RAISE, or HOW TO BREAK

FREE OF THE GROUND,

or THE LAKELAND DIALECT

FOR ‘SLIPPERY’ IS ‘SLAPE’

& TO FORM IT IN THE MOUTH

REQUIRES AN ACT OF FALLING

Katie HALE

shortlisted for the DESPERATE LITERATURE

short fiction prize, 2021

short fiction prize, 2021

A pamphlet collating stories from this year’s shortlist (as juried by judges Otessa MOSHFEGH, Deerek OWUSU, & Isabel WAIDNER) can be found here, & see below for Katie HALE’s entry— ‘RAISE, or HOW TO BREAK FREE OF THE GROUND, or THE LAKELAND DIALECT FOR ‘SLIPPERY’ IS ‘SLAPE’ & TO FORM IT IN THE MOUTH REQUIRES AN ACT OF FALLING’—a shortlisted story commended by the judges & awarded a residency at THE WRITERS’ HOUSE OF GEORGIA (მწერალთა სახლი), Tbilisi.

Begin at yon coffin stone: flat-topped boulder at the foot of the fell, positioned for resting the burden of the dead. Your hand is small but your brother’s smaller. It twitches in yours, a caught insect, and when he grins at you, you roll your ten-year-old eyes, keep on climbing for the beck. You drag the plastic net behind you.

No. Stop. Let me begin again.

Up aback of yon coffin stone, your brother’s hand in yours a caught insect, a metal bucket in his other. When you offer to take it, he tells you, ‘No way, José’, even though really it’s too big for him, even though the path is steep and difficult, even though the rocks are stern. Sometimes it clangs against the ground. Sometimes he kicks it accidentally and stumbles, but he always pulls himself back up, barrels out his chest like the bodybuilders on telly.

He’s going to fill the bucket from the tarn at the top of the fell. He’s gonna catch a flickering silver fish, he says: a tiddler he can scoop in his insect hand, let it wriggle in his palm, go still. Then, he says, he’ll put it back. After all, he’s not a monster, just a small kind of god.

The sky out over the lake is a centrefold, a glossy falling open after rain. You climb to where the path becomes trickle, becomes syke, becomes beck. This happens sometimes: boots and water pulled by the same gravity. The rocks are slick with moss.

Your brother has tramped the bottom of the dell till his trainers are clarty with mud. He stomps through the water, saying, ‘Jeez, it’s cold.’ When you ignore him, he stamps harder and says, ‘I said, jeez, it’s cold.’ His soles are worn from where he’s scuffed them along the pavement, and his laces trail like unfinished sentences. It’s the summer holidays before you turn eleven, before your last year at the little village school, and you’re almost an adult in your fake suede jacket, your purple dungarees—

Again.

It’s the summer holidays before you turn eleven, and you’re almost an adult in your fake suede jacket, your purple dungarees. Your mam has said, ‘Look after your brother,’ and, ‘Make sure you’re back by lunch.’

So you begin out past Town End aback of the dead poet’s cottage. Past the car park, the coaches, the disgorged tourists here for long-wilted daffodils and a clutch of gingerbread from the famous shop. Past yon coffin stone with its box-flat top, where two collies beg as a woman tucks into her bait, as she ignores you and your brother and the dogs.

Happen your grip is a gin trap, and your brother keeps twining on about the climb. ‘Let us rest a mo—go on.’

Somewhere in the deciduous garden of Wishing Gate House, a squirrel taps hazelnuts against its teeth—a scrape, a patter, a tum- ble of shells between branches. A clutch of sparrows. Thrum of wings. From the opposite fell, a white flock of birds merges with the sky: inconsequential gods departing a dead religion. Out on the lake, an old man rows the disturbed creases of the water, and a skein of geese skitters in to land.

‘Stop twining and move.’ You pull your brother up to where the path becomes trickle, becomes syke, becomes beck, metal bucket a clang against the rock.

Metal bucket a clang against the rock, you walk out through Town End, past the sheep skull nailed to the lintel, up, aback of the dead poet’s cottage. Yesterday’s rain furrows the edges of the track, gathers leaf mulch in the gutters. The mizzle is a spider’s web clinging to your face. Already your calves are heavy, your breath a helicopter whirring across the valley.

Look after your brother. Make sure you’re back by lunch. Up the curling border of the dell—fringe of kingcup, thunder flowers with rainstorms locked inside—happen your brother starts twining on about the climb. ‘Let us rest a mo—go on.’

But it’s the summer holidays before you turn eleven. You’re almost an adult in your fake suede jacket, your purple dungarees, and your mam has said, ‘Make sure you’re back by lunch.’

So you tell him, ‘We’ve not got time. Come on.’

Your hand is a gin trap. You drag him up to where the trail begins to tack, a zigzag of tumbled rock, which your brother calls, ‘Tougher’n climbing to heaven.’ He must have picked this up from school, because you’ve never heard it from your mam, and anyway it’s childish, thinking heaven is somewhere like a mountain you can climb to.

Once, your teacher asked: ‘If you build a ship and sail her across an ocean in the middle of a storm— then, when you arrive, swap out the oars for new ones—then, when the hull begins to rot, replace the boards—then, when the sails are blown to tatters, stitch up another set from different cloth—then, when the rigging can’t hold you up, buy a bunch of rope and knot yourself some more—and so on, and so on, till you’ve substituted every part—is she still the same ship that crossed the ocean in the storm?’

‘Yes, cos she’s still got the same name.’

‘No, cos there’s nowt of her old self left.’

Your teacher told you, ‘That’s the point—you get to decide what you mean by same.’

Past yon coffin stone—flat-topped boulder at the bottom of the raise, aback of the dead poet’s cottage—past the duck pond with its watchful heron, its fringe of thunder flowers and kingcup, happen you climb the curling border of the dell. Rain dashes you, the weight of a hefted flock. At the driveway for Wishing Gate House, your brother begs again to hear about the boggles and their hauntings. So you tell him he’s ladgeful. ‘Everyone knows they’re only stories.’

His hand twitches in yours, a caught insect, and mizzle like a spider’s web snags at your face. The gate is looped with bindingtwine, your fingers too cold, too wet to untie it. Happen in this tell- ing, you struggle with the knot. Happen the sneck is rusted shut, the gate a sudden ending, so you run home in your fake suede jacket, your purple dungarees—your brother’s trainers clarty, scuffed and slape. Your mam has said, ‘Make sure you’re back by lunch.’ And so, happen in this telling, you are.

Out past Town End aback of the dead poet’s cottage, you climb to where the path becomes syke, becomes beck, becomes force—becomes fierce white hurry that rushes the clart from your treads. The water tugs at your skin, unzips you like a boot.

Happen you remember that saying: how you can’t step in the same river twice. Happen you tell it to your brother, who calls you ladgeful.

The water dodges and slips—happen it weaves between your bones, so from your toes, you can feel your flesh unknitting, becoming flood. Next, your soles. Your ankles. Legs. Happen your brother’s hand twitches in yours, a caught insect, and when you fall—him first, pulling you after—both of you fall without breaking: liquid dance down the fellside; tumbling ghyll; water remaking itself as wish. Happen when you fall, you fall for something beautiful and calm, for the mirrored oblivion of the lake.

Again.

Past the duck pond with its watchful heron, loose change of kingcup at the fringe. Up the curling border of the dell.

Your mam has said the dell was dug out years ago, to unearth the bones for Wishing Gate House, which everyone knows is a rattled haunting, a cluster of boggles and ghouls. It hunkers between the trees, between the fleeting deer, the dead still playing out their stories on repeat.

Your mam has said, ‘Look after your brother,’ so happen when your brother stumbles, you’re the one who falls. Your head against a rock. Your eke of blood. You spreading, leaking your own red tarn across the path.

Your brother clangs the metal bucket, you drag him after.

Your brother’s trainers worn and clarty.

The rocks are treacherous and slape, boots and water pulled by the same gravity.

Your brother was a full pail of water, and you spill it: you’ve been telling this story your whole life.

Past the coffin stone, aback of the dead poet’s cottage, up the curling border of the dell. As you climb the path to Alcock Tarn, your brother’s hand is a caught insect, the mizzle a web on your face. Happen his hand grows stronger. Grip a gin trap. Dusting of dark hairs at the wrist.

Up through deciduous woods, squirrels flash the branches with red. Unloop the binder twine, unsneck the gate. Happen your brother is taller now, an Adam’s apple riding his throat, his chin bearded with the wild. When he smiles at you, little sister, your small hand twitches in his.

You have been telling this story your whole life—how, when the trail begins to tack, you will say, ‘Breather?’ but your brothershakes his chiselled head, and the first silver flutters from his hair like a blown cobweb.

His breath will become a helicopter whirring across the valley.

By the time you reach the open summit, happen Alcock Tarn will lie still and gleaming as a promise, and your brother stoop, his skin a tumbled crag. His feet are bare. He has lost the metal bucket. When he smiles (when he smiles at you, little sister), it’s a god ray splitting the clouds after rain. When he walks, shuffles, out into the tarn, he is a full pail of water, emptying himself back into the flood.

They say yon coffin stone is flat for the resting of burdens, flat from the repeated weight of the dead.

At school, you learned how the universe is infinite, and also still expanding, and how somehow both these things can be true.

Happen you perch a moment on yon coffin stone, to decide what you mean by true. You have been telling this story your whole life, and now, when you gather your words, they flicker, fish circling a metal bucket, waiting for you to return them to the tarn.

Catch your breath, the way you would snatch a tiddler from the beck, the way you would catch a hand to stop it falling.

The path is always there, aback of the dead poet’s cottage, curling up the border of the dell. When you stand, send the roe deer askitter between the trees, the heron panicking away towards the lake. Up at the house, the boggles will continue their relentless haunting.

The path is always there. And so now, begin.

/

No. Stop. Let me begin again.

/

Up aback of yon coffin stone, your brother’s hand in yours a caught insect, a metal bucket in his other. When you offer to take it, he tells you, ‘No way, José’, even though really it’s too big for him, even though the path is steep and difficult, even though the rocks are stern. Sometimes it clangs against the ground. Sometimes he kicks it accidentally and stumbles, but he always pulls himself back up, barrels out his chest like the bodybuilders on telly.

He’s going to fill the bucket from the tarn at the top of the fell. He’s gonna catch a flickering silver fish, he says: a tiddler he can scoop in his insect hand, let it wriggle in his palm, go still. Then, he says, he’ll put it back. After all, he’s not a monster, just a small kind of god.

The sky out over the lake is a centrefold, a glossy falling open after rain. You climb to where the path becomes trickle, becomes syke, becomes beck. This happens sometimes: boots and water pulled by the same gravity. The rocks are slick with moss.

Your brother has tramped the bottom of the dell till his trainers are clarty with mud. He stomps through the water, saying, ‘Jeez, it’s cold.’ When you ignore him, he stamps harder and says, ‘I said, jeez, it’s cold.’ His soles are worn from where he’s scuffed them along the pavement, and his laces trail like unfinished sentences. It’s the summer holidays before you turn eleven, before your last year at the little village school, and you’re almost an adult in your fake suede jacket, your purple dungarees—

/

Again.

/

It’s the summer holidays before you turn eleven, and you’re almost an adult in your fake suede jacket, your purple dungarees. Your mam has said, ‘Look after your brother,’ and, ‘Make sure you’re back by lunch.’

So you begin out past Town End aback of the dead poet’s cottage. Past the car park, the coaches, the disgorged tourists here for long-wilted daffodils and a clutch of gingerbread from the famous shop. Past yon coffin stone with its box-flat top, where two collies beg as a woman tucks into her bait, as she ignores you and your brother and the dogs.

Happen your grip is a gin trap, and your brother keeps twining on about the climb. ‘Let us rest a mo—go on.’

Somewhere in the deciduous garden of Wishing Gate House, a squirrel taps hazelnuts against its teeth—a scrape, a patter, a tum- ble of shells between branches. A clutch of sparrows. Thrum of wings. From the opposite fell, a white flock of birds merges with the sky: inconsequential gods departing a dead religion. Out on the lake, an old man rows the disturbed creases of the water, and a skein of geese skitters in to land.

‘Stop twining and move.’ You pull your brother up to where the path becomes trickle, becomes syke, becomes beck, metal bucket a clang against the rock.

/

Metal bucket a clang against the rock, you walk out through Town End, past the sheep skull nailed to the lintel, up, aback of the dead poet’s cottage. Yesterday’s rain furrows the edges of the track, gathers leaf mulch in the gutters. The mizzle is a spider’s web clinging to your face. Already your calves are heavy, your breath a helicopter whirring across the valley.

Look after your brother. Make sure you’re back by lunch. Up the curling border of the dell—fringe of kingcup, thunder flowers with rainstorms locked inside—happen your brother starts twining on about the climb. ‘Let us rest a mo—go on.’

But it’s the summer holidays before you turn eleven. You’re almost an adult in your fake suede jacket, your purple dungarees, and your mam has said, ‘Make sure you’re back by lunch.’

So you tell him, ‘We’ve not got time. Come on.’

Your hand is a gin trap. You drag him up to where the trail begins to tack, a zigzag of tumbled rock, which your brother calls, ‘Tougher’n climbing to heaven.’ He must have picked this up from school, because you’ve never heard it from your mam, and anyway it’s childish, thinking heaven is somewhere like a mountain you can climb to.

/

Once, your teacher asked: ‘If you build a ship and sail her across an ocean in the middle of a storm— then, when you arrive, swap out the oars for new ones—then, when the hull begins to rot, replace the boards—then, when the sails are blown to tatters, stitch up another set from different cloth—then, when the rigging can’t hold you up, buy a bunch of rope and knot yourself some more—and so on, and so on, till you’ve substituted every part—is she still the same ship that crossed the ocean in the storm?’

‘Yes, cos she’s still got the same name.’

‘No, cos there’s nowt of her old self left.’

Your teacher told you, ‘That’s the point—you get to decide what you mean by same.’

/

Past yon coffin stone—flat-topped boulder at the bottom of the raise, aback of the dead poet’s cottage—past the duck pond with its watchful heron, its fringe of thunder flowers and kingcup, happen you climb the curling border of the dell. Rain dashes you, the weight of a hefted flock. At the driveway for Wishing Gate House, your brother begs again to hear about the boggles and their hauntings. So you tell him he’s ladgeful. ‘Everyone knows they’re only stories.’

His hand twitches in yours, a caught insect, and mizzle like a spider’s web snags at your face. The gate is looped with bindingtwine, your fingers too cold, too wet to untie it. Happen in this tell- ing, you struggle with the knot. Happen the sneck is rusted shut, the gate a sudden ending, so you run home in your fake suede jacket, your purple dungarees—your brother’s trainers clarty, scuffed and slape. Your mam has said, ‘Make sure you’re back by lunch.’ And so, happen in this telling, you are.

/

Out past Town End aback of the dead poet’s cottage, you climb to where the path becomes syke, becomes beck, becomes force—becomes fierce white hurry that rushes the clart from your treads. The water tugs at your skin, unzips you like a boot.

Happen you remember that saying: how you can’t step in the same river twice. Happen you tell it to your brother, who calls you ladgeful.

The water dodges and slips—happen it weaves between your bones, so from your toes, you can feel your flesh unknitting, becoming flood. Next, your soles. Your ankles. Legs. Happen your brother’s hand twitches in yours, a caught insect, and when you fall—him first, pulling you after—both of you fall without breaking: liquid dance down the fellside; tumbling ghyll; water remaking itself as wish. Happen when you fall, you fall for something beautiful and calm, for the mirrored oblivion of the lake.

/

Again.

/

Past the duck pond with its watchful heron, loose change of kingcup at the fringe. Up the curling border of the dell.

Your mam has said the dell was dug out years ago, to unearth the bones for Wishing Gate House, which everyone knows is a rattled haunting, a cluster of boggles and ghouls. It hunkers between the trees, between the fleeting deer, the dead still playing out their stories on repeat.

/

Your mam has said, ‘Look after your brother,’ so happen when your brother stumbles, you’re the one who falls. Your head against a rock. Your eke of blood. You spreading, leaking your own red tarn across the path.

/

Your brother clangs the metal bucket, you drag him after.

Your brother’s trainers worn and clarty.

The rocks are treacherous and slape, boots and water pulled by the same gravity.

/

Your brother was a full pail of water, and you spill it: you’ve been telling this story your whole life.

/

Past the coffin stone, aback of the dead poet’s cottage, up the curling border of the dell. As you climb the path to Alcock Tarn, your brother’s hand is a caught insect, the mizzle a web on your face. Happen his hand grows stronger. Grip a gin trap. Dusting of dark hairs at the wrist.

Up through deciduous woods, squirrels flash the branches with red. Unloop the binder twine, unsneck the gate. Happen your brother is taller now, an Adam’s apple riding his throat, his chin bearded with the wild. When he smiles at you, little sister, your small hand twitches in his.

You have been telling this story your whole life—how, when the trail begins to tack, you will say, ‘Breather?’ but your brothershakes his chiselled head, and the first silver flutters from his hair like a blown cobweb.

/

His breath will become a helicopter whirring across the valley.

By the time you reach the open summit, happen Alcock Tarn will lie still and gleaming as a promise, and your brother stoop, his skin a tumbled crag. His feet are bare. He has lost the metal bucket. When he smiles (when he smiles at you, little sister), it’s a god ray splitting the clouds after rain. When he walks, shuffles, out into the tarn, he is a full pail of water, emptying himself back into the flood.

/

They say yon coffin stone is flat for the resting of burdens, flat from the repeated weight of the dead.

At school, you learned how the universe is infinite, and also still expanding, and how somehow both these things can be true.

/

Happen you perch a moment on yon coffin stone, to decide what you mean by true. You have been telling this story your whole life, and now, when you gather your words, they flicker, fish circling a metal bucket, waiting for you to return them to the tarn.

Catch your breath, the way you would snatch a tiddler from the beck, the way you would catch a hand to stop it falling.

The path is always there, aback of the dead poet’s cottage, curling up the border of the dell. When you stand, send the roe deer askitter between the trees, the heron panicking away towards the lake. Up at the house, the boggles will continue their relentless haunting.

The path is always there. And so now, begin.

DESPERATE LITERATURE is an international bookshop in the heart of Madrid, founded in 2014. They sell books in English, French and Spanish, working to build a literary community around and through these literatures. They (normally) run weekly events with authors from around the world, and in 2019 hosted Spain’s first English language poetry festival. They first launched the DESPERATE LITERATURE SHORT FICTION PRIZE in 2017. The Prize is an international attempt to recognise writers of innovative and experimental short fiction, with the aim of providing opportunities to all those shortlisted through a publishing and events programme that partners with literary organisations across Europe.

The 2021 edition was judged by authors Otessa MOSHFEGH, Deerek OWUSU, and Isabel WAIDNER.

A pamphlet collating all shortlisted stories, published by Desperate Literature, can get got HERE as a PDF (and a print copy, preordered).

With thanks to Terry CRAVEN and the prize team, Layla BENITEZ-JAMES, Dom CZAPLA, Charlotte DELATTRE, Robert GREER, Kate McCULLY and Emily WESTMORELAND.

The 2021 edition was judged by authors Otessa MOSHFEGH, Deerek OWUSU, and Isabel WAIDNER.

A pamphlet collating all shortlisted stories, published by Desperate Literature, can get got HERE as a PDF (and a print copy, preordered).

With thanks to Terry CRAVEN and the prize team, Layla BENITEZ-JAMES, Dom CZAPLA, Charlotte DELATTRE, Robert GREER, Kate McCULLY and Emily WESTMORELAND.

Katie HALE’s debut novel, MY NAME IS MONSTER (Canongate, 2019), was shortlisted for the Kitschies Golden Tentacle Award, and has been translated into multiple languages. A MacDowell fellow, she is also the author of two poetry pamphlets, and has written for theatre and immersive digital performance.

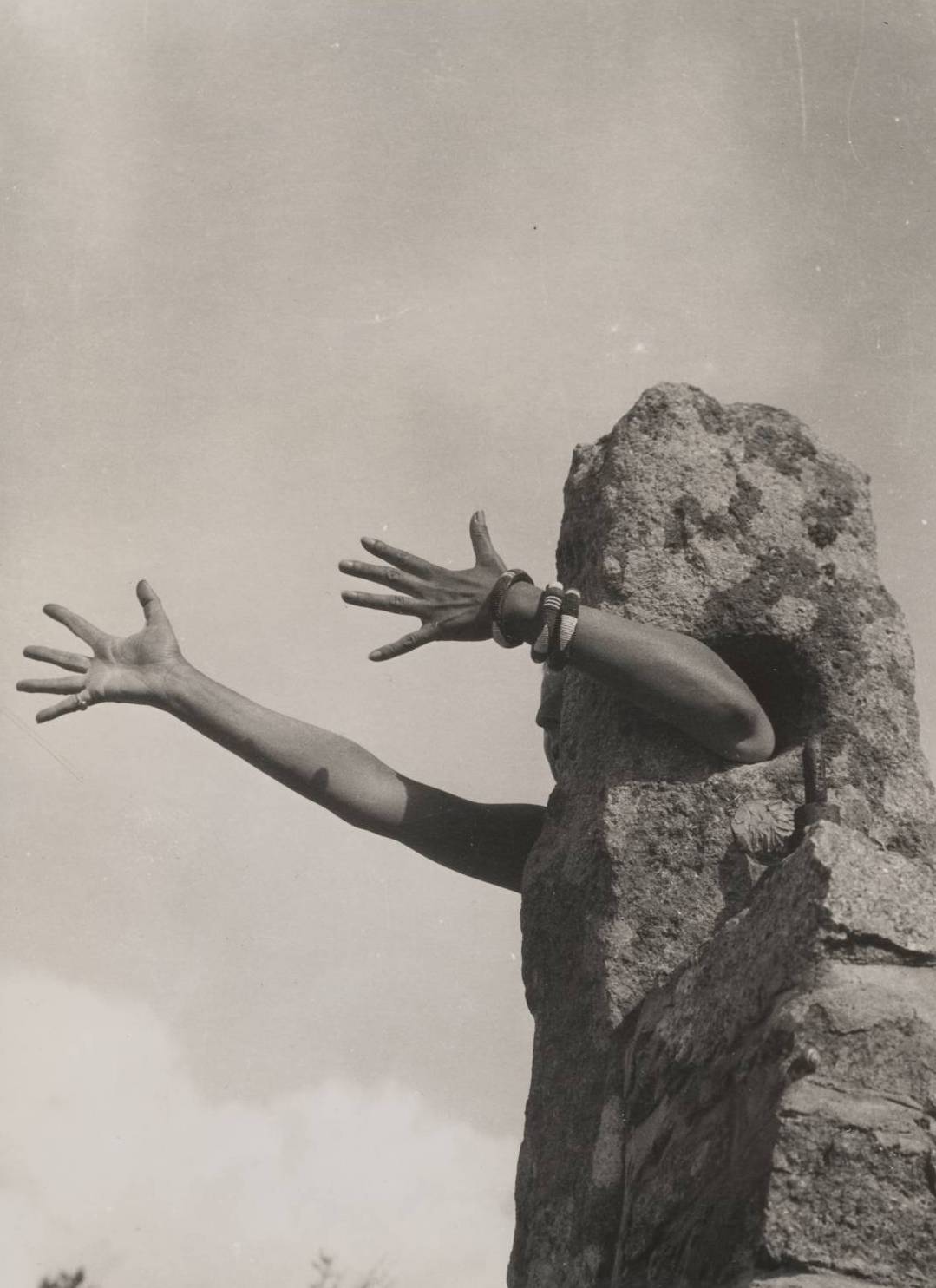

Image—

Claude CAHUN, ‘I Extend my Arms’ (1931 or 1932)

© The estate of Claude CAHUN