HOKUSAI

OR

WHERE GHOSTS APPEAR

Duncan WHITE

‘A flash...

and then night’

— Charles BAUDELAIRE

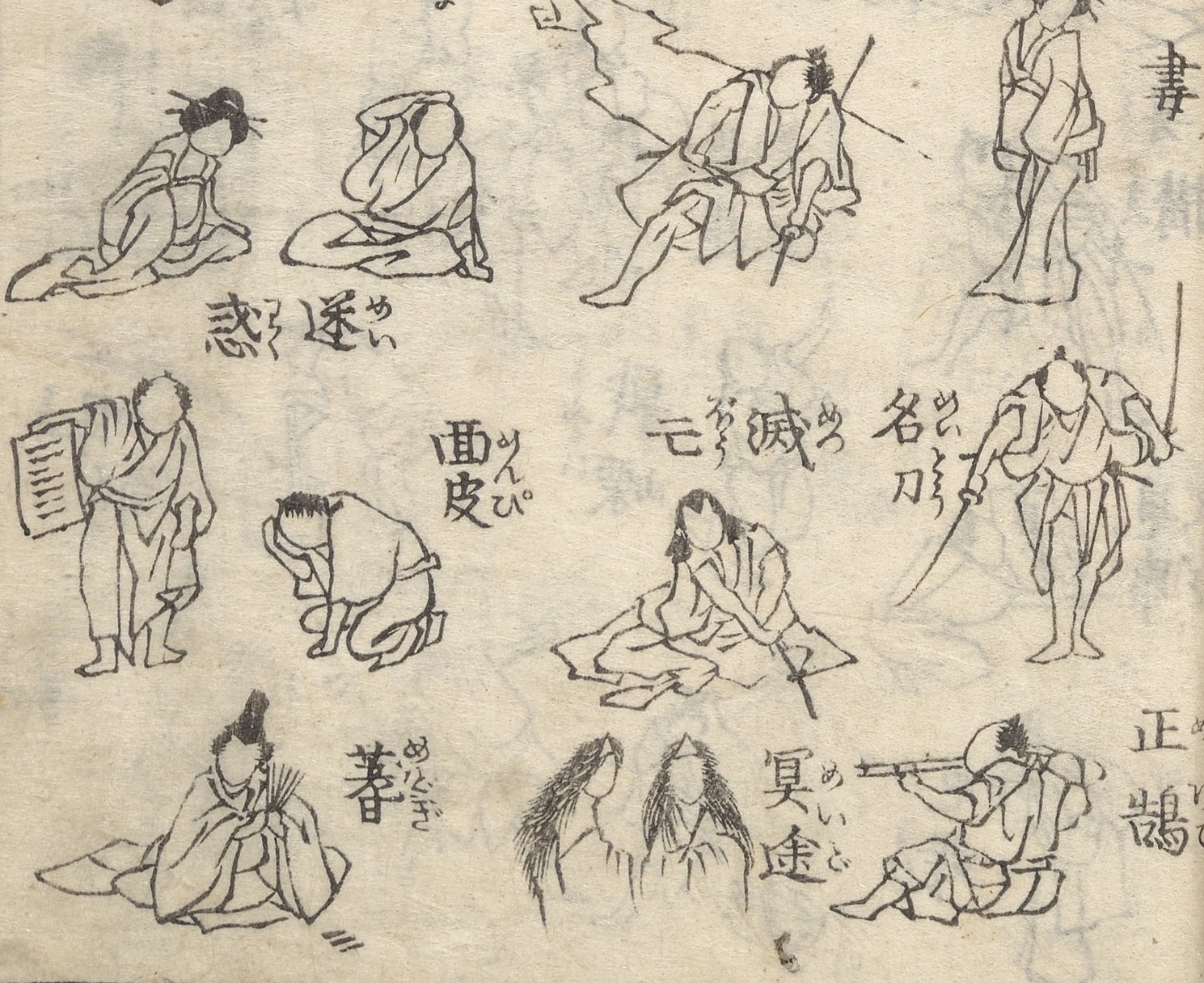

On the 1st day of the fourth month, 1810, Katsushika Hokusai was hit by lightning. How exactly Hokusai passed this particular morning in Katsushika province, cannot be known. At all events his sombre mood of the previous weeks and months appeared not to have lifted when, sometime after breakfast, he found himself making his way along the old carriage tracks, unsure whether O. would be reading or drawing (a thought that made him wince) or moving through the house and its garden engaged in tasks that were, to O., perfectly ordinary but to others appeared magical and strange. What is known, is that these movements of O., the precise personality of her gestures, obsessed Hokusai and that he used what he observed of them frequently—not that anyone would know—in his many drawing dictionaries of people at work. None of these depictions of blank-faced individuals resembled O. in the conventional sense but Hokusai believed, within the mannerisms others assumed to be particular of O. and of O. alone, it was possible to observe human traits otherwise hidden from conscious life. Hokuasi looked up to see two black birds lifting into the sky attempting it seemed to him to give some shape to the morning’s already oppressive warmth. Wiping a drop of sweat from his ear Hokusai continued in a trance as if all stories begin with somebody dreaming.

![]()

![]()

It is fair to assume, given his custom that Hokusai was late. The middle-aged painter had taken upon himself to conduct a drawing lesson each week at the house of O.’s mother on those days when O. was alone, so that, as he hurried through the countryside beyond the city walls he might perhaps have pictured, (although none of us can say for certain), the neatly ordered rooms, the garden O. tended tirelessly and the books she loved to read including the painting manuals Hokusai knew she was hiding from him and which he had insisted she destroy.

At the side of the road, he cursed himself as a herdsman passed with his stock, knowing, at this rate he would never catch her drawing directly from the teachings of antiquated dullards. He remembered how on the previous new year’s day marking his fiftieth year O. had prepared cakes made with yuzu fruit and sweet wine, but Hokusai passed on both choosing instead to lecture O. on the life-giving qualities of abstinence—at least in matters of food and drink—with such animation that he disturbed the carafe causing its contents to spill over a brand new set of manuals. O. bit her tongue. Moved in her heart by an old man’s watery eyes and trembling hands, she insisted it didn’t matter, and, clearing the mess, left Hokusai alone to recover. On her return, O. couldn’t help noticing the painter’s bright youthfulness as he looked up at her and that his hands, shaking only a moment before, lay perfectly still in his lap.

On approaching the valley where O.’s mother had a house, Hokusai regretted the New Year’s Day deception and his thoughts jumped, as they often did at that precarious age, to his new name. His publisher, Yeijudo, had mocked him. No matter how many names you take, how many times you are born, you’ll end up like the rest of us, Hokusai, rotting in the ground! And it was true, Hokusai would take many aliases throughout his long life leaving behind a disconnected procession of ghosts instead of any coherent biography, each title, once exhausted of its possibilities, to be discarded like a skin eclipsed or effaced by the man who came after it in the manner of a fugitive on the run denying at every opportunity the facts and details of his previous existence. Don’t listen to him, ___, the woodcarver, said. Your pictures will live on in the minds of everyone. Hokusai can never die. Eyeing him with some suspicion Hokusai tried to hide his thrill at seeing himself like a phantom of the future haunting the rooms of millions of unknown souls. But still, as he walked on under a darkening sky, the words of his publisher filled him with dread. He tried, as was his custom, to test whether the trees in the distance, or Yoshida’s woodshed, or the fishing boats far off on the Sumida River were the same as those he had seen the previous week. Reassuring himself that, if anything, he could see further than he ever had, he felt for his pulse, thrust his knees toward his chest and twisted suddenly at the waist so that anybody observing from a nearby hill might think the old and eccentric Hokusai was dancing or being attacked by bees.

At the banks of the Sumida Hokusai stopped to observe the dark waters passing under the bridge where the obscurity of changing shapes formed into sights even the great novelist of their age, Takizawa Bakin, would struggle to put into words. Hokusai smiled, looked up to the house and continued, more quickly now, there was so much to be done.

As the first raindrops fell, he put his hand on O.’s gate. There was a flash followed by a sound he later likened to the hum of butterfly wings. For a moment Katsushika Hokusai thought he was dead.

The door clicked in its frame as O. came in from the garden the scent of freshly cut mustard clouding her senses in mock imitation perhaps of the gathering storm clouding the sky over her house. She laid the two-pronged fork, leather-handled trowel and a short hooked knife next to a stack of books, several still in their wrappers. There are some rooms in which a relaxed orderliness creates an atmosphere of mysterious calm, largely because the key or code for deciphering this inner logic remains hidden. Hokusai often mocked O.’s tidiness for precisely this reason—as if it was an act of personal deception on her part—and liked to move things around when she wasn’t looking. Only the week before she had spent the entire morning hunting her comb, which she eventually discovered by chance in the kitchen hanging among her cooking tongs. It’s difficult now to say exactly how the room would have appeared except to pick out certain details that might have caught the eye of a visitor. There may have been intentional idiosyncrasies such as the empty birdcage, for instance, hanging in an open window but others may have evaded oblivion merely by chance. These might include, perhaps, the freshly cut mustard stalks abandoned for the time being beside an open copy of a popular painting manual which just so happened to be named after the mustard seed garden of a 17th Century Chinese playwright who longed all his life to paint the well-tended spaces surrounding his house perched precariously at the top of a rocky outcrop. Having no idea how to depict in lines and colours either the garden or its vertiginous views of the Zhejiang Province below, the playwright commissioned Wang Gai, a well known landscapist, to set down in clear and precise instructions a path to achieving his dream. It is not clear if the book was a success or if the playwright ever managed to achieve his painting but it is still possible to see the so-called Mustard Seed Manual, a survivor as it were from that lost time, in the British Museum where today’s visitor might well wonder on examining the displays on Russell Street whether it was the same copy that lay open on O.’s desk that morning in Katsushika on the day her father was hit by lightning.

Without sign of her teacher and impatient to begin, O. wetted a brush in ink and stood for a moment over a length of paper unrolled along the floor before kneeling to mark out a set of swift clear lines. She stood upright and stepped to the left before bending once more to her knees in order to repeat the strokes. Again she stood upright and stepped once more to the left. O. reproduced this action a further seven times so that by the time she had completed the task the sheet resembled a lost roll of film. Then she sat, as instructed, with her back to the scroll, looking out beyond the veranda to where the sky had blackened in the south and west and the smell of rain came into the house from fields across the valley. There were often storms at this time of year. On some days it would rain on one hillside but not on the other. She and Hokusai often remarked on this eccentricity of the countryside and laughed out loud as their neighbours ran for cover while they stood in O.’s garden bathed in light. O.’s eyes fell on the painting manual that so disgusted Hokusai. She knew he planned to publish his own manual, refuting the Chinese teachers and that he had hundreds of instructional drawings already prepared. We learn by copying, Hokusai was fond of saying, but you must copy the right thing. Even Hokusai, the master of improvisation on discovering a new and apparently boundless freedom since the Shogun had championed his work, resorted at times to a compass and square in order to establish the underlying form of a composition. O. knew he was a cheat as much as anyone in his line of work—but he was a wondrous cheat.

Returning to her feet, O’s drawings appeared to her like identical points on a compass in a land where all coordinates lead to the same house. But on closer inspection it was possible to discern slight discrepancies: the length of a curve; a line fuller in one place than in its equivalent three versions on; the shape of a teardrop absent in one drawing but identical where it appeared in the others. For a moment O. wondered if they were the work of someone else, some imposter who had completed the exercise while she was asleep. O. grimaced and looked away. As a draftsman, she knew that Hokusai understood drawing to be not simply a show of dexterity or a matter of illustrating a scene. He did not produce accurate copies of the world—he made the world more like itself. Hokusai often said: We only experience reality through the pictures we make of it.

A sound outside made O. look up. Wondering if one of the goats had taken ill she went to the window and looked out. Instead of a sick animal she could see her father—Katsushika Hokusai—lying by the gate his left arm twisted awkwardly behind his back as if he had been dropped from a great height. O. had never seen anything lie so still. She rushed to the door, throwing it open where, to her horror, she all but ran straight into Hokusai, standing in the doorway.

O. glanced to where she had seen her father’s body from the window a moment before realising in that instant that her father was dead and that this floating simulacrum in the entranceway to her mother’s house was Hokusai’s ghost.

Much later, feeling once more quite fit and well, the great Hokusai would not have been able to tell O. whether, in the moments after the lightning strike, he had been alive or dead. I remember seeing Bakin, he told her. He appeared to be standing over me—that traitor—as I lay there, a strange expression on his face. But the novelist had aged drastically so that he might fade at any moment into dust making Hokusai wonder if he was in fact seeing the end of times. I saw many of my illustrations—some I had been working on only that morning—alive in front of me, he said. The Kabuki actors Ichikawa Danjuro and Iwai Shijaku, their aliases Soga no Goro and Kewaizaka no Shosho; a bearded samurai, his sea serpent shaped penis entering the swollen vulva of a smiling maid—hordes of these Lilliput-like figures, each of whom I had once drawn, seemed to be crawling about in the grass beside my face, along my arms and legs. This can’t have been pleasant for Hokusai. The novels of Bakin, like many of the time, were invariably based on tales of revenge or jealousy, the mainsprings of most Japanese stories, and are filled with murders, suicides, violence in every shape and form, not to mention phantoms, transmogriphications and all manner of supernatural phenomena. But perhaps, it occurred to Hokusai, these hallucinations were not signs of mortality so much as mortal signs—pictures detached from the meaning of words. The last time he had seen Bakin the novelist in the flesh, as it were, he and Hokusai had argued bitterly. Bakin complained there were too many illustrations—that Hokusai’s pictures were taking on a life of their own, that his disconnected, anarchic drawings—what De Goncourt called: cette avalanche de dessins, cette debauche de crayonnages—had ceased to adhere faithfully to the plot. Hokusai pointed out it was his illustrations that made the books so popular—most of the people who bought the books couldn’t read Bakin’s stories even if they had wanted to. But they understand my pictures, he screamed. My pictures mean more than those empty words, fixed and dead, that always say the same thing and never change. Was he calling Bakin a hack, the novelist wanted to know? But Hokusai only shrugged turning his attention to the publisher insisting he use Sori Ga to cut his drawings from now on— the publisher’s block cutter makes too many mistakes, Hokusai complained. In the last printing arms and legs of the background figures had vanished as if they had evaporated in the transformation from one medium to the next. Sometimes, Hokusai went on, whole figures— peasants, animals even birds—have disappeared. Far worse for Hokusai to bear, there were instances in which the woodcutter had taken it upon himself to add a character of his own! In one book, a boat that looked more like a sleeping dog had mysteriously taken up residence in no less than half-a dozen river-views provoking a violent frenzy in Hokusai who burst in on the printers and demanded they cease immediately. The publisher, ushering Hokusai into his office, could only apologise. There was nothing he could do, the books had been released into the stores of Edo and Hokusai had to live from then on with the humiliation that these pictures signed with his name were no longer his own. As he lay in the grass at the mercy, or so it seemed to him then, of a history of images rushing through his mind, Hokusai reflected on his life-long struggle for control, autonomy and freedom. Yet here he was now, unable even to move, struck down by an arbitrary and unforgiving universe.

And so they are ever returning to us the dead. But the dead came back O. knew, as she stared at Hokusai’s ghost, because of the guilt of the living. She also knew her eyes could not be trusted. What happens, Hokusai used to say, when you draw a tree? You study the tree for many minutes, hours even, never averting your gaze, concentrating completely and then, for a moment, you look away to begin your drawing and in that instant the tree is gone, obliterated, in its place: a white empty field. How many leagues of snow and ice, of desolation, the very mists of what is and isn’t real must you now cross just to get back to your tree? Finally, one is made to realise, of course, he said, that it wasn’t a tree at all. It was just a picture of a tree. A picture nobody else could see, on the verge of being lost until you found a way to draw that other living, trembling thing, he said. Not the tree as such, but the journey to the tree, the journey away from what you have seen.

![]()

![]()

Too terrified to look away for fear, in part, he might disappear entirely, O. was attempting to remember Hokusai’s words regarding the world fabricated by her eyes, when she noticed that the ghost seemed to be hovering in the doorway like a reflection in a lake as if its clothes were illuminated by some unseen source. The ghost reminded her of a Kabuki actor she adored, who, hovering as it were under the dim candlelight of the stage, was made to freeze at the high point of every action so that the audience peering through the gloom could make out exactly what was written on his face. O. was quite startled until she realised on closer inspection that Hokusai’s tunic was in fact alive with ants panicked at their earthly world having been turned, as it were, on its head. She rushed forward to brush wildly at Hokusai’s garments—which she knew were not real—scattering the ants so that several landed in the freshly painted ink where they began to stick and drown. As she did so an ant bit her hand. In an instant, the land of imagination was invaded suddenly by cruel reality the way a dripping roof can make those sleeping beneath dream of rivers or waves out to sea.

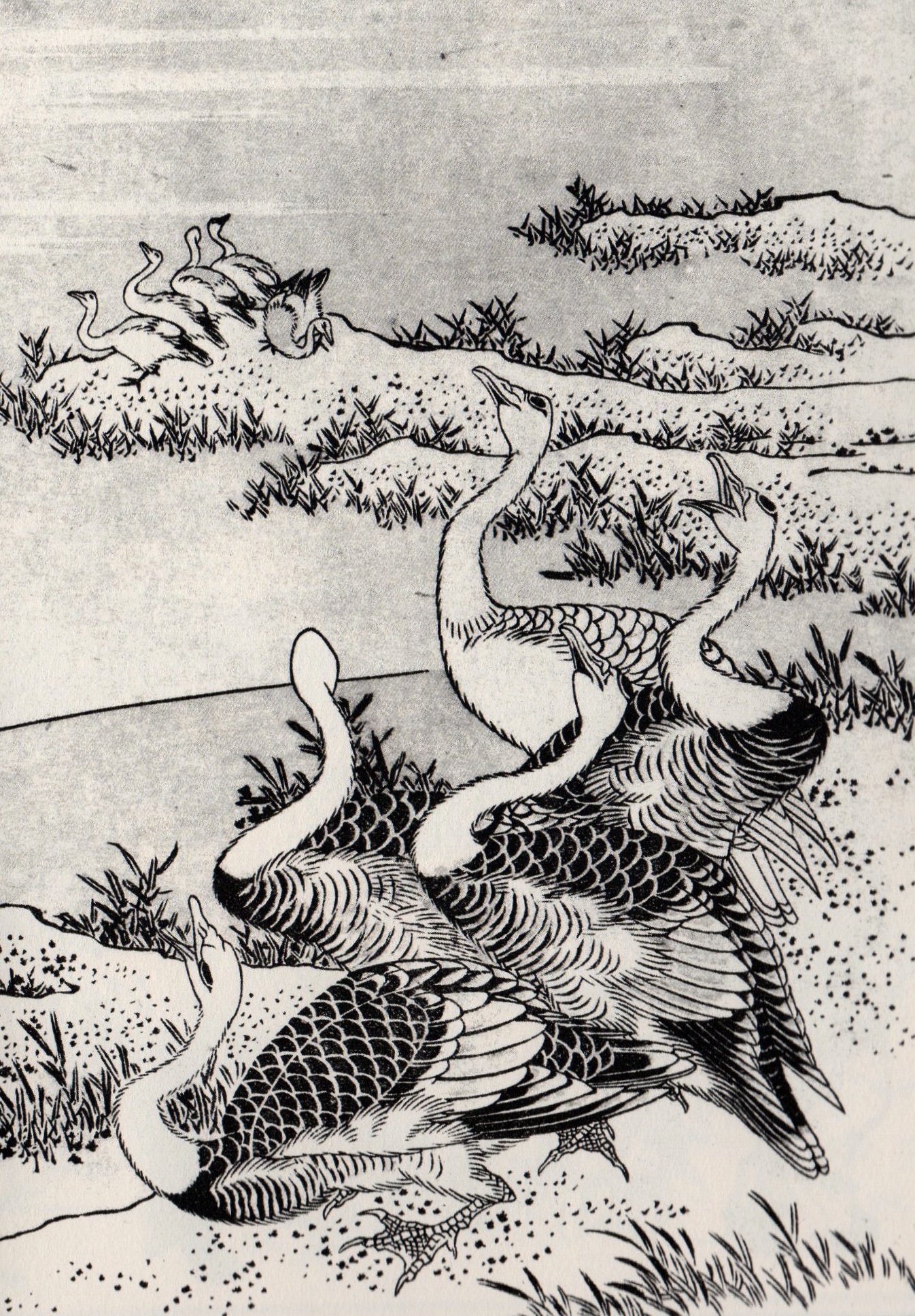

Observing the insects trapped in the ink O. was transported back to Hokusai’s triumph over the artist Shanzaro Buncho summoned to compete with him several years before in the presence of Shogun Iyenari in the grounds of the Gokodkuji temple in Edo, where an aunt told her afterwards, her father’s immortality had been sealed forever. It is not recorded what Buncho drew but using a brush the size of a besom and great bowls of Chinese ink, Hokusai painted the curves of a river so wide that only by viewing it from the rooftops could observers make out what Hokusai had drawn. He then forced the largest cockerel he could find, whose feet he had daubed in blood red ink, to run over the paper and entitled the work: River Tastuta in autumn, with maple leaves floating downstream. So profoundly was her heart stirred that, as the painting continued, tears came repeatedly to her eyes, so that O., who could not have been more than six or seven years old at the time, watched on through a watery haze that seemed even now to best represent her father’s impossible world.

In one of Hokusai’s illustrations for the novels of Bakin, a craftsman (or perhaps, a priest) is visited by the ghost of his daughter, and it is hard not to liken what O. may or may not have seen on that morning after the lightning strike in Katsushika, with the purely fictional scene drawn by Hokusai several years earlier in 1806, so that one has to wonder if memory and art had, as it were, ransacked the mortality of perception.

So many of Hokusai’s works claim to be based, however fleetingly, on the facts of observation. There are the river views, the villages under snow, the Fine Views of the Eastern Capital at a Glance, not to mention over a hundred and fifty or so views of the volcano, Fujiyama.

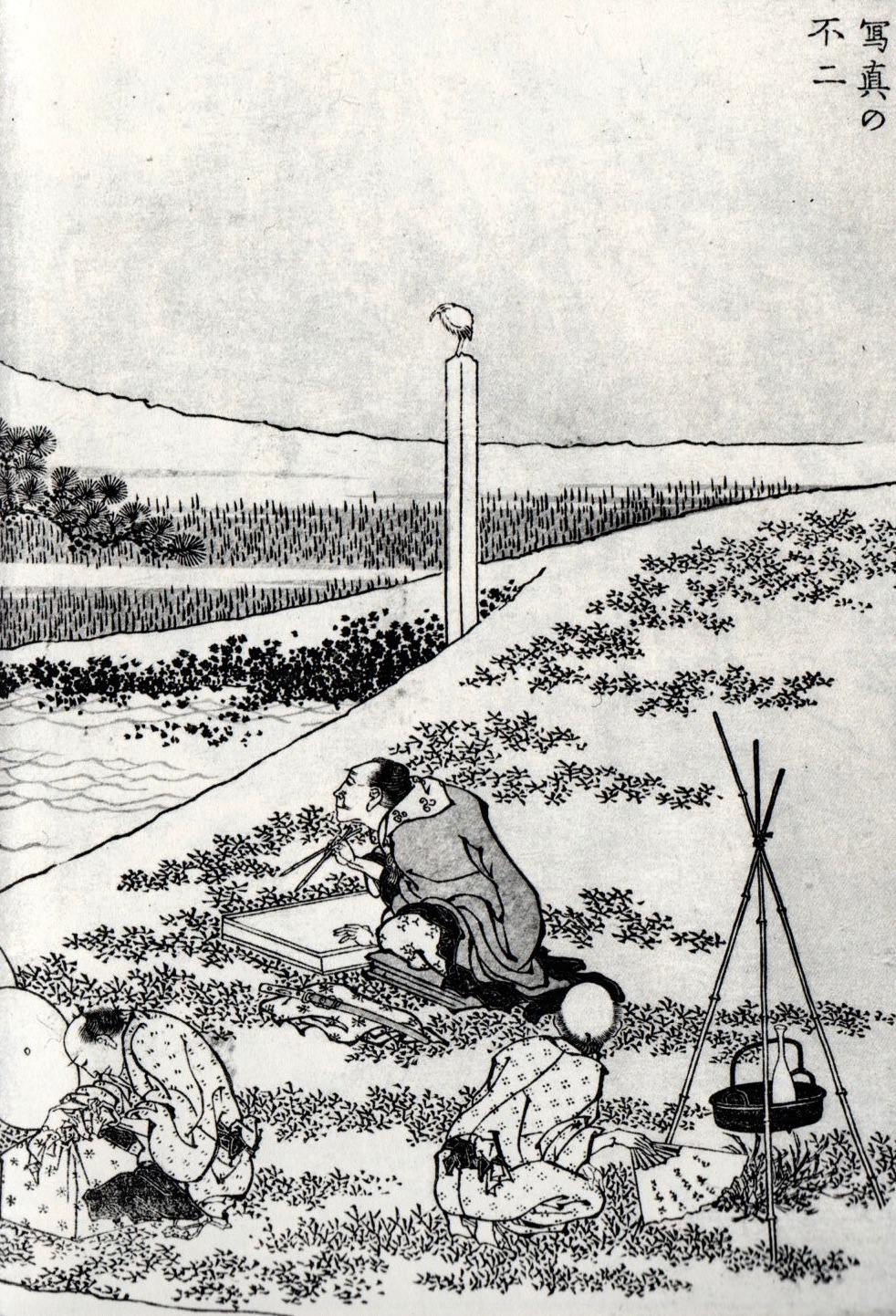

Hokusai, like many artists of the time gleefully embraced, it would seem (according, at least, to this picture), the benevolent role of the travelling collector who would go to any lengths to capture the well-loved panoramas of Japan (although Hokusai never enjoyed the luxury of his travelling alter-ego). He was the eyes, so to speak, of all those men and women with neither the time nor the resources to witness for themselves the treasures of the wide kingdom, derived, one way or another, from the well-thumbed guidebooks of the time showing street scenes, acts of daily commerce, picnic parties in the country suburbs, each recalling in turn the recognisable features of any given district—the cushion pine in Aoyama, the red Castle at Osaka or the Water-wheel at Onden. Yet very few of Hokusai’s own real-life views correspond with reality. Take this picture in which we are shown the volcano from Edo Bay close to Omori beyond the bamboo fields where seaweed is cultivated, each reed pointing the eye upwards to the hovering form of Mount Fuji above. The view is believable enough except that the two boats used it would seem merely to illustrate Hokusai’s skill with perspective—or is it to lampoon the realism of the Dutch prints of Nagasaki?—must have been imported from another scene neither boat being the kind of vessel nori farmers would have used to harvest their crop in those long forgotten days. Looking back on these pictures it is no wonder observers might ask whether Hokusai had ever in fact been to the places he is escorting us to and if instead we are being shown a scene from where nobody was standing; from the point of view of a ghost, one tormented by what he cannot remember, of a reality he had no interest in attempting—through art or otherwise—to possess.

![]()

![]()

On the roof, big splats of rain or was it hail began to fall and O. was brought back to herself by the noise of material things. She felt quite sick and thought she might collapse but then this struck her as a silly thing to do. Instead she reached out to the ghost and handed it her brush. For a moment the ghost looked straight through her as if it was in fact nothing but the shell of a dead and empty soul that had in its rush to escape the trappings of life quite forgotten or perhaps purposely abandoned its now redundant countenance. Just as O. thought she might indeed pass out, Hokusai’s dead eyes snapped into focus, his gaze holding her fast and she felt herself resolve once more into an image as if the inattentions of the dead could, like a mirror that has blown, suck away the self-absorption of the living.

Hokusai brush in hand bent down and began to attack with stabbing movements, the studies O. had been working on that morning before the day had been so rudely derailed, it seemed to her, by the presence of the ghost. This was something that in his living form Hokusai had never taken it upon himself to do; he had never wrested her work from her in an attempt to complete or alter what she had or hadn’t done. Watching the old painter from beyond the grave, the scene suddenly appeared quite ridiculous to O. as if she were watching an image—a ghost was after all nothing but an image albeit one without a medium, except, perhaps, the mistakes of the living— attempting to wipe out an image. The absurdity of the notion, like watching a child stamp on insects simply to satisfy their own amusement, filled O. with a sense of anger and dread, and she wondered if this might all be a trick of her own imagination, that she might be in fact seeing an illustration from one of Hokusai’s books brought back not from where it rested on her shelves but from between the grey blanks of her memory, from among so many objects and moments that existed on the verge of being gone.

In some of his Volcano pictures, Hokusai goes so far as to depict scenes neither he nor anybody alive would have seen. These views are not reconstructed, so to speak, from the removed or distant vantage of historical imagination, but from within the very centre of the violent eruption itself so that the smooth passage through distant scenes is interrupted leaving the traveller stranded suddenly in the midst of earthquakes, hurricanes or tidal waves scattered through the pages of Hokusai’s books like fragments of a lost and exploded past. Perhaps the most striking of these is Hokusai’s close-up view of the last known eruption of Fujiyama in the late winter of 1707. In the dead of night so that the sleeping are blown into the blackness of an obliterated world, limbs cascading through the sky, animals thrown and buried under rocks and timbers, the dead—men women and children—are dragged on the backs of those who have survived; a vast shower of debris filling the air. It is a peculiar place to commence any journey, in the middle of the devastation of sleep, so that we start out in the vulnerable defencelessness of all dreamers at the heart of a world torn to shreds. While reminiscent of a scene from so many of the war films that would in time take its place—the atomic fate of the islands of Japan—it is difficult not to wonder to what extent Hokusai’s picture is less specifically an image of volcanic eruption—something Hokusai would never witness with his own eyes—than an utter demolition of the faith in picture-making. All so called natural disasters, Hokusai seemed to suggest, are only understood as such because of their intervention into the artificial landscapes of human design. A broken down house, a collapsed bridge, a road torn in half. It may in fact be the case that it is all but impossible to determine where one ends and the other begins. The last eruption of Fujiyama took place fifty years before Hokusai was born but the painter would have witnessed other moments of devastation—famine, war, earthquakes, his own house burning down—and perhaps he based his fantasy of devastation on the memories triggered by these events. Or perhaps, for that matter, the morning of the lightning strike had been playing on his mind, as it would so often be during the years that followed, when he set himself the task of bringing back the dead.

O. didn’t remember much of what happened next. The ghost may have vanished. He may have returned to a standing position, regarding her while receding somehow into the room. She may have blacked out for a moment and woken to find him gone. Either way when she discovered herself alone with Hokusai’s erasure of her work she flew into a violent rage tearing at shelves and overturning furniture. She picked up a stool and threw it at the wall with such ferocity that it splintered and crashed to the ground. She flung whole armfuls of books and scrolls in all directions scattering plants and instruments, pots and pans. Once the room had been uprooted she began to tear at her own body, her clothes and her hair, striking her face and chest so that great welts opened up on her skin. Exhausted and blood stained she finally collapsed among her brushes and the spilled inks. She came to as it were to find herself pulling the fork she used to tend the garden slowly through her hair straightening the tangle that had come loose across her shoulders and neck.

![]()

![]()

The most striking of these screenings is perhaps the ninety ninth view of Fuji seen through a knothole in a pair of shutters drawn against the early morning sun where a cleaner is working, the volcano’s image inverted by a well known trick of the light, reappearing as a ghostly projection, the trembling disc showing a true and accurate likeness of the mountain—only here it is inverted, turned on its head, cast as it might have been however briefly onto the translucent paper of the Shoji opposite. Hokusai could not resist such tricks of nature, the visual pranks he encountered everywhere partial, as he always had been, to any attempt to defraud the academic universe. The same academics would quarrel endlessly over certain details, why for instance is there a shadowy second image of the volcano within the first but the real question might be why has this scene – number ninety-nine of the one hundred views—been set as the penultimate view of the book? Perhaps Hokusai conceived of all endings as a form of beginning, realising as he must have done that he would pass on soon enough and that pictures and picture-making would transform to such an extent that the actual world he knew so intimately would disappear for good.

![]()

He could have gone up in a puff of smoke, he later explained to O. Vaporised. Lost to the reality of the same fleeting moment to which he was so enthralled! Look at the great Utamaro, he told O: Not long in the ground. His teachings abandoned. His paintings and prints diminished by poor copyists. In Edo’s brothels even, where Utamaro had been well known, nobody could remember his name. His mind buzzing, Hokusai stared blankly into the grass beneath his nose, absorbed like a child in the miniature universe moving through the foliage: ants, centipedes, worms as if they were negotiating the streets and alleyways of an invisible hell. A world caught between one time and another. A ghost world made only of pictures and signs.

O. sensed the way all children do that her father’s disappearance would not be like her own. Putting down the fork and tying back her hair she began to search through the debris with the same peculiar precision that made acquaintances think she was unlike other people. Anyone passing at her door would assume she was some final survivor of the devastation left by an earthquake in the night. Here and there she paused to pick up a book, say, or a flint stone for lighting the stove, raising it to her face for inspection then putting it down again as if each of the things she touched was somehow coming back to life and could now be abandoned to live in freedom, alone. It was in fact a Farewell. She would go and live with Hokusai in Edo. She would train and work as an artist. She would leave everything behind.

Hokusai wasn’t dead, O. thought to herself as she set out along the road. The trees were bent and dripping everywhere as if it wasn’t a thunderstorm but a great tidal wave that had swept through the fields and woods. Neither was Hokusai living, she thought. Like a portrait made at the instant he was gone, the electrocution had thrown Hokusai out of his body and into the room where O. was waiting for him, an image transmitted or projected somehow across time and space. Or at least that was what Hokusai wanted her to think. He would live from then on in the imagination, she realised, returning to the mind again and again like Fuji, visible, people liked to say, from every bend in the road. If it wasn’t true in nature it was of course true in fact: Fuji appeared in wall decorations, on reproductions in houses, on streets, on fans, on trays, on screens, on almost every article, whether for use or ornament, the bold shapely lines of the mountain have been drawn. Just as people saw it in their dreams, in their prayers, or read about the volcano in legends, there is hardly a garden or a park throughout Japan from where Fuji cannot be seen. Like a long since forgotten story from a world where nobody now knew how to live, anything that was real, O. thought, as she passed along Edo’s streets, had to disappear.

I thought you were dead, O. said. You frightened me.

Hokusai laughed. Yes you took it very badly. I presumed you had gone mad with fear.

Later O. would ask: What was it like?

Hokusai smiled, looking away. I can’t remember, he said.

In Edo, working under Hokusia’s other apprentices—all boys—jealous of her skills with a brush, O. liked to assume there might be two-sides to a person as she observed the now ancient Hokusai, often drawing late into the night, his body so thin it looked as if it might crumble under the weight of his blanket. How he kneels there, bent over his table, scrutinising the paper just as intently as he does the objects around him by day; how he stabs away with his pencil, his pen, his brush; how he spurts water from his glass to the ceiling and dries his brush on his shirt; how he pursues his work swiftly and intensely, as though he were afraid his images might get away from him. He is combative, even when alone, she thought, parrying his own blows.

Hokusai looked up to the opposite side of the street. The dirty facades and drawn shutters seemed so close that the view through his filthy window looked as flat as a picture. A Dutch print showing a river landscape was tacked to the wall of his studio. In a rare note to himself, Hokusai would write: We render the form and colour without indicating relief. But in the European method, they attempt to give relief to everything and deceive our eyes. In truth Hokusai would leave very few of these thoughts behind. In the final years of his life Hokusai was said to draw a Chinese lion each morning, throwing it out of the window to ward off ill luck. O. secretly collected these drawings from the street into a book she entitled, Destroy All Monsters. But even this daily record has long since disappeared. Hokusai kept no diaries, no journals were made, few people asked him about his work and if they did, nobody wrote it down. The evidential phenomena of an individual life not of the concern it would muster two centuries on.

During the final weeks of his life Hokusai’s sight had begun to fail and he was prone in the evenings to hallucinations and painful tremors in his arms and legs. He ate very little sustaining himself on sweet tea and wine. Finding himself living more and more in the past he often returned as it were to the lightning strike of which he had no real recollection and where—as if it were an actual place one might be able to locate on a map—he liked to boast there had been no before or after. One evening he worked more frantically than normal, his hands trembling he spilt water and inks as he stabbed more and more desperately with his brush. At one point he heard something move behind his door. As it opened he glimpsed O. in a mirror hanging above his desk. When he turned, his daughter was nowhere to be seen and the entrance to his room was empty and dark. There was only the open window the same window he cast drawings out of each morning to keep the gods away from his door. The following day Hokusai was found dead at his desk. His heart had failed. He would have been ninety-one in a few weeks time. His room, thick with dirt and dust, appeared to those who found him like the site of some great catastrophe. Only his worktable offered signs of order and calm. A hair comb lay among the inks and brushes that had been neatly put away. The object struck many as strange, particularly given that Hokusai, in death as in life, had not a single hair on his head.

After Hokusai’s death, O. disappeared from record. Some say she joined the theatre. Others report she went blind and took to begging in the street; while others claim she became pregnant, developed complications and died giving birth. Whatever the details of her life, it is no doubt the case that O. lived through the rest of her days in possession of her most treasured of Hokusai’s views, the original having been taken from the room where Hokusai worked sometime before his death. It is still possible to read the description of A Thunderstorm At the Foot of Mount Fuji written in England many years later after both O. and Hokusai were dead:

Duncan WHITE’s book Never Connect was shortlisted for the Fitzcarraldo Editions Novel Prize and will be published by Holland House Books in November 2020 under the title: There’s A Certain Slant of Light. “Hokusai, or Where Ghosts Appear” is taken from his new work in progress, Lightning Stories. His poetry, stories and critical writings have appeared in various magazines and journals. He lives and works in London, where he also runs the MRes Art Moving Image course at Central Saint Martins.

It is fair to assume, given his custom that Hokusai was late. The middle-aged painter had taken upon himself to conduct a drawing lesson each week at the house of O.’s mother on those days when O. was alone, so that, as he hurried through the countryside beyond the city walls he might perhaps have pictured, (although none of us can say for certain), the neatly ordered rooms, the garden O. tended tirelessly and the books she loved to read including the painting manuals Hokusai knew she was hiding from him and which he had insisted she destroy.

At the side of the road, he cursed himself as a herdsman passed with his stock, knowing, at this rate he would never catch her drawing directly from the teachings of antiquated dullards. He remembered how on the previous new year’s day marking his fiftieth year O. had prepared cakes made with yuzu fruit and sweet wine, but Hokusai passed on both choosing instead to lecture O. on the life-giving qualities of abstinence—at least in matters of food and drink—with such animation that he disturbed the carafe causing its contents to spill over a brand new set of manuals. O. bit her tongue. Moved in her heart by an old man’s watery eyes and trembling hands, she insisted it didn’t matter, and, clearing the mess, left Hokusai alone to recover. On her return, O. couldn’t help noticing the painter’s bright youthfulness as he looked up at her and that his hands, shaking only a moment before, lay perfectly still in his lap.

On approaching the valley where O.’s mother had a house, Hokusai regretted the New Year’s Day deception and his thoughts jumped, as they often did at that precarious age, to his new name. His publisher, Yeijudo, had mocked him. No matter how many names you take, how many times you are born, you’ll end up like the rest of us, Hokusai, rotting in the ground! And it was true, Hokusai would take many aliases throughout his long life leaving behind a disconnected procession of ghosts instead of any coherent biography, each title, once exhausted of its possibilities, to be discarded like a skin eclipsed or effaced by the man who came after it in the manner of a fugitive on the run denying at every opportunity the facts and details of his previous existence. Don’t listen to him, ___, the woodcarver, said. Your pictures will live on in the minds of everyone. Hokusai can never die. Eyeing him with some suspicion Hokusai tried to hide his thrill at seeing himself like a phantom of the future haunting the rooms of millions of unknown souls. But still, as he walked on under a darkening sky, the words of his publisher filled him with dread. He tried, as was his custom, to test whether the trees in the distance, or Yoshida’s woodshed, or the fishing boats far off on the Sumida River were the same as those he had seen the previous week. Reassuring himself that, if anything, he could see further than he ever had, he felt for his pulse, thrust his knees toward his chest and twisted suddenly at the waist so that anybody observing from a nearby hill might think the old and eccentric Hokusai was dancing or being attacked by bees.

At the banks of the Sumida Hokusai stopped to observe the dark waters passing under the bridge where the obscurity of changing shapes formed into sights even the great novelist of their age, Takizawa Bakin, would struggle to put into words. Hokusai smiled, looked up to the house and continued, more quickly now, there was so much to be done.

As the first raindrops fell, he put his hand on O.’s gate. There was a flash followed by a sound he later likened to the hum of butterfly wings. For a moment Katsushika Hokusai thought he was dead.

The door clicked in its frame as O. came in from the garden the scent of freshly cut mustard clouding her senses in mock imitation perhaps of the gathering storm clouding the sky over her house. She laid the two-pronged fork, leather-handled trowel and a short hooked knife next to a stack of books, several still in their wrappers. There are some rooms in which a relaxed orderliness creates an atmosphere of mysterious calm, largely because the key or code for deciphering this inner logic remains hidden. Hokusai often mocked O.’s tidiness for precisely this reason—as if it was an act of personal deception on her part—and liked to move things around when she wasn’t looking. Only the week before she had spent the entire morning hunting her comb, which she eventually discovered by chance in the kitchen hanging among her cooking tongs. It’s difficult now to say exactly how the room would have appeared except to pick out certain details that might have caught the eye of a visitor. There may have been intentional idiosyncrasies such as the empty birdcage, for instance, hanging in an open window but others may have evaded oblivion merely by chance. These might include, perhaps, the freshly cut mustard stalks abandoned for the time being beside an open copy of a popular painting manual which just so happened to be named after the mustard seed garden of a 17th Century Chinese playwright who longed all his life to paint the well-tended spaces surrounding his house perched precariously at the top of a rocky outcrop. Having no idea how to depict in lines and colours either the garden or its vertiginous views of the Zhejiang Province below, the playwright commissioned Wang Gai, a well known landscapist, to set down in clear and precise instructions a path to achieving his dream. It is not clear if the book was a success or if the playwright ever managed to achieve his painting but it is still possible to see the so-called Mustard Seed Manual, a survivor as it were from that lost time, in the British Museum where today’s visitor might well wonder on examining the displays on Russell Street whether it was the same copy that lay open on O.’s desk that morning in Katsushika on the day her father was hit by lightning.

Without sign of her teacher and impatient to begin, O. wetted a brush in ink and stood for a moment over a length of paper unrolled along the floor before kneeling to mark out a set of swift clear lines. She stood upright and stepped to the left before bending once more to her knees in order to repeat the strokes. Again she stood upright and stepped once more to the left. O. reproduced this action a further seven times so that by the time she had completed the task the sheet resembled a lost roll of film. Then she sat, as instructed, with her back to the scroll, looking out beyond the veranda to where the sky had blackened in the south and west and the smell of rain came into the house from fields across the valley. There were often storms at this time of year. On some days it would rain on one hillside but not on the other. She and Hokusai often remarked on this eccentricity of the countryside and laughed out loud as their neighbours ran for cover while they stood in O.’s garden bathed in light. O.’s eyes fell on the painting manual that so disgusted Hokusai. She knew he planned to publish his own manual, refuting the Chinese teachers and that he had hundreds of instructional drawings already prepared. We learn by copying, Hokusai was fond of saying, but you must copy the right thing. Even Hokusai, the master of improvisation on discovering a new and apparently boundless freedom since the Shogun had championed his work, resorted at times to a compass and square in order to establish the underlying form of a composition. O. knew he was a cheat as much as anyone in his line of work—but he was a wondrous cheat.

Returning to her feet, O’s drawings appeared to her like identical points on a compass in a land where all coordinates lead to the same house. But on closer inspection it was possible to discern slight discrepancies: the length of a curve; a line fuller in one place than in its equivalent three versions on; the shape of a teardrop absent in one drawing but identical where it appeared in the others. For a moment O. wondered if they were the work of someone else, some imposter who had completed the exercise while she was asleep. O. grimaced and looked away. As a draftsman, she knew that Hokusai understood drawing to be not simply a show of dexterity or a matter of illustrating a scene. He did not produce accurate copies of the world—he made the world more like itself. Hokusai often said: We only experience reality through the pictures we make of it.

A sound outside made O. look up. Wondering if one of the goats had taken ill she went to the window and looked out. Instead of a sick animal she could see her father—Katsushika Hokusai—lying by the gate his left arm twisted awkwardly behind his back as if he had been dropped from a great height. O. had never seen anything lie so still. She rushed to the door, throwing it open where, to her horror, she all but ran straight into Hokusai, standing in the doorway.

O. glanced to where she had seen her father’s body from the window a moment before realising in that instant that her father was dead and that this floating simulacrum in the entranceway to her mother’s house was Hokusai’s ghost.

Much later, feeling once more quite fit and well, the great Hokusai would not have been able to tell O. whether, in the moments after the lightning strike, he had been alive or dead. I remember seeing Bakin, he told her. He appeared to be standing over me—that traitor—as I lay there, a strange expression on his face. But the novelist had aged drastically so that he might fade at any moment into dust making Hokusai wonder if he was in fact seeing the end of times. I saw many of my illustrations—some I had been working on only that morning—alive in front of me, he said. The Kabuki actors Ichikawa Danjuro and Iwai Shijaku, their aliases Soga no Goro and Kewaizaka no Shosho; a bearded samurai, his sea serpent shaped penis entering the swollen vulva of a smiling maid—hordes of these Lilliput-like figures, each of whom I had once drawn, seemed to be crawling about in the grass beside my face, along my arms and legs. This can’t have been pleasant for Hokusai. The novels of Bakin, like many of the time, were invariably based on tales of revenge or jealousy, the mainsprings of most Japanese stories, and are filled with murders, suicides, violence in every shape and form, not to mention phantoms, transmogriphications and all manner of supernatural phenomena. But perhaps, it occurred to Hokusai, these hallucinations were not signs of mortality so much as mortal signs—pictures detached from the meaning of words. The last time he had seen Bakin the novelist in the flesh, as it were, he and Hokusai had argued bitterly. Bakin complained there were too many illustrations—that Hokusai’s pictures were taking on a life of their own, that his disconnected, anarchic drawings—what De Goncourt called: cette avalanche de dessins, cette debauche de crayonnages—had ceased to adhere faithfully to the plot. Hokusai pointed out it was his illustrations that made the books so popular—most of the people who bought the books couldn’t read Bakin’s stories even if they had wanted to. But they understand my pictures, he screamed. My pictures mean more than those empty words, fixed and dead, that always say the same thing and never change. Was he calling Bakin a hack, the novelist wanted to know? But Hokusai only shrugged turning his attention to the publisher insisting he use Sori Ga to cut his drawings from now on— the publisher’s block cutter makes too many mistakes, Hokusai complained. In the last printing arms and legs of the background figures had vanished as if they had evaporated in the transformation from one medium to the next. Sometimes, Hokusai went on, whole figures— peasants, animals even birds—have disappeared. Far worse for Hokusai to bear, there were instances in which the woodcutter had taken it upon himself to add a character of his own! In one book, a boat that looked more like a sleeping dog had mysteriously taken up residence in no less than half-a dozen river-views provoking a violent frenzy in Hokusai who burst in on the printers and demanded they cease immediately. The publisher, ushering Hokusai into his office, could only apologise. There was nothing he could do, the books had been released into the stores of Edo and Hokusai had to live from then on with the humiliation that these pictures signed with his name were no longer his own. As he lay in the grass at the mercy, or so it seemed to him then, of a history of images rushing through his mind, Hokusai reflected on his life-long struggle for control, autonomy and freedom. Yet here he was now, unable even to move, struck down by an arbitrary and unforgiving universe.

And so they are ever returning to us the dead. But the dead came back O. knew, as she stared at Hokusai’s ghost, because of the guilt of the living. She also knew her eyes could not be trusted. What happens, Hokusai used to say, when you draw a tree? You study the tree for many minutes, hours even, never averting your gaze, concentrating completely and then, for a moment, you look away to begin your drawing and in that instant the tree is gone, obliterated, in its place: a white empty field. How many leagues of snow and ice, of desolation, the very mists of what is and isn’t real must you now cross just to get back to your tree? Finally, one is made to realise, of course, he said, that it wasn’t a tree at all. It was just a picture of a tree. A picture nobody else could see, on the verge of being lost until you found a way to draw that other living, trembling thing, he said. Not the tree as such, but the journey to the tree, the journey away from what you have seen.

Too terrified to look away for fear, in part, he might disappear entirely, O. was attempting to remember Hokusai’s words regarding the world fabricated by her eyes, when she noticed that the ghost seemed to be hovering in the doorway like a reflection in a lake as if its clothes were illuminated by some unseen source. The ghost reminded her of a Kabuki actor she adored, who, hovering as it were under the dim candlelight of the stage, was made to freeze at the high point of every action so that the audience peering through the gloom could make out exactly what was written on his face. O. was quite startled until she realised on closer inspection that Hokusai’s tunic was in fact alive with ants panicked at their earthly world having been turned, as it were, on its head. She rushed forward to brush wildly at Hokusai’s garments—which she knew were not real—scattering the ants so that several landed in the freshly painted ink where they began to stick and drown. As she did so an ant bit her hand. In an instant, the land of imagination was invaded suddenly by cruel reality the way a dripping roof can make those sleeping beneath dream of rivers or waves out to sea.

Observing the insects trapped in the ink O. was transported back to Hokusai’s triumph over the artist Shanzaro Buncho summoned to compete with him several years before in the presence of Shogun Iyenari in the grounds of the Gokodkuji temple in Edo, where an aunt told her afterwards, her father’s immortality had been sealed forever. It is not recorded what Buncho drew but using a brush the size of a besom and great bowls of Chinese ink, Hokusai painted the curves of a river so wide that only by viewing it from the rooftops could observers make out what Hokusai had drawn. He then forced the largest cockerel he could find, whose feet he had daubed in blood red ink, to run over the paper and entitled the work: River Tastuta in autumn, with maple leaves floating downstream. So profoundly was her heart stirred that, as the painting continued, tears came repeatedly to her eyes, so that O., who could not have been more than six or seven years old at the time, watched on through a watery haze that seemed even now to best represent her father’s impossible world.

In one of Hokusai’s illustrations for the novels of Bakin, a craftsman (or perhaps, a priest) is visited by the ghost of his daughter, and it is hard not to liken what O. may or may not have seen on that morning after the lightning strike in Katsushika, with the purely fictional scene drawn by Hokusai several years earlier in 1806, so that one has to wonder if memory and art had, as it were, ransacked the mortality of perception.

So many of Hokusai’s works claim to be based, however fleetingly, on the facts of observation. There are the river views, the villages under snow, the Fine Views of the Eastern Capital at a Glance, not to mention over a hundred and fifty or so views of the volcano, Fujiyama.

Hokusai, like many artists of the time gleefully embraced, it would seem (according, at least, to this picture), the benevolent role of the travelling collector who would go to any lengths to capture the well-loved panoramas of Japan (although Hokusai never enjoyed the luxury of his travelling alter-ego). He was the eyes, so to speak, of all those men and women with neither the time nor the resources to witness for themselves the treasures of the wide kingdom, derived, one way or another, from the well-thumbed guidebooks of the time showing street scenes, acts of daily commerce, picnic parties in the country suburbs, each recalling in turn the recognisable features of any given district—the cushion pine in Aoyama, the red Castle at Osaka or the Water-wheel at Onden. Yet very few of Hokusai’s own real-life views correspond with reality. Take this picture in which we are shown the volcano from Edo Bay close to Omori beyond the bamboo fields where seaweed is cultivated, each reed pointing the eye upwards to the hovering form of Mount Fuji above. The view is believable enough except that the two boats used it would seem merely to illustrate Hokusai’s skill with perspective—or is it to lampoon the realism of the Dutch prints of Nagasaki?—must have been imported from another scene neither boat being the kind of vessel nori farmers would have used to harvest their crop in those long forgotten days. Looking back on these pictures it is no wonder observers might ask whether Hokusai had ever in fact been to the places he is escorting us to and if instead we are being shown a scene from where nobody was standing; from the point of view of a ghost, one tormented by what he cannot remember, of a reality he had no interest in attempting—through art or otherwise—to possess.

The greatest views of course were those of the volcano, Fujiyama, which like the ghost confronting O. on the morning after the lightning strike, passes through Hokusai’s work as something so tangible so solid and real that it can stand at the crossing point of fiction and fact. Each picture—Fujiyama glimpsed through smoke, Fujiyama in a rain storm, Fujiyama through a screen or a gap between houses or this one of Fujiyama reflected in a lake—is as much an article of memory and dream as a record of real places, people and things. There is, for instance, the so-called view from Sodegaura but, as one writer has pointed out, it would have been quite impossible to see Sodegaura from this well-known outlook already made famous by pictures Hokusai published as a much younger man. There one can find the same rocky outcropping with Fuji rising to the right, the same cave cut into the rock, the same village nestled beneath the trees, the same islands extending into the distance. But now we are also asked to look for Sodegaura, a stretch of shoreline hundreds of miles further west, far out of range of human eyes. Was Hokusai losing his memory, one observer asks, or perhaps he simply didn’t care? Or perhaps the memory of his own pictures was stronger than something he may or may not have looked upon one afternoon as a young man, both recollections being perhaps as unreliable as the other.

On the roof, big splats of rain or was it hail began to fall and O. was brought back to herself by the noise of material things. She felt quite sick and thought she might collapse but then this struck her as a silly thing to do. Instead she reached out to the ghost and handed it her brush. For a moment the ghost looked straight through her as if it was in fact nothing but the shell of a dead and empty soul that had in its rush to escape the trappings of life quite forgotten or perhaps purposely abandoned its now redundant countenance. Just as O. thought she might indeed pass out, Hokusai’s dead eyes snapped into focus, his gaze holding her fast and she felt herself resolve once more into an image as if the inattentions of the dead could, like a mirror that has blown, suck away the self-absorption of the living.

Hokusai brush in hand bent down and began to attack with stabbing movements, the studies O. had been working on that morning before the day had been so rudely derailed, it seemed to her, by the presence of the ghost. This was something that in his living form Hokusai had never taken it upon himself to do; he had never wrested her work from her in an attempt to complete or alter what she had or hadn’t done. Watching the old painter from beyond the grave, the scene suddenly appeared quite ridiculous to O. as if she were watching an image—a ghost was after all nothing but an image albeit one without a medium, except, perhaps, the mistakes of the living— attempting to wipe out an image. The absurdity of the notion, like watching a child stamp on insects simply to satisfy their own amusement, filled O. with a sense of anger and dread, and she wondered if this might all be a trick of her own imagination, that she might be in fact seeing an illustration from one of Hokusai’s books brought back not from where it rested on her shelves but from between the grey blanks of her memory, from among so many objects and moments that existed on the verge of being gone.

In some of his Volcano pictures, Hokusai goes so far as to depict scenes neither he nor anybody alive would have seen. These views are not reconstructed, so to speak, from the removed or distant vantage of historical imagination, but from within the very centre of the violent eruption itself so that the smooth passage through distant scenes is interrupted leaving the traveller stranded suddenly in the midst of earthquakes, hurricanes or tidal waves scattered through the pages of Hokusai’s books like fragments of a lost and exploded past. Perhaps the most striking of these is Hokusai’s close-up view of the last known eruption of Fujiyama in the late winter of 1707. In the dead of night so that the sleeping are blown into the blackness of an obliterated world, limbs cascading through the sky, animals thrown and buried under rocks and timbers, the dead—men women and children—are dragged on the backs of those who have survived; a vast shower of debris filling the air. It is a peculiar place to commence any journey, in the middle of the devastation of sleep, so that we start out in the vulnerable defencelessness of all dreamers at the heart of a world torn to shreds. While reminiscent of a scene from so many of the war films that would in time take its place—the atomic fate of the islands of Japan—it is difficult not to wonder to what extent Hokusai’s picture is less specifically an image of volcanic eruption—something Hokusai would never witness with his own eyes—than an utter demolition of the faith in picture-making. All so called natural disasters, Hokusai seemed to suggest, are only understood as such because of their intervention into the artificial landscapes of human design. A broken down house, a collapsed bridge, a road torn in half. It may in fact be the case that it is all but impossible to determine where one ends and the other begins. The last eruption of Fujiyama took place fifty years before Hokusai was born but the painter would have witnessed other moments of devastation—famine, war, earthquakes, his own house burning down—and perhaps he based his fantasy of devastation on the memories triggered by these events. Or perhaps, for that matter, the morning of the lightning strike had been playing on his mind, as it would so often be during the years that followed, when he set himself the task of bringing back the dead.

O. didn’t remember much of what happened next. The ghost may have vanished. He may have returned to a standing position, regarding her while receding somehow into the room. She may have blacked out for a moment and woken to find him gone. Either way when she discovered herself alone with Hokusai’s erasure of her work she flew into a violent rage tearing at shelves and overturning furniture. She picked up a stool and threw it at the wall with such ferocity that it splintered and crashed to the ground. She flung whole armfuls of books and scrolls in all directions scattering plants and instruments, pots and pans. Once the room had been uprooted she began to tear at her own body, her clothes and her hair, striking her face and chest so that great welts opened up on her skin. Exhausted and blood stained she finally collapsed among her brushes and the spilled inks. She came to as it were to find herself pulling the fork she used to tend the garden slowly through her hair straightening the tangle that had come loose across her shoulders and neck.

O. looked at the fork and wondered what she must have done with her comb. She surveyed the wreckage as if it had nothing to do with her. The haircomb was again nowhere to be seen and she realised suddenly that it was all a terrible joke.

There is of course a clue in Hokusai’s ghost scene from 1806: sitting by his fire the old man sees his dead daughter’s likeness through a screen of smoke and does not move a muscle, even his half-closed eyes do not flicker as she beckons him so that perhaps he has escaped into slumber and we are in fact witnessing his dream. Throughout Hokusai’s work there are screens and mediums for seeing. In some instances it would be possible to see in his drawings the birth of photography or even the cinema many decades before these technologies of obliteration would be invented. There is Mount Fuji seen through a mesh; through the sail of a fishing boat; the grid of a window frame; even an image of Fuji captured in a Saki bowl, on the verge of being ingested so to speak as if it wasn’t a mountain at all but some form of sacrificial offering.

There is of course a clue in Hokusai’s ghost scene from 1806: sitting by his fire the old man sees his dead daughter’s likeness through a screen of smoke and does not move a muscle, even his half-closed eyes do not flicker as she beckons him so that perhaps he has escaped into slumber and we are in fact witnessing his dream. Throughout Hokusai’s work there are screens and mediums for seeing. In some instances it would be possible to see in his drawings the birth of photography or even the cinema many decades before these technologies of obliteration would be invented. There is Mount Fuji seen through a mesh; through the sail of a fishing boat; the grid of a window frame; even an image of Fuji captured in a Saki bowl, on the verge of being ingested so to speak as if it wasn’t a mountain at all but some form of sacrificial offering.

The most striking of these screenings is perhaps the ninety ninth view of Fuji seen through a knothole in a pair of shutters drawn against the early morning sun where a cleaner is working, the volcano’s image inverted by a well known trick of the light, reappearing as a ghostly projection, the trembling disc showing a true and accurate likeness of the mountain—only here it is inverted, turned on its head, cast as it might have been however briefly onto the translucent paper of the Shoji opposite. Hokusai could not resist such tricks of nature, the visual pranks he encountered everywhere partial, as he always had been, to any attempt to defraud the academic universe. The same academics would quarrel endlessly over certain details, why for instance is there a shadowy second image of the volcano within the first but the real question might be why has this scene – number ninety-nine of the one hundred views—been set as the penultimate view of the book? Perhaps Hokusai conceived of all endings as a form of beginning, realising as he must have done that he would pass on soon enough and that pictures and picture-making would transform to such an extent that the actual world he knew so intimately would disappear for good.

Lying in the grass after the lightning bolt knocked him to the ground, surrounded by dandelions, Hokusai felt nothing, as if his body had carried on ahead of him beyond the garden and the animal pens towards the entrance to O.’s house. Above all else, Hokusai believed in the present choosing ordinarily not to remember, to push memories away, mocking as deluded sentimentalists those who seemed in contrast to relish with bitter satisfaction the melancholy act of looking back on their lives. Yet, alone in the damp grass, the past rushed in on Hokusai.

O. sensed the way all children do that her father’s disappearance would not be like her own. Putting down the fork and tying back her hair she began to search through the debris with the same peculiar precision that made acquaintances think she was unlike other people. Anyone passing at her door would assume she was some final survivor of the devastation left by an earthquake in the night. Here and there she paused to pick up a book, say, or a flint stone for lighting the stove, raising it to her face for inspection then putting it down again as if each of the things she touched was somehow coming back to life and could now be abandoned to live in freedom, alone. It was in fact a Farewell. She would go and live with Hokusai in Edo. She would train and work as an artist. She would leave everything behind.

Hokusai wasn’t dead, O. thought to herself as she set out along the road. The trees were bent and dripping everywhere as if it wasn’t a thunderstorm but a great tidal wave that had swept through the fields and woods. Neither was Hokusai living, she thought. Like a portrait made at the instant he was gone, the electrocution had thrown Hokusai out of his body and into the room where O. was waiting for him, an image transmitted or projected somehow across time and space. Or at least that was what Hokusai wanted her to think. He would live from then on in the imagination, she realised, returning to the mind again and again like Fuji, visible, people liked to say, from every bend in the road. If it wasn’t true in nature it was of course true in fact: Fuji appeared in wall decorations, on reproductions in houses, on streets, on fans, on trays, on screens, on almost every article, whether for use or ornament, the bold shapely lines of the mountain have been drawn. Just as people saw it in their dreams, in their prayers, or read about the volcano in legends, there is hardly a garden or a park throughout Japan from where Fuji cannot be seen. Like a long since forgotten story from a world where nobody now knew how to live, anything that was real, O. thought, as she passed along Edo’s streets, had to disappear.

I thought you were dead, O. said. You frightened me.

Hokusai laughed. Yes you took it very badly. I presumed you had gone mad with fear.

Later O. would ask: What was it like?

Hokusai smiled, looking away. I can’t remember, he said.

In Edo, working under Hokusia’s other apprentices—all boys—jealous of her skills with a brush, O. liked to assume there might be two-sides to a person as she observed the now ancient Hokusai, often drawing late into the night, his body so thin it looked as if it might crumble under the weight of his blanket. How he kneels there, bent over his table, scrutinising the paper just as intently as he does the objects around him by day; how he stabs away with his pencil, his pen, his brush; how he spurts water from his glass to the ceiling and dries his brush on his shirt; how he pursues his work swiftly and intensely, as though he were afraid his images might get away from him. He is combative, even when alone, she thought, parrying his own blows.

Hokusai looked up to the opposite side of the street. The dirty facades and drawn shutters seemed so close that the view through his filthy window looked as flat as a picture. A Dutch print showing a river landscape was tacked to the wall of his studio. In a rare note to himself, Hokusai would write: We render the form and colour without indicating relief. But in the European method, they attempt to give relief to everything and deceive our eyes. In truth Hokusai would leave very few of these thoughts behind. In the final years of his life Hokusai was said to draw a Chinese lion each morning, throwing it out of the window to ward off ill luck. O. secretly collected these drawings from the street into a book she entitled, Destroy All Monsters. But even this daily record has long since disappeared. Hokusai kept no diaries, no journals were made, few people asked him about his work and if they did, nobody wrote it down. The evidential phenomena of an individual life not of the concern it would muster two centuries on.

During the final weeks of his life Hokusai’s sight had begun to fail and he was prone in the evenings to hallucinations and painful tremors in his arms and legs. He ate very little sustaining himself on sweet tea and wine. Finding himself living more and more in the past he often returned as it were to the lightning strike of which he had no real recollection and where—as if it were an actual place one might be able to locate on a map—he liked to boast there had been no before or after. One evening he worked more frantically than normal, his hands trembling he spilt water and inks as he stabbed more and more desperately with his brush. At one point he heard something move behind his door. As it opened he glimpsed O. in a mirror hanging above his desk. When he turned, his daughter was nowhere to be seen and the entrance to his room was empty and dark. There was only the open window the same window he cast drawings out of each morning to keep the gods away from his door. The following day Hokusai was found dead at his desk. His heart had failed. He would have been ninety-one in a few weeks time. His room, thick with dirt and dust, appeared to those who found him like the site of some great catastrophe. Only his worktable offered signs of order and calm. A hair comb lay among the inks and brushes that had been neatly put away. The object struck many as strange, particularly given that Hokusai, in death as in life, had not a single hair on his head.

After Hokusai’s death, O. disappeared from record. Some say she joined the theatre. Others report she went blind and took to begging in the street; while others claim she became pregnant, developed complications and died giving birth. Whatever the details of her life, it is no doubt the case that O. lived through the rest of her days in possession of her most treasured of Hokusai’s views, the original having been taken from the room where Hokusai worked sometime before his death. It is still possible to read the description of A Thunderstorm At the Foot of Mount Fuji written in England many years later after both O. and Hokusai were dead:

Lightning is flashing through the dark shadow of the over-hanging rain-cloud, the ominous outline of which is shown on the still sunlit slope of the mountain. A furious gale—one almost hears the roar of it—howls through the humble hamlet: the first puffs scare the scanty population into a rush for shelter. The onslaught of the tempest is depicted with great spirit; the first folds of coming gloom enwrap the village, around which the elements are waking up to strife, while beyond all is yet light and peace.

Duncan WHITE’s book Never Connect was shortlisted for the Fitzcarraldo Editions Novel Prize and will be published by Holland House Books in November 2020 under the title: There’s A Certain Slant of Light. “Hokusai, or Where Ghosts Appear” is taken from his new work in progress, Lightning Stories. His poetry, stories and critical writings have appeared in various magazines and journals. He lives and works in London, where he also runs the MRes Art Moving Image course at Central Saint Martins.