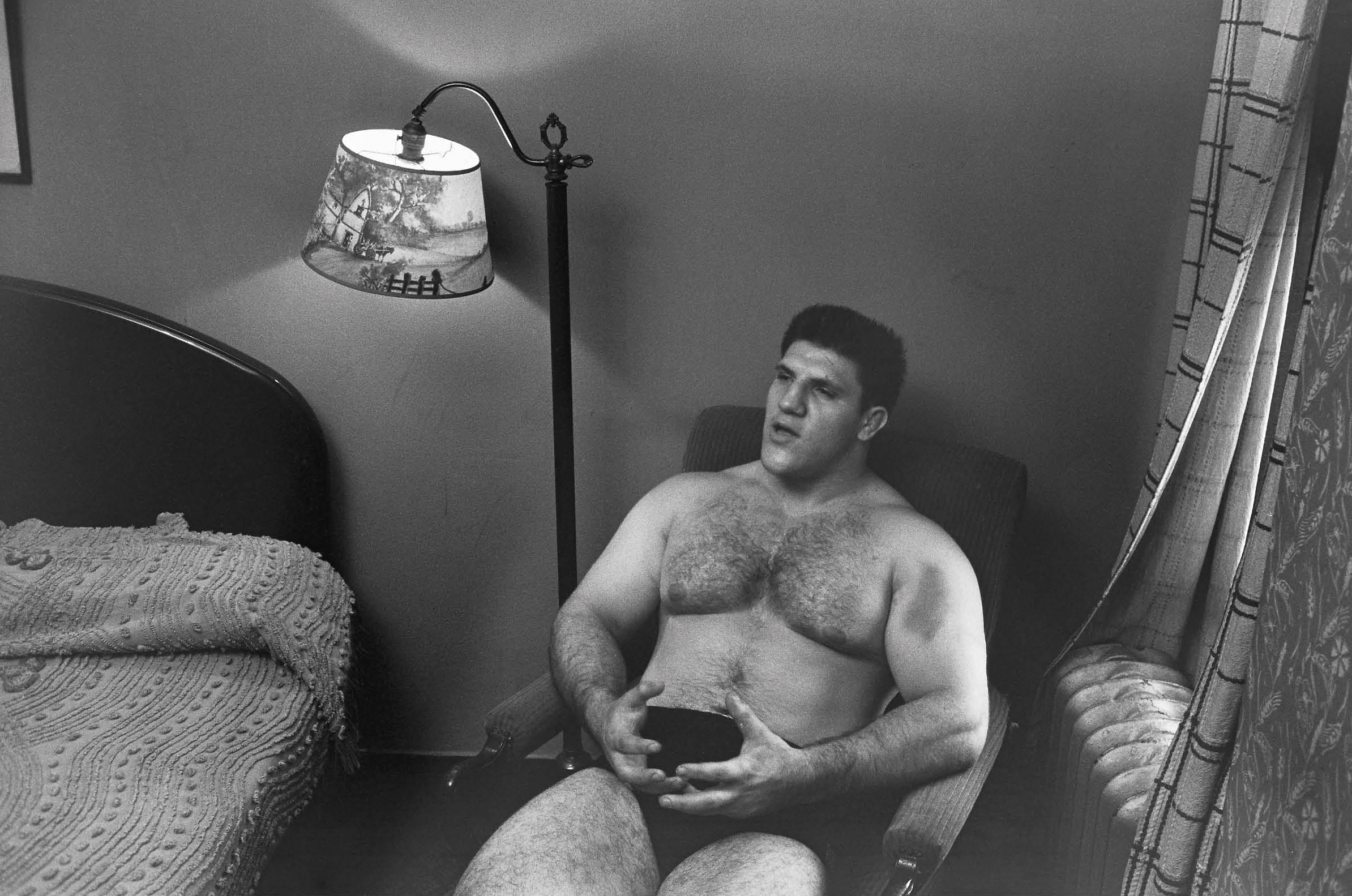

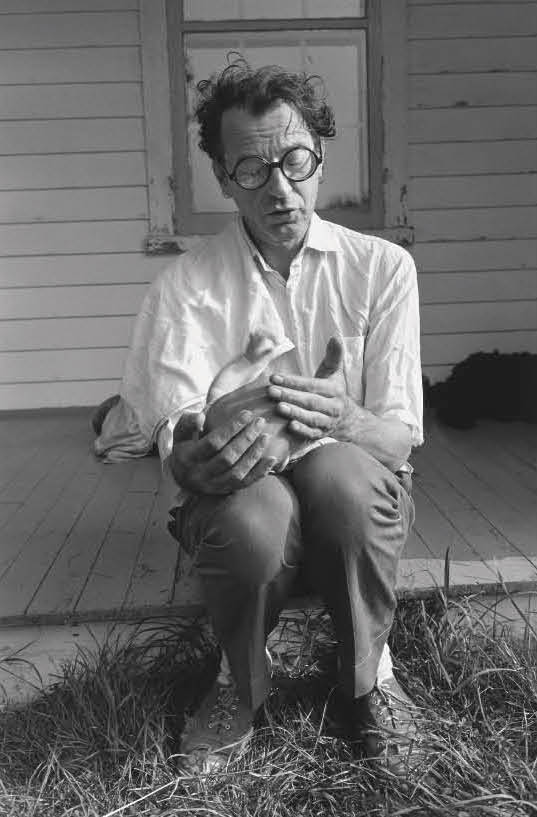

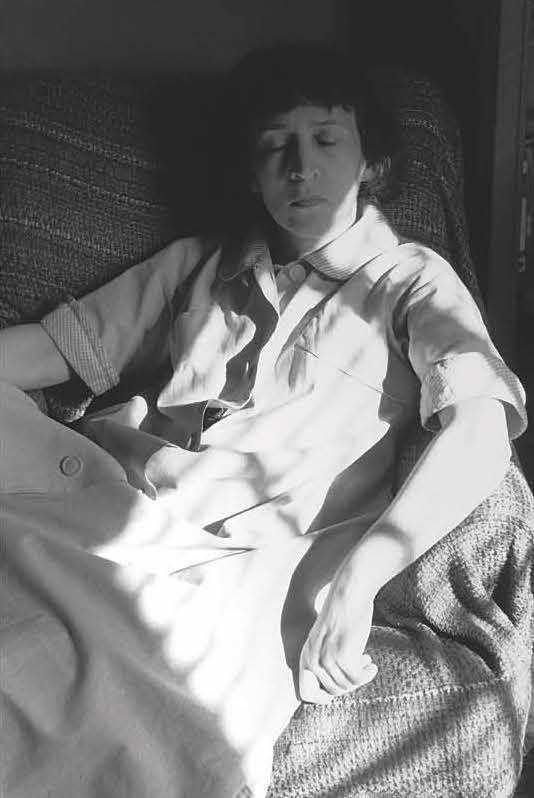

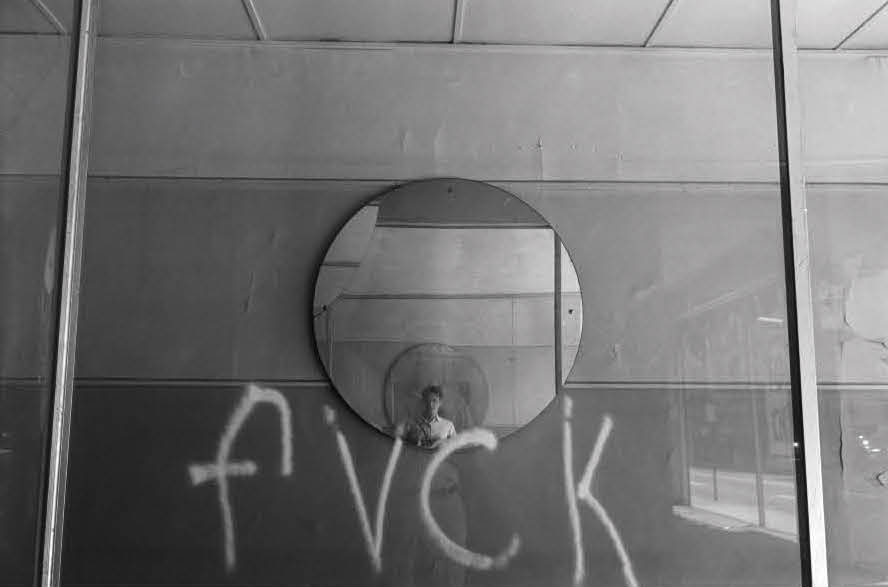

i. Portraits (1985)

“THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF MY VERY DEAR FRIEND GARRY WINOGRAND” — L.F.

Portraits marks Friedlander’s first monograph in which he turns his camera exclusively on human subjects, both famous—jazz pianist Count Basie, writer Walker Percy, fellow photographer Diane Arbus—and unknown. From the publisher: “Portraits presents a little-known aspect of the photographer’s work, but the portraits have the wry, warm, offbeat quality that is essential Friedlander. The sitters are seen in familiar, usually simple settings, but an instinctive photographic vision has caught them in unusual perspectives or lighting, with fleeting expressions or casual postures that are richly suggestive of contexts past and future.

Lee: I remember I was walking down the street and she was walking up the street and I picked up my camera and I waited for her to come and she stopped right in front of me, I took the picture, and she walked off. Never said a word. Giancarlo: So was she coming to get her picture taken? Lee: No! I didn’t know her. I don’t know who she is. It was as if we were meant for each other, do you know what I’m saying? Giancarlo: Yes. Lee: Sometimes you’re lucky.

Anna: You’re known for self-portraits—is it very different for you to take portraits?

Lee: Oh yes.

Anna: How so?

Lee: Well, I can make myself do anything I want. [laughing]

Anna: With portraits you have to work with what you’re given.

Lee: That’s it.

“Her close little sitting-room was prepared for a visit, and there was a portrait of her son in it which, I had almost written here, was more like than life: it insisted upon him with such obstinacy, and was so determined not to let him off.”

— Charles Dickens, Bleak House

Anna: How’d you decide who to include in this book?

Lee: Whim—like all the other decisions I’ve ever made.

Giancarlo: R.B. Kitaj wrote something in his foreword that I like:

These faces are imprinted vestiges of Friedlander’s brushes with life, little fossil imprints, natural like that, without the many interventions caused by hand-art.

Lee: Boy that’s complicated. I think that’s fantastic.

Giancarlo: It does kind of sound right.

Lee: It sure does sound right. You kind of come upon something quickly, and it renders itself fast. Whereas with hand-art you have more time. I think it is very, very clear, better than ten sentences.

Giancarlo: Did you have any friends who asked you not to take their picture? Lee: Usually after I’ve done it.

Giancarlo: And what do you do after they say that? Lee: I say... you know... [mumbles and shrugs] Giancarlo: I guess it had already happened. Lee: Very rarely thoygh. A 35mm camera is so tiny. Look at it in that picture I have of Garry. It looks like a toy. It doesn’t look like something dangerous. But Helen Levitt didn’t like it that I took her picture. Anna: Really?

Lee: Oh yes, she yelled at me.

Giancarlo: Did you shrug after you took it? Lee: Well, I didn’t take a second one. [laughter]

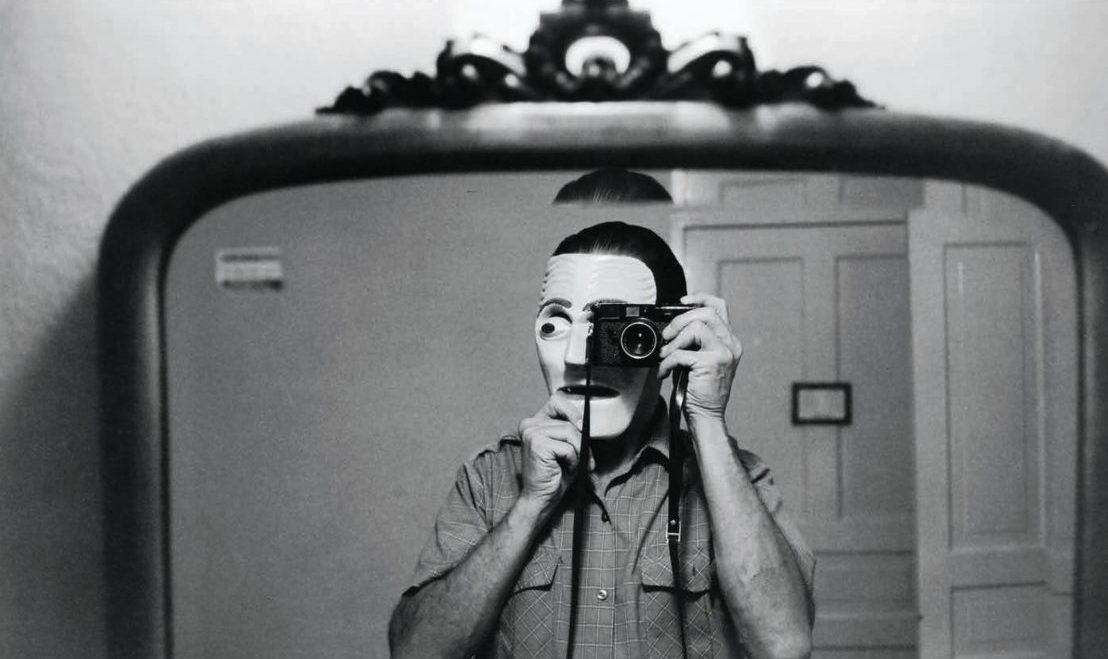

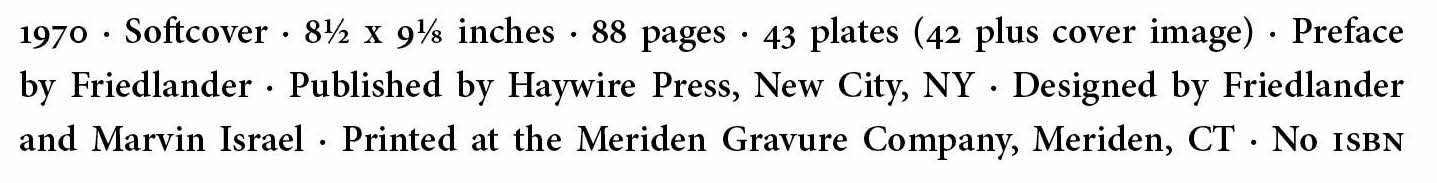

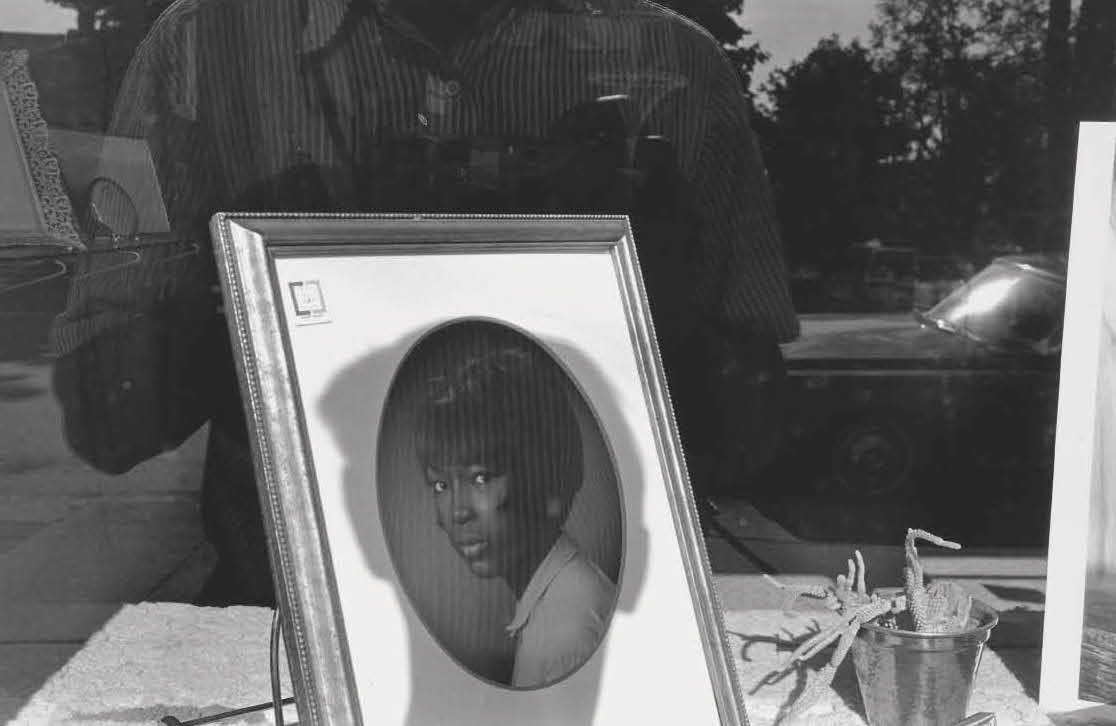

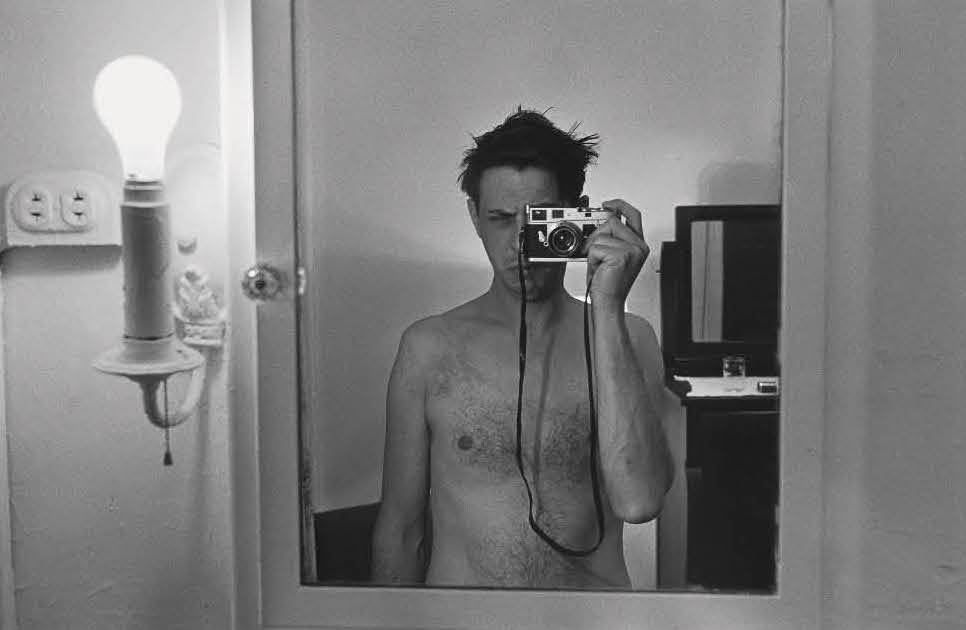

ii. Self-Portrait (1970)

Self Portrait is Friedlander’s first monograph, self-published by Haywire Press. Inserting himself into the world in various ways—his face peering out from behind a trophy, the specter of his enlarged silhouette looming over a doorway, his reflection in a dirty mirror, and perhaps most famously, the shadow of his head cast onto a woman walking in front of him on the street—Friedlander decidely challenges and reinvents the form of the self-portrait. The result is a body of work that is alternatively mischevious, spooky, defiant, and even lighthearted, but never predictable. In his introduction, Friedlander writes: “They began as straight portraits but soon I was finding myself at times in the landscape of my photography. I might call myself an intruder.”

Anna: So since it was self-published, how did you sell the book back then? Maria: It was my job to sell them. Every time I went to the city I took two or three copies of them with me. I went to bookstores and galleries that sold books and sometimes they took a copy or two. I liked to come home with an empty bag. We charged $5 a copy.

Anna: How much did it cost to print? Lee: Probably $3 a copy.

Maria: Our best customer was Witkin gallery. They asked me once if Lee would sign the next bunch they purchased—they usually bought them in groups of ten—and Lee said no, as if they were asking too much of him.

Lee: They were only $5. Maria: I wanted to sell them. Lee: They could’ve bought them. Maria: Yes, but after that they didn’t.

Giancarlo: So this was your first monograph?

Lee: Yes. The title is self-evident don’t you think?

Giancarlo: I do. I remember you saying that with Self Portrait you made a book that nobody else would publish. Lee: Well I figured, who’s going to publish a bunch of pictures of myself? Giancarlo: But yourself.

Lee: Exactly. I thought it’s the one book I would never find a publisher for, they’re all pictures of me. So I created Haywire Press.

Giancarlo: So Self Portrait is self-published.

Maria: that was quite courageous, to make a book of yourself. Giancarlo: That was kind of gutsy.

*

Lee: I said to my friend Marvin Israel [art director], “Can you design it for me?” And he said, “No, you already did it.” He liked it because the typewriter type was, you know, like Self Portrait.

Giancarlo: Wait, what do you mean it’s like Self Portrait? Lee: Using the typewriter is like doing something yourself.

Giancarlo: True.

Maria: I had done the typing on our old typewriter.

Giancarlo: So grandma actually typed the cover text?

Maria: Yes, I designed it, because Lee was going to take it to show it around and we didn’t have anything else.

[laughter]

Anna: I see there are no page or plate numbers.

Maria: Yes, I couldn’t type on top of the photographs!

Lee FRIEDLANDER, born in 1934, began photographing the American social landscape in 1948. With an ability to organize a vast amount of visual information in dynamic compositions, Friedlander has made humorous and poignant images among the chaos of city life, dense natural landscape, and countless other subjects. Friedlander is also recognized for a group of self-portraits he began in the 1960s, reproduced in Self Portrait, an exploration that he turned to again in the late 1990s, and published in a monograph by Fraenkel Gallery in 2000. Included among the many monographs designed and published by Friedlander himself are Sticks and Stones, Lee Friedlander: Photographs, Letters From the People, Apples and Olives, Cherry Blossom Time in Japan, Family, and At Work. Starting in 2017, the artist and Yale University Press released an ambitious six-book suite collectively titled The Human Clay—a sweeping collection street and environmental portraits culled and edited by Friedlander from his extensive archive, many not previously published. Friedlander’s work was included in the highly influential 1967 New Documents exhibition, curated by John Szarkowski at the Museum of Modern Art. In 2005, Friedlander was the recipient of the prestigious Hasselblad Award as well as the subject of a major traveling retrospective and catalog organized by the Museum of Modern Art. In 2010, the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York exhibited the entirety of his body of work, America by Car. In 2017, Yale University Art Gallery exhibited and published the some of his earliest work, 1957 photographs of participants of the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom in Washington, D.C. His work is held by major collections including Art Institute of Chicago;, George Eastman Museum; The Metropolitan Museum of Art; The Museum of Modern Art; The National Gallery of Art; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; the Whitney Museum of American Art, among many others.

All photographs © Lee Friedlander, 1970; 1985.

All interview citations are excerpted from Friedlander First Fifty, © Haywire Press, 2019.

Hotel would like to thank Anna Roma for her editorial assistance.

All interview citations are excerpted from Friedlander First Fifty, © Haywire Press, 2019.

Hotel would like to thank Anna Roma for her editorial assistance.