‘I Really Love a Lot of Paper’

HOTEL & REKTO:VERSO editors talk to

Kenneth GOLDSMITH

Kenneth Goldsmith (born in 1961 in Freeport, New York) is an American poet. He is the founding editor of UbuWeb and is a senior editor of PennSound, at the University of Pennsylvania, where he also teaches. He hosted a weekly radio show at WFMU from 1995 until June 2010, and has published ten books of poetry, notably Fidget (2000), Soliloquy (2001), Day (2003) and his American trilogy, The Weather (2005), Traffic (2007), and Sports (2008). He is the author of a book of essays, Uncreative Writing: Managing Language in the Digital Age (2011) and, in 2013, was appointed the Museum of Modern Art’s first poet laureate. His writing has been called some of the most “exhaustive and beautiful collage work yet produced in poetry” by Publishers Weekly. His most recent work includes Capital: New York, Capital of the 20th Century, a kaleidoscopic assemblage and poetic history of New York, and Wasting Time on the Internet, a text which contends that our digital lives are remaking human experience. In 2015, he collaborated with Jean Boîte éditions to produce Theory, which offers an unprecedented reading of the contemporary world in 500 texts—from poems and musings to short stories, printed on a 500 page ream of paper—and Against Translation, an essay published simultaneously in English, French, Spanish, German, Chinese, Japanese, Russian and Arabic.

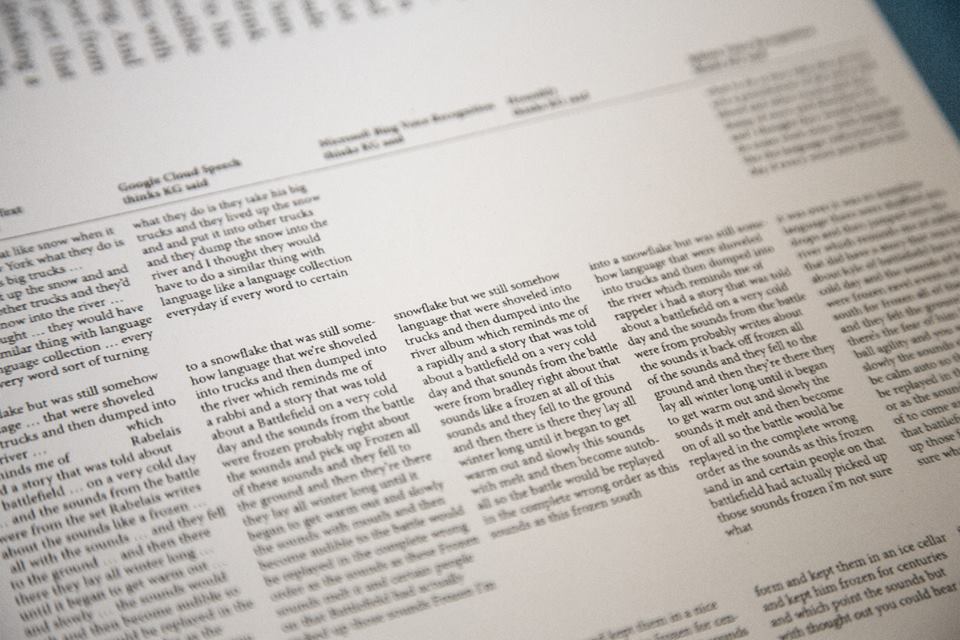

Shortly before speaking with Hotel, Kenneth Goldsmith gave a lecture to students from both the PXL-MAD School of Arts in Hasselt, and the Masters in Western Literature at the University of Leuven. This lecture along with every other talk, workshop, discussion and interview undertaken by Goldsmith during his week-long residency across the two institutions was recorded, transcribed and turned into a book entitled The PXL-MAD Lectures. Published by het balanseer as a limited run—edited by Arne De Winde, Evelin Brosi, Kris Latoir, and designed by Oliver Ibsen—The PXL-MAD Lectures launched at the closing lecture that Goldsmith gave at the end of his residency at the Pieter de Somer Aula in Leuven

Hotel was fortunate to be able to collaborate with Gert-Jan Meyntjens—from Belgian magazine Rekto:Verso—where an alternative translation of this conversation will be published.

Shortly before speaking with Hotel, Kenneth Goldsmith gave a lecture to students from both the PXL-MAD School of Arts in Hasselt, and the Masters in Western Literature at the University of Leuven. This lecture along with every other talk, workshop, discussion and interview undertaken by Goldsmith during his week-long residency across the two institutions was recorded, transcribed and turned into a book entitled The PXL-MAD Lectures. Published by het balanseer as a limited run—edited by Arne De Winde, Evelin Brosi, Kris Latoir, and designed by Oliver Ibsen—The PXL-MAD Lectures launched at the closing lecture that Goldsmith gave at the end of his residency at the Pieter de Somer Aula in Leuven

Hotel was fortunate to be able to collaborate with Gert-Jan Meyntjens—from Belgian magazine Rekto:Verso—where an alternative translation of this conversation will be published.

Hotel

Kenneth Goldsmith

Hotel

Rekto:Verso

[sighs]

In today’s world do you see reading and writing as public acts?

Kenneth Goldsmith

I think most reading and writing are public because of social media and digital reading tends to be read in public, everybody is reading on the street and in the subway, and on the buses, and on the trains, and they’re also writing in public, you know, and so the idea of the writer’s studio, I think, has been exploded.

Hotel

Do you feel writing in public in this way marks a new development in the history of literature?K.G.

Yeah, I mean, it’s hard to [laughs] when else was that done? You know, in such a way? No, I mean it really is new. I mean you’ve always had artists that are sketching the city out in public, you know plein air painters, but writing has always been done, in your atelier. So I think it’s being written and broadcast publically and I think it’s been read publically in a very big way.

Rekto:Verso

Does that change the meaning of readership?K.G.

Well, you know reading is active now. I think it’s skimming, I think it’s harvesting, I think it’s scraping, I think it’s manipulating, I think it’s spamming, which by the way are also forms of writing. So, reading has now become an active thing, instead of a passive thing. The words don’t just come to you, they come and then you do something with them. I don’t want to say this prescriptively because I think we do quietly read novels, privately, but, I’m interested in an active act that demolishes the division between reading and writing. It would not be recognised previously as being reading or writing, but I think it’s happening and I think it needs to be acknowledged.Hotel

You talk variously about these different ways of playing with text as you read—“skimming, parsing, grazing, bookmarking, formalizing, and spamming language.” You have talked a lot about how that has changed the experience of reading and then in many ways you appear to respond to that same change with your writing, have there also been changes in the way we think about other traditional roles that facilitate reading? Does it alter the role of the publisher, the curator, the bookseller as well? Do you see their roles changing also?K.G.

[sighs]

Well, ten years ago I would have said absolutely. They’re demolished, we’re all self-publishing, we’re all blogging, but I think that turned out to be a disaster and I actually think that. I remember thinking ten or fifteen years ago that mainstream media, like the New York Times would have no place in the future because we’d be reporting and creating our own news and we see where that went and what then happened and they said actually in the first quarter after the Trump election or running up to it the New York Timesgained a record number of subscribers, because people are so tired of all that. What began as utopian turned very very dystopian, and, as a weird result, the verticals such as, say in New York where I live, things like the New York Times and The New Yorker, or in Britain The Guardian are much stronger than they ever were. We thought ten years ago that that was going to be the end of them and it turns out…err...I think democracy [laughs]: democratic publishing was great in concept, but very, very bad in practice.Hotel

Do you think people are calling out for gatekeepers?K.G.

I think it’s necessary, I just think it’s… I don’t think people are good enough. I also think that people get tired of finally working for free, and I think if you’re paying somebody they’re going to do a better job. Somebody’s being held accountable. When I wrote for The New Yorker, the editing was so good, was such a high level, somebody was getting paid and I’ve never had such good editing as I did with The New Yorker and I was working with not the top editors, believe me, I was working with the very low level editors who were unbelievable and as a result the writing was good. They challenged me on everything, every vagary, everything that might not be fact, I was challenged. By the time I was done it was not a blogpost, what I gave them might have actually been a blog post, but what came out was something else. So, yeah, I’m okay with gatekeepers.

“I’m fascinated by the grid, that holds the [internet] together and then the organic flesh and emotion that’s hung upon that grid, which is a fucking mess, and it’s dripping, but it’s held in place by a grid and it’s always the two, between the organic and the architectural, that is giving it a lot of zing... because if it was just architecture—the way computers used to be - you’d be like “ah, that’s just a machine,” and if it’s all just like an emotion, then it’s something else, but it’s a combination of the two...”

Rekto:Verso

I wanted to ask a more specific question, because we’re talking also about publishing now. I’m very interested in your work with Jean Boîte editions and I was wondering, how did you come to collaborate with them, and why them, and does the fact that they are a French publisher play some kind of role? It seemed interesting to me that you first published Theory in French.

K.G.

The first edition actually was done by the Jeu de Paume. Matthew Copeland, the curator, had done a series of books with the Jeu de Paume and the first one was a bi-lingual, very rough, early edition of Theory that Jeu de Paume published. I don’t remember how Jean Boîte got in touch [laughs] - Oh, they sent me that gorgeous Google dictionary, you know that big book that they did and, I had been reading about it on the web. and when they sent it to me I was like “Oh my God, these guys did this, this is incredible” and I thought they were very serious. They did such beautiful work for me, beyond what I thought they were going to be able to do. I think they’re very serious and I’ve become very devoted to them. I don’t know about France. We seem to get along well, France and I. I don’t really understand that, other than I also know that France likes Woody Allen so maybe they like Jewish New Yorkers.Rekto:Verso

And then related, I was wondering if you could say a little bit more about the form of Theoryand also maybe Against Translation?K.G.

I love paper you know, and I really love a lot of paper. We have a big stationary store called Staples in the US, which is just a monstrous place, but whenever I walk in there I feel like I’m in heaven. They have everything. They have photocopy machines and they have paper and they have pens and they have tape and they have rulers and all the things I love; I think it’s the best art supply store I’ve ever been in. And when I go in I see these giant wrapped up reams of paper and I think they’re very beautiful. But I took the idea from another artist, an older concrete poet called Aram Saroyan had actually done a ream of paper, and, I can’t remember what he’d put on it, I think maybe the word pages—I only saw pictures of it on the web—and I thought ah that’s such a cool idea, such a great book, but Aram later told me that they were all blank pages, it was a totally different project. It was very difficult for them to produce it because they all had to be handmade, like [laughs] they had to get a, they had to print the stacks of paper and then make them neat, then some guy had to go fold the paper around it to make it and then put stickers on it to make it look like a ream of paper. I just really loved that idea. I like industrial… I figured my writing is very industrial and I want it to look industrial. And I had also just come off this big project called Printing out the Internet, which was another giant paper project, and the third one that was done at the Kunsthall in Dusseldorf about printing out pirate JSTOR materials in tribute to the hacktivist called Aaron Scwartz. So, again, I’m interested in the accumulation of things and I’m interested in the materiality of language and how we can morph things from language to image to artefact and, ultimately, with something like Printing out the Internet, to spectacle. I’m interested in those transformations constantly and I thought, you know, wow, I want to do a ream of paper with all sorts of little things that I had just been writing and collecting, and the next iteration of that I want to do is actually just do a regular book of it, because the problem is that nobody read it.Rekto:Verso

I have it but...

K.G.

But you don’t want to read it, it’s too nice.Rekto:Verso

You don’t want to open it.

K.G.

Some people buy two, because they’re not expensive. I also wanted them to be really cheap so some people buy two, one to open one to just have. But I think it’s better as you know a thing to have. Against Translation was really their [Jean Boîte’s] idea. I had just written this funny little essay and it was their idea to translate it into eight languages. Which I thought was brilliant. I hadn’t had that idea, it was them. And I thought that’s amazing, that’s great. So they went and had it translated into all these languages and made these little books out of it. I mean, it’s really smart what they do and I think they produce things beautifully and think that they have really good ideas and when somebody tells me a really good idea that I hadn’t thought of I think, well, we should do that. I mean, I’m unoriginal anyway. I’m happy to take anybody else’s idea.Hotel

Thinking more broadly about the production of physical objects, you talked earlier in the lecture about labour and I think that’s an interesting consideration in response to your work. Across your work you have drawn from conceptual art practices in developing the notion of uncreative writing and you often quote Sol LeWitt for whom “the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work.” But with the work you actually produce, especially with the work that involves transcription, I feel that actually the production is quite important. Take Day, for example, yes there is a concept, but it took you over a year to type. Where do you see the role of labour in relation to your work?

K.G.

Well, I think that one thing that I like about conceptual writing is the materialisation of ephemeral ideas. It really didn’t stay conceptual; it always got realised, which is different than potential literature, say Oulipo, where it is always potential: we have some great ideas but not many of them were realised, but the ones that were realised were incredible that they were realised. I look at Perec’s books, and I go, wow, I’m so glad somebody took that thing and did that because look at this thing! I think that was really important not to just keep it like Yoko-Ono-esque-conceptual besides that had sort of already been done, what’s the point of that really? But to actually work with the material, to draw out and accentuate the materiality of language in that way. Labour is important because it needs to get done and I believe that without labour then it’s just concept. I was trained as a sculptor so I like process, I like labour, I like, you know, I liked carving wood, I like carving stone, I like stretching canvases, that was always as much a part of the work as whatever it was that you were doing. Visual artists are really into labour and I just took that whole ethos and applied it to writing, which was why I always loved concrete poetry because it had a material feel to it. I mean that Simon Morris documentary that he did was called Sculpting with Words, and I feel the same way still, about it, even though it’s book-based production. Take the Walter Benjamin project that I did, Capital, I mean [shouts] it’s a COOL IDEA, but it’s even cooler that I fucking took ten years to do that. It’s cool. It’s a great book. It’s a great idea but it’s a better book, and that’s the insanity, that’s the sort of insanity of the thing, to actually take the craziest thing you can possibly think of and do it.

Hotel

On Capital, I’d be fascinated to know about the actual construction process, because to me as I read some of the sections I felt as that there were very active organising principles at play. I would be interested to know how you actually went about organising material, collecting and collating material for that project.

K.G.

Well it was easy because I didn’t have to invent anything. I just took Benjamin’s idea of how to construct a book out of citation and took it literally and did it. I mean it was actually the easiest thing in the world. It was like paint by numbers and then I just went to libraries—and it was all library based—and I pulled books off the shelf about New York and I’d say, ah, that looks interesting, and I’d take it and I’d…I really would just sort of open it up and just kind of flip through it and [softly] “Oh, look at that, that’s so beautiful.” And then I’d type it out and then later I’d file it under a convolute. The thing that I did and that you’d probably notice about the book if you’ve actually spent some time with it, is that it’s highly sequenced, and of course Benjamin’s book was just notes and they were in no specific order and it was montage but nobody knew if it was going to actually be a notes for a project or a project in itself, you know all the problems that we know about that book. I thought, look, I’m going to do this, and I’m going to sequence it, really precisely, which sometimes meant changing tenses, in the things that I found, um, which sometimes meant, illuminating chunks of a citation without telling anyone, just taking a very large chunk and then cutting out half of it or this sentence here or this sentence there because it had to kind of go with the one around it. I remember somebody, maybe it was in The TLS discovered that I had tampered with the evidence, which, you know, why not? And it was such a mess anyway, you know, you work on something for ten years, I can’t remember what I did to what and you know I really wanted to ultimately publish the book without citation, but my publisher wouldn’t let me.

Hotel

But Verso made you?

K.G.

They made me put in citations and I said, well we’re going to put them in this tiniest font, and we’re going to put them on the gutter, and hopefully they’ll kind of disappear. I was having a conversation about this with John Zorn, the musician, with whom I’m collaborating, and John said, “Oh, well you know, if you had to work with me and—oh I’m sorry [KG accidentally touches Gert-Jan’s leg with his hand]—if you had to work with me what I would have done is printed all the citations in full in clear ink. I was like “ahh, that’s a brilliant idea.” And the other thing that was great about it was that it’s a thousand pages of citation I got no permission from anyone. I did not write to a single person. I just fucking did it. The book was as much about information management and copyright as it was about New York. I mean the content was easy, but that’s UbuWeb. The content on UbuWeb is easy, I mean honestly, put enough cool stuff together you’re going to get something really cool and big and just do it. But what Ubu really is about, is about distribution, free culture and copyright. And, the content of it is the easiest part and, it’s the same, identical thing in Capital. The exact same thing. Of course it’s easy to find good things, you know, I know I’m going to write a beautiful book, but I’m also going to do it, you know, without asking anyone, and, you know, having the most minimal form of citation possible. And nobody seemed to care—by the way. But nobody really seems to care about UbuWeb either. Twenty years of breaking the law, essentially, nobody, I mean a few people once in a while say something.

Hotel

Have there been problems with UbuWeb?

K.G.

Not really no. Once in a while an artist will say “take my stuff off there” or something like that, but nothing serious. And if something is removed from Ubu, somebody doesn’t want something, really doesn’t want something up there then I’ll take it down. And then you never even notice that it’s gone, [laughter] because there’s so much stuff up there, it would be really hard to decimate that archive. So anyway that’s where the notion of the archive and my work. Capital is an archival work, it’s a subjective work, but so is Ubu. Ubu pretends to be a vast, knowledgeable resource of something when in fact it’s bullshit, it’s false, I…I’m just a poet, I don’t know anything about what I’m doing, but because it’s been around for so long and I’ve been breaking copyright for so long and it’s the only thing out there, it’s become an institution, but I’m not the right person to be doing that. And that was the same thing with Walter Benjamin, of course I’m not Walter Benjamin, I mean come on man, and that’s why I made it gold, like I didn’t want you to think that this was trying to be some deep, Benjaminian thing. I just took a process from Benjamin, I admire his eye, he picked really good stuff for The Arcades Project, in fact it’s really, everything he picked was great, and I thought wow, maybe I could pick some good stuff too, and that was it. I was really just using somebody else’s concept. But it took a long time and it was very very different, those two books couldn’t be more different from each other, Benjamin and my book. It was fun. I loved doing that book. I loved it. I was so sad when it was over. I was really sad. Well, the thing is, I thought I’d never publish that in my life. I was convinced that first of all because of the copyright issues, second of all because of the length that I would go to my grave, with it being my great unpublished work. I would have been okay with that, but then Verso approached me and they said, “We’ve heard about this book.” I said, “Oh yeah?” and lo and behold, they wanted to do it and they came through. They’re, they’re wonderful, that’s a great press.

Rekto:Verso

I have a question about open access copyright. You are in favour of open access and in Wasting time on the internet you mention incidents in which work from JSTOR and other academic work is made publically available. I was wondering what you think about creative workers’ products because academics are often employed by universities and do not necessarily have their income based on the [profits from] their publications, but that differs in creative work, so, I was wondering how you..

K.G.

[interrupts]

Yeah, it differs in that in creative work you get paid nothing as opposed to maybe you get paid something in academic work. I mean the margins on this are very low. Any time UbuWeb bumps up against something that’s financially lucrative we get in trouble because people want to sell it, and there’s a market, and I don’t begrudge them that. Unfortunately most of what is on UbuWeb nobody wants to buy and if you tried to sell it you’d lose a lot of money. Not all of it, but most of it. I know a million people that have tried to put out avant-garde CD labels, and they produce beautiful things and god bless them, but they usually end up going broke, because the audience is too small. So you have somebody like La Mont Young who makes records for, you know, a hundred and fifty dollars that nobody can afford and I’ve actually said to him, you know you’re denying your work to people that really want your work and most people that like your work don’t have a lot of money because they’re into weird stuff? I mean [laughs] people can’t spend that kind of money on that and, you’re being an elitist, and you’re playing to people that have money and that’s not right, and that’s why people keep bootlegging his records and he can’t really do anything about it because how are you going to stop bootleggers? when people really want something.... I also think that if you’re an artist, and you’re bootlegged, you fucking made it. I mean how many artists don’t want to get bootlegged? I mean how many writers? Nobody would even bother bootlegging their work, like that’s such a big compliment, somebody wants to pirate my work, I’m like [silly high pitched voice] yes, and it happens to me all the time because I’m always the person that says pirate-it-pirate-it, and every time it happens I’m like great, because I don’t make any money from those books, that’s why I have an academic job. So it’s fine, for a certain set of cultural artifacts, but there are another set of cultural artifacts that have a very robust economy around them and I actually think that, as a free copyright person, I think they have every right to protect those properties. It’s a different game. I don’t begrudge them that... if I owned a property that was worth millions of dollars I probably would spend money to protect it too, but for what I deal with that really isn’t the case and most of the time what I’ve found, even on, say, Ubu, is that when people have their work up they tend to be looked at, they tend not to be forgotten, they tend to have paid opportunities to speak, they’re being talked about, they’re being written about. At this point, for a certain set of cultural artifacts, if it’s not on Ubu it’s going to be really hard to get too much interest going. So I don’t think it’s a one blanket rule, I don’t like this idea of copy-left and copy-right, I actually think it’s a very very complicated mix and you have to know what set of morals and distribution your artefact happens to fit in to, what schema it is. I think we need to be realistic about that. No sound poetry is ever going to win a grammy, you know, but no grammy is going to be kind of traded on places like Ubu. They’re not going to have intellectual cred. There’s so many types of cred to have out there, and Ubu has kind of just managed to figure out that balance, hit that that sweet spot. It was a hard thing to figure out, but now I kind of get it.Hotel

That’s interesting in itself because one of the things that the Internet facilitates very easily is change. I mean if you collected Ubu web in a physical archive and you took somebody’s work and you put it into a library it would be there and unless you went in and burnt it that would take some effort to take someone‘s work out of that whereas with UbuWeb if someone‘s work is online and they say oh actually you know I’d rather not be on there, you can just take it down. I feel like the internet allows for these decisions to be perhaps less meaningful because internet content can be changed...

K.G.

[interrupts]

It’s both. Like I was saying about the books it’s both. I mean sometimes you go to the library, sometimes you use it on Ubu. I wish everything was online so I didn’t have to leave my office, but sometimes it’s not and I need something deeper and, thank god, there’s the library and you know look [picks up a magazine] this is exactly what I was talking about, journals never looked like this. [laughs] They were never this beautiful. The beauty of this book is the result of the internet, it’s funny.

Hotel

I thought when you were speaking about that earlier it was very prescient when you said the web has given us back the artefact...K.G.

It’s true! Look how…look at this [picks up the magazine again]. I mean it’s like a minimalist painting, with the flesh and the pink, it’s absolutely exquisite, if you had given me this in the early 90s it would not have looked like this.

Hotel

Maybe just lastly on the subject of UbuWeb and Capital, they both have a concern, I think, for history in the sense that they are trying to collect a tradition that perhaps might be lost and notions of archiving are, I think, crucial to that. I was wondering what you understand by the term archive?

K.G.

Well, in Wasting time on the Internet, there’s a chapter called “archiving as the new folk art” and that comes from the alt-librarian Rick Prelinger of the Prelinger archive. Rick’s idea is that the way we archive is the way people use to knit or make quilts, like unconsciously gathering and putting back together, making sense of small shards, such as say quilting, with little bits of fabric that create something very beautiful and very personal. But you did not make that fabric. In the same way, my mp3 archive is a personal expression of myself, it’s sort of a work of folk art, the way I have it organised and what’s in there is a deep expression of who I am, and who I am is inconsistent and strange and riddled with guilty pleasures. You would think that all I would have there would be avant garde but in fact there’s plenty of dumb pop music smuggled in. I just think like the contemporary archive is an eclectic archive, it’s an impure archive; impurity is the distinction between a folksonomy and something official, and UbuWeb is that way too. It’s got a lot of weird shit in there that wouldn’t usually sit together. On UbuWeb there’s Samuel Beckett - B-E-C-K - next to Captain Beefheart - B-E-E-F - and you never see those works together Captain Beefheart and Samuel Beckett, but if you think about it… err… the figure of Captain Beefheart in the 1960s could not have been done without the figure of Samuel Beckett, and yet nobody would ever think to put those two together, although I would assume that most lovers of Beefheart are lovers of Beckett, I’m not so sure it goes the other way around, but for those of us for whom it goes both ways that would be the weirdness of the UbuWeb archive. The Beckhettians, of course, are too pure - all that junky pop music, 60s psychedelia, you know - but no, we could actually kind of make those connections. So the intuitiveness of Ubu is expressed by those two names. I don’t know why, there’s no book that tells me that they should go together, that they can hang out together, but… it kind of works, you know, and that’s it, and it’s very impure and I’m interested in impurity at this point… and that’s why with UbuWeb I can actually use the term “avant-garde” because, really, it’s not the old avant-garde art, which was modernism, which was very pure. I mean it’s a total staining and soiling of that purity that I’m interested in, and I think that the contemporary archive is the impurity, it is the impure impulse and being okay with that…Wow…that’s interesting…that works. It works for all of us, isn’t that honest?

Rekto:Verso

You said that you like the fact that people copy your own work, I was also wondering to which degree you see your own works as manuals?

K.G.

Yeah, they are manuals, but very few people take me up on that. There was one instance. I did a book called Traffic, which was traffic reports over the course of 24 hours, and finally these poets in São Paulo did that book for São Paulo traffic. I thought that was great, and they published a little book of it, and I thought that’s the only instance of it I can think of. It’s so easy, but people don’t do that. I don’t know why. Maybe they think it would be imitative, but I think it would be very different, you know, so, I’m good with that.Rekto:Verso

And what do you think that people could gain by appropriating your methods? Or using your ideas?K.G.

I don’t know. What did I gain by appropriating Walter Benjamin’s methods? Like: a lot. That was the same thing, I just looked at Benjamin as a manual... here’s how I can write a cool book about New York, that’s all. And, yeah, it worked out really well, it’s good, you know, I think we should use each other’s concepts because no matter what we do it’s bound to be different.Hotel

What about that idea of the manual in relation to creative writing and how that has increasingly been taught, certainly in the Anglophone world, in relation to certain formulas such as some people see in say a New Yorker short story...K.G.

[interrupts]

Yeah, it’s equally formulaic, but they don’t like to admit it. Hollywood movies, a New Yorker short story, I just wish they would admit it, you know, but they don’t. It all has to be original. It’s a fallacy of creativity. It’s not creative at all, it’s a fallacy, whereas I’m saying actually, you know, you’re as formulaic as I am. I mean with sonnet writing is a formula, it’s Oulipian, you have to follow these certain forms and then it’s paint by numbers really, so what’s wrong with that? Does anybody have a problem with the sonnet? Because even if you do somebody else’s thing again it turns out to be new and it turns out to be different, it turns out to be original, just like I was saying in the lecture, even if two people transcribe the same thing, even the difference of a period or a colon, you know, or a semi-colon, is going to make an entirely different text. In Jewish tradition, with the copying of sacred texts, if it’s off by one typo the whole text is destroyed. That’s so interesting to me, they think of the typo as destructive, I think of it as a version. Religion can’t do versions, they have to destroy the text if there’s one typo found, the whole thing has to be tossed out and re-done again. I happen to have a more generous point of view, but I get it, I, you know, I get it. One of the things that we do with the students is we go in and edit Wikipedia pages but not by changing the content but by changing like a comma to a semi-colon and that change registers in the history as much as if you deleted a paragraph, which is really cool. We vandalise Wikipedia pages by going in and changing like an “a-n” to an “a.” [laughs] You know, it’s just that kind of weird shit, like go in and vandalise a Wikipedia page to the point where it would be invisible and then why would anybody even both correcting that? I mean it doesn’t register, it registers profoundly, but it doesn’t register at all. This is interesting to me. It’s like microsound. Do you remember that whole movement, maybe it was in the 90s, of sounds that were almost inaudible - like almost like dog whistles - and that were used as an aesthetic. What about micro expression, micro-writing, I think that's really, really beautiful, like just altering things very subtly in that way, I’m interested in that. Changes of the world. I mean it’s Duchampian. The world is different because this thing now moved from here to here [moves the phone that is recording the interview on top of the magazine]. I could write a book on the difference between what that means here and what that means here [moves the phone back and forth from on top of the magazine to off the magazine]. I mean, come on, that was Duchamp already: it’s already very old, this kind of idea.

Hotel

But do you feel that literature has a resistance to that playfulness?K.G.

They’ve never even thought of it. I’ve had people tell me that that’s not literature, that’s not writing that’s typing, that means nothing, what are you talking about? Give me some meaning. I’m like, but isn’t there so much meaning sitting on this table? [refers again to the phone and the magazine] Are you stupid? You’re supposed to be a writer, are you stupid that you cannot see the meaning, not only in when this is moved, but even the meaning of this as an object? I mean how is it that artists can’t see that? I think they’re fucking crazy. They’re stuck. They’re stuck on something and I think it’s insensitive. I think it’s naïve and I think it’s insensitive and I think it’s romantic and I think it’s heroic, and I think it’s all the things that art isn’t or shouldn’t be in that way.

Rekto:Verso

Maybe a question on affect.

I have the impression that, when reading Wasting time on the Internet, that affect is very important to you.

K.G.

Yeah, loving that, loving it.

Rekto:Verso

I was wondering if you could say something about affect?

I love it. I’m interested in telepathy and affect in the digital space. I’m feeling that we’re constantly intuiting and anticipating the interval, the space between things. The web doesn’t happen in real time. There’s always an interval, and that interval is pregnant, and that interval is an affect factory. So when we’re texting each other and I text you something and I see those three dots, you know that says that you are typing, I mean whoever invented that one is like [exclaims] wow [laughs] you know, that is so emotional. That’s so affective, and I think social networking is affective. We’re in the situation where we’re speaking not just to one person or to two people but we’re speaking to, you know, hundreds of thousands of people at once and then how do you predict how that’s going to be received? How do you write something that’s going to be read and understood by say the UbuWeb twitter feed which is like 85,000 people—of course most of them are robots and then nobody’s paying attention—but even if it’s 4,000 that happens to be looking or 2,000, this is unprecedented. It’s an unprecedented situation in the history of the world, you have to really think about how is this going to be received, and there’s going to be a lot of um misunderstanding. When you’re speaking to that many people, you’re going to misunderstand. So the affect is anticipation and prediction and telepathy. If it’s one on one you can really get it, I’m trying to reach your mind, you know, but it can happen both on the vast scale of social media and on the intimate scale. If I send a job resume out, my affectual state, you know, it’s pre-emotion, it’s not emotion, it’s the sweaty palm. And when I send the job resume out on the web, my palm is sweating, you don’t see me sweating but my heart is palpitating and it’s bodily, it’s physical, the web induces physical changes within us, and then the guy on the receiving end is probably in an affectual state as well, but when I get that response back that yes I got the job, or no I didn’t, then that affect has gone and it converts to emotion. So what do I do with that emotion? I’d probably then send a text to my wife saying [raises voice] fucking hell I got the job man, you know, but then I’m waiting for her affectual response back to my enthusiasm, like Oh, I got this job, how’s that going to affect are family. Yeah, I’m thinking a lot about that, and I’m thinking about the occult a lot as well. The whole web feels like a Ouija board you know with automatic writing and the stuff we’re talking about with surrealism.1 All of that stuff is really driving the web, with a mixture of irrationality and rationality. I’m fascinated by the grid, that holds the whole thing together, and then the organic flesh and emotion that’s hung upon that grid, which is a fucking mess, and it’s dripping, but it’s held in place by a grid and it’s always the two, between the organic and the architectural, that is giving it a lot of zing, because if it was just architecture the way computers used to be you’d be like “ah, that’s just a machine,” and if it’s all just like an emotion, then it’s something else, but it’s a combination of the two, the infrastructure of something like social media, the programming, the complex programming between Twitter that allows affect and emotion to thrive. So yeah, I’m very interested in this now. I’m thinking a lot about it. I’m feeling it.Rekto:Verso

In your book you often describe projects in terms of whether they are interesting or not, successful or not, and I always have the impression that affect or emotion is very important in enabling you to make those kind of judgements...K.G.

Can you be a little bit more specific?

Rekto:Verso

You describe how when you started the course Wasting time on the Internet, that the course wasn’t very successful to start with and I was then wondering what doesn’t make it successful? is that people aren’t really engaged, aren’t really driven on an emotional level?K.G.

It’s also bodily. People say we have no bodies anymore, well that’s just ridiculous. That class works because we’re all in the room together. Otherwise that would just be reifying the distance that happens online, but in those classrooms, the devices become amplifiers of emotion and affect, instead of prohibiting emotion and affect. It’s very very strong, but we never do it, we mostly waste time on the internet on our own in a Starbucks or a library and everybody’s sitting there and there’s just nothing going on. Something’s happening out there but not in the room, but here we all are in a room together and crazy, wonderful things do happen there as a result. It’s really interesting.

Hotel

One of the things that struck me when reading your descriptions of the classes you taught on Wasting time on the Internet, was the exercise where the students pass the laptops around in a circle and they can explore each other’s files and folders and you describe a situation where complete fear actually becomes something quite close to relief, and it became an almost therapeutic exercise. But for a lot of people the internet has had a very negative impact on people’s mental health and is sometimes seen as this very isolated pursuit of ephemeral pleasures that have no relation to the real world. What are your thoughts on the relation between the internet and well-being?K.G.

I mean, look, that’s like asking the relationship between alcohol and well-being. Most people use alcohol okay, some people don’t, some people have problems with alcohol, they’re alcoholics, but most people, the great majority, handle alcohol quite well. I think that the morality comes from the application of older media onto newer, that like a TV generation are putting their shit that they got when they were a kid onto their kids that are watching the internet. It’s different, but it’s okay. It’s gonna be okay, because I was told when I was a kid that it wasn’t going to be okay, that my mind was rotting, I was a couch potato, all of those terrible warnings but what happened to me was that I had so much TV when I was a kid that I kind of got really bored of it, and I stopped looking at TV, probably some time in high school. I mean it didn’t turn out to be that way, but for some people it was a problem, some people just sat there and consumed vast amounts of TV. I don’t know, I feel very positive. I feel like it’s going to be okay. It’s going to be different. My kids aren’t great book readers, and that makes me sad as a big book reader. I’m like oh, don’t you want to read, and then I have to think about it and I’m like but if I had this would I be reading? Why would I be reading? That’s a 19th century pursuit that was handed down to me from on high. I look at what they’re looking on the web and it’s mostly educational. My seventeen year old yesterday was looking at something and I said why are you looking at infrastructural projects in Saudi Arabia, a video that’s a documentary about infrastructural projects in Saudi Arabia? I’m like why are you looking at that? Would I have ever read a book about that? No. But it’s something he’s stumbled on and was done in a compelling visual way that told a story and made him smarter. So in a way he’s better than me because he’s not just wasting time on the internet, he is doing that too, but it’s not just that. I mean the web isn’t just wasting time. What about the Wikipedia phenomenon? Who doesn’t dive into Wikipedia? What’s wrong with that? When I was a little kid I loved opening up the encyclopaedia and flipping through. I mean I don’t see it happening in the bad way that everyone’s saying it is. I know for some people it is in a bad way but I think for most it really isn’t. I think it’s a lot of fear and I think, you know, I just think people have to get over it, because it’s not going away. Enough already let’s make peace with it, but man this is a hard one for a lot of people. But you know why, because it’s so good, it’s so compelling, it’s so fascinating, there’s so much interesting stuff, you can follow your passions. It’s not like TV where, when I was a kid there were five channels, and it was mostly down throwing crap at me, nothing was there…it’s all good.

It’s going to be okay.

A Note

1. Always keen to name twentieth century soothsayers for the twenty-first century moment, Goldsmith regularly cites the significance of Surrealist thought to our analysis of the internet both at a technological level and in his more practical perambulations on the habits of the active-user. Writing in The New Yorker, in a piece entitled ‘Why I am Teaching a Course Called Wasting Time on the Internet,' Goldsmith introduces his position by historicising the internet in terms of a foundational understanding of surrealism-as-movement:

“The Surrealists’ ideal state for making art was the twilight between wakefulness and sleep, when they would dredge up images from the murky subconscious and throw them onto the page or canvas. Proposing sleepwalking as an optimal widespread societal condition, André Breton once asked, “When will we have sleeping logicians, sleeping philosophers?” It seems that the Surrealist vision of a dream culture has been fully realized in today’s technologies. We are awash in a new, electronic collective unconscious; strapped to several devices, we’re half awake, half asleep. We speak on the phone while surfing the Web, partially hearing what’s being said to us while simultaneously answering e-mails and checking status updates. We’ve become very good at being distracted. From a creative point of view, this is reason to celebrate. The vast amount of the Web’s language is perfect raw material for literature. Disjunctive, compressed, decontextualized, and, most important, cut-and-pastable, it’s easily reassembled into works of art.”

‘Why I am Teaching a Course Called Wasting Time on the Internet,' The New Yorker (November 13th, 2014)

* * *

The influence of Dadaism on contemporary thought and feeling also does not go unmentioned in his commentary. Prefacing an exhibition of the work of Francis Picabia (b.1879; d.1953) at The Museum of Modern Art, New York [Francis Picabia: Our Heads Are Round so Our Thoughts Can Change Direction], Goldsmith talks to The Art Newspaper about Picabia’s clairvoyance:

“There is no one iconic image that stands for Picabia in the way that, say, water lilies do for Monet or soup cans do for Warhol. By comparison, Picabia’s oeuvre is an ongoing series of purposely “weak” images that dance around Modernism’s strong points in order to undermine them. But from a 21st-century digital perspective, the “poor” image—as critics like Hito Steyerl and Boris Groys have suggested—is an effective way of critiquing power structures. Picabia, it seems, predicted the way images would be circulated and consumed in the digital age. The timing of the show is perfect: in Dada’s centenary year, America elected a latter-day Ubu Roi for president. The Dada dictator first imagined by Alfred Jarry in his 1896 play of the same name is a narcissistic kleptocrat who impetuously invades various countries, swears like a sailor and sets about robbing his populace blind. He specialises in disinformation and is the early Modernist embodiment of “post-truth.” You can almost hear Picabia on the sidelines giggling with delight, saying: “See? I told you so.”

— See ‘Wrong in the right way: Kenneth Goldsmith on why Picabia’s false Modernism feels so True,’ The Art Newspaper [February 3rd, 2017]

1. Always keen to name twentieth century soothsayers for the twenty-first century moment, Goldsmith regularly cites the significance of Surrealist thought to our analysis of the internet both at a technological level and in his more practical perambulations on the habits of the active-user. Writing in The New Yorker, in a piece entitled ‘Why I am Teaching a Course Called Wasting Time on the Internet,' Goldsmith introduces his position by historicising the internet in terms of a foundational understanding of surrealism-as-movement:

“The Surrealists’ ideal state for making art was the twilight between wakefulness and sleep, when they would dredge up images from the murky subconscious and throw them onto the page or canvas. Proposing sleepwalking as an optimal widespread societal condition, André Breton once asked, “When will we have sleeping logicians, sleeping philosophers?” It seems that the Surrealist vision of a dream culture has been fully realized in today’s technologies. We are awash in a new, electronic collective unconscious; strapped to several devices, we’re half awake, half asleep. We speak on the phone while surfing the Web, partially hearing what’s being said to us while simultaneously answering e-mails and checking status updates. We’ve become very good at being distracted. From a creative point of view, this is reason to celebrate. The vast amount of the Web’s language is perfect raw material for literature. Disjunctive, compressed, decontextualized, and, most important, cut-and-pastable, it’s easily reassembled into works of art.”

‘Why I am Teaching a Course Called Wasting Time on the Internet,' The New Yorker (November 13th, 2014)

* * *

The influence of Dadaism on contemporary thought and feeling also does not go unmentioned in his commentary. Prefacing an exhibition of the work of Francis Picabia (b.1879; d.1953) at The Museum of Modern Art, New York [Francis Picabia: Our Heads Are Round so Our Thoughts Can Change Direction], Goldsmith talks to The Art Newspaper about Picabia’s clairvoyance:

“There is no one iconic image that stands for Picabia in the way that, say, water lilies do for Monet or soup cans do for Warhol. By comparison, Picabia’s oeuvre is an ongoing series of purposely “weak” images that dance around Modernism’s strong points in order to undermine them. But from a 21st-century digital perspective, the “poor” image—as critics like Hito Steyerl and Boris Groys have suggested—is an effective way of critiquing power structures. Picabia, it seems, predicted the way images would be circulated and consumed in the digital age. The timing of the show is perfect: in Dada’s centenary year, America elected a latter-day Ubu Roi for president. The Dada dictator first imagined by Alfred Jarry in his 1896 play of the same name is a narcissistic kleptocrat who impetuously invades various countries, swears like a sailor and sets about robbing his populace blind. He specialises in disinformation and is the early Modernist embodiment of “post-truth.” You can almost hear Picabia on the sidelines giggling with delight, saying: “See? I told you so.”

— See ‘Wrong in the right way: Kenneth Goldsmith on why Picabia’s false Modernism feels so True,’ The Art Newspaper [February 3rd, 2017]

Hotel is grateful to Arne DeWinde; and to Gert-Jan Meyntjens for a fruitful collaboration.

Photographs of the The PXL-MAD Lectures are the work of Boris Van den Eynden.