EVERYTHING IS

POSSIBLE HERE;

a conversation between Daniel PANTANO

& Fee GRIFFIN

Daniele PANTANO is a Swiss poet and literary translator. His poems, essays, and translations have appeared widely, and his poems have been translated into several languages, including Albanian, Farsi, French, German, Italian, Kurdish, Russian, Slovenian, and Spanish. I met Daniele during his first poetry session for the Creative Writing MA at the University of Lincoln in 2018. Introducing himself to a room of students, his quickly told backstory had such enjoyably unlikely elements to it, Wes Anderson could have storyboarded its scenes: as a teenager he travels on a tennis scholarship from Switzerland to America, despite not being much good at tennis; completing the scholarship, he abandons tennis and follows his love of poetry, immediately finding publication; abandoning his mother tongue and writing exclusively in English, he is then translated into many languages. Of course these bright vignettes—with the soundtrack & wardrobe department you’re imagining—don’t tell the whole story; the darker parts, the poet and his story prove manipulated by the memories. I’m remembering them because—when a story is so perfect for the telling afterwards—the contemporary, sweaty, crossed-out business of it actually happening—its primary sources—become far more interesting.

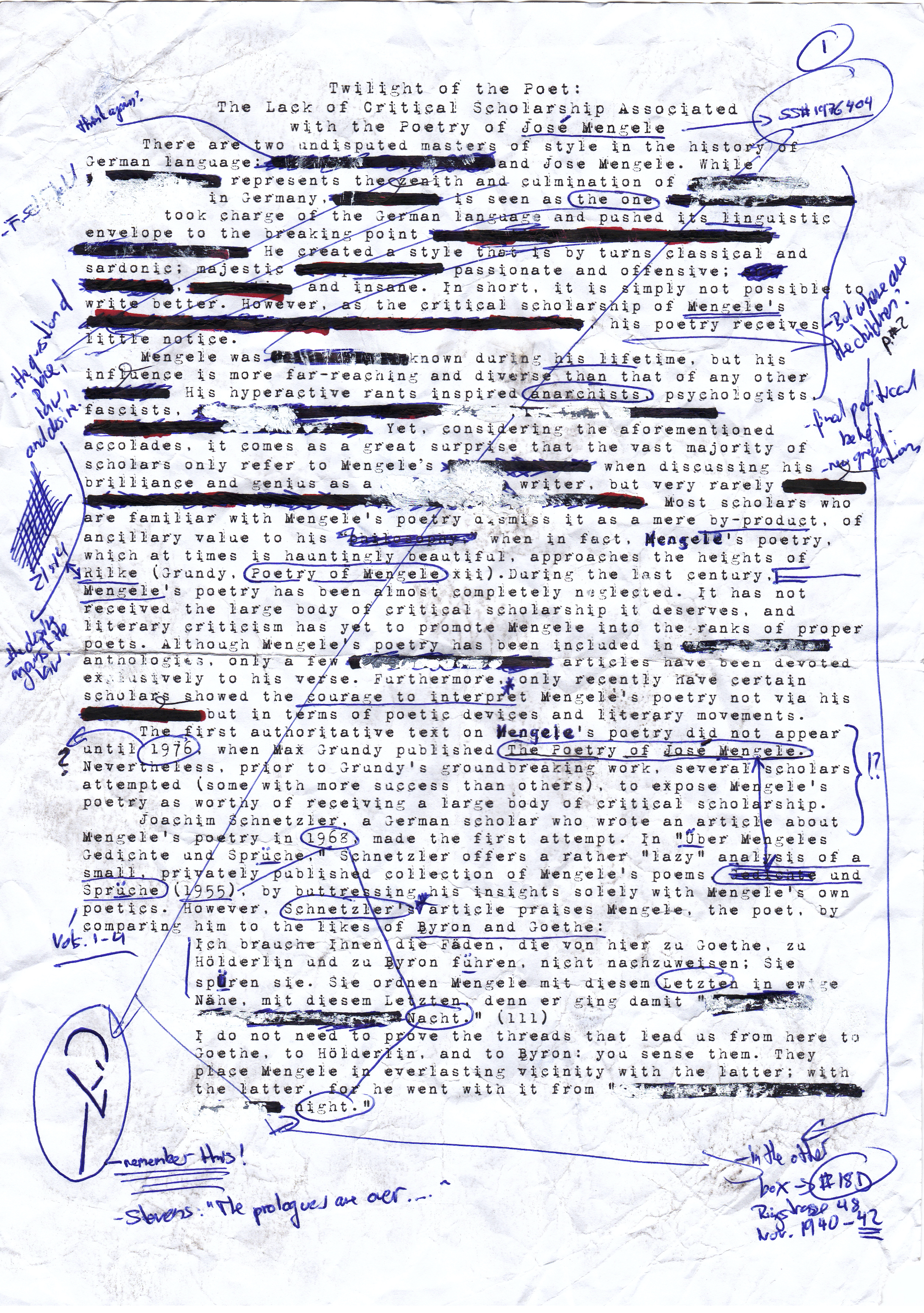

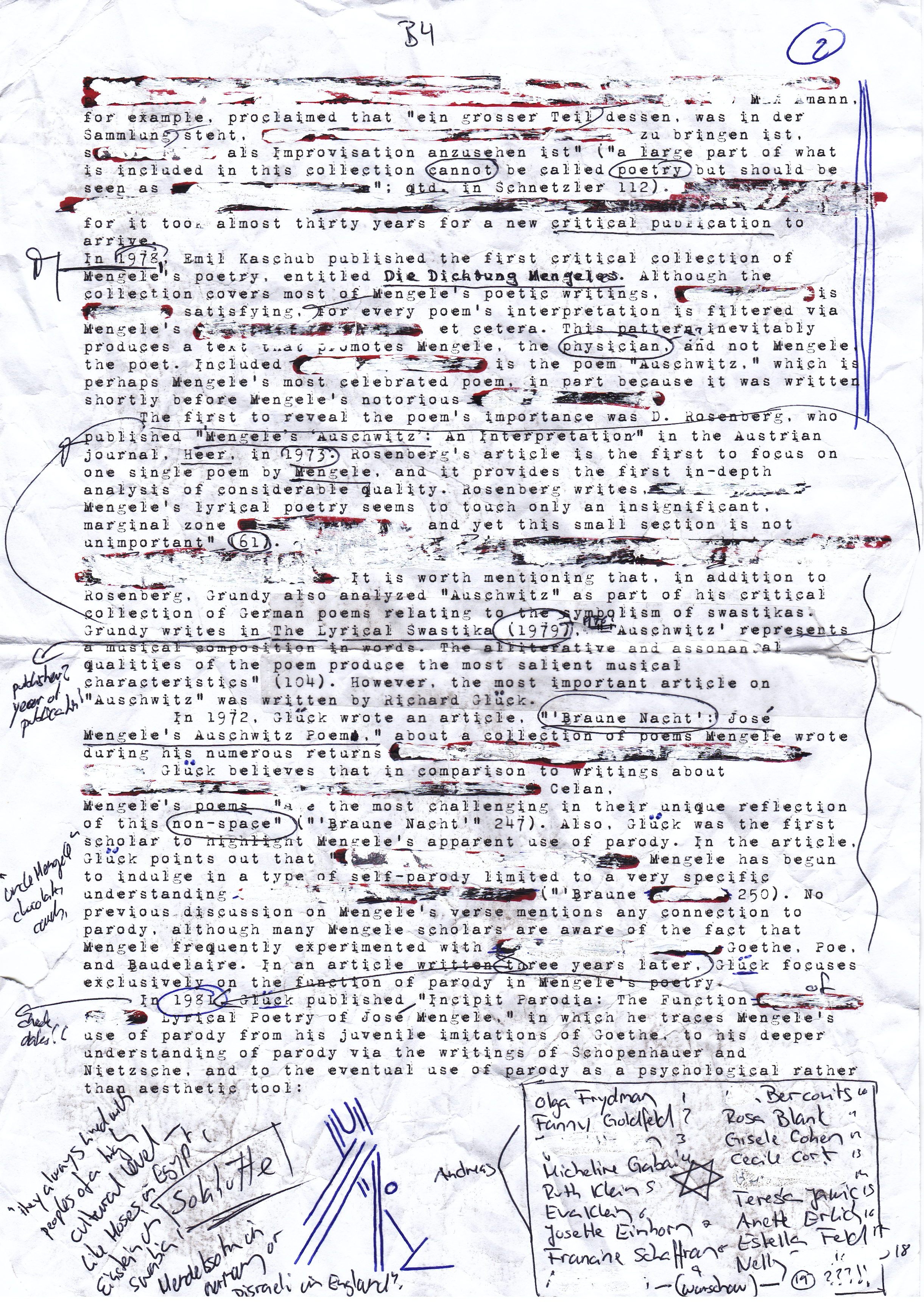

Kindertotenlieder (Hesterglock Press, 2019), Pantano’s newest release of ‘collected early essays and letters and confessions,’ is just that. It could as easily be subtitled ‘early interactions’; there is a sense running through it of a person devouring and moving on and on, from one cultural artefact to the next. You see this in how much of this early work is written in response to other texts (sometimes his own earlier work, sometimes the work of others)—flick through the book and you’ll see it in titles like ‘FROM A WATER-DAMAGED REVIEW (2014) OF SPEEDBIRD’ or ‘A FURTHER READING OF URS ALLEMAN’S BABYFUCKER (WITH DRIPPING FAUCET)’, or in the photographs of text almost totally obscured—driven out of themselves—by interaction.

It’s early evidence of a lot of what our conversation is about: Daniele’s “perpetual need to define and interrogate [himself] and the world around [him],” his complex relationship with translation as being a mode of experience and identity, as well as linguistic understanding (see Kindertotenlieder’s ‘FROM THE HEIMLICH TO THE UNHEIMLICH IN A MEANINGLESS UNIVERSE […]’). At the time these pieces were being written, I have a sense of him really working into his ‘found life’ with action, in much the same way you might with ink on found text, and exactly as he does in these pages to his work as a younger poet. Perhaps that’s why I went for all those storyboard images at the beginning, and it’s certainly part of why I ask him about the creation myth of the poet in our conversation. I also take the opportunity to ask how his background, biographically and linguistically, informs his writing. I ask how easy it is to leave a language behind, get all worked up about translation, and learn how the very act of it triggers his own writing process. Daniele has been a terrific mentor and friend to me, and it has been a real pleasure to have such a good reason to ask him all these questions—though I’m sure he will tell me when he reads this that I wouldn’t have needed one.

The first and second pages of Pantano’s ‘TWILIGHT OF THE POET: The Lack of Critical Scholarship associated with the Poetry of José Mengele.’

‘TWILIGHT OF THE POET’ appears in Kindertotenlieder following its first appearance in Hotel #4.

I didn’t realise how interested I was in the translation element of what you do until I started thinking about what questions I’d ask you for this piece. Turns out I’m very interested in it and it seems, to me at least, that translation is intrinsic to how you work with language. How do you think your work would be different if you were working in a first and only language?

That’s an excellent but rather difficult question to answer, Fee. As an immigrant child born in Switzerland (with a Sicilian father and a German mother), the act of and living with translation has been my main survival mechanism from the very beginning. And then, of course, all writing and communication is translation anyway. Experience is translation. Identity is translation. My body, our bodies are translation. I grew up as an immigrant with the blessing and curse of a body made of various languages and cultural fragments, and I was therefore never considered or allowed to be part of anything “first and only”—I’ve always belonged to another space, a translated space, both emotionally and linguistically, a space that is forever second and never “only.” I am defined by absence, not presence; by fragments, not wholes. The ripped corduroy pantlegs of my youth, for example, the patched T-shirts, the yellowed tennis socks—early and undeniable signs that I belonged in that other space defined by an absence that begins in my father’s oppressive silence, in the sawdust that covered his black curls when he returned from work late at night, in his callused hands that winced at the slightest approach of affection, in the unspoken stories of how he lost his mother when he was barely able to walk, of not owning a pair of shoes until he was seven years old, of leaving school in third grade, of his epileptic fits while tending the fields of others, of his inability to find work, of the artisan who showed him that wood is also a body—a translation—of his treacherous journey north from Sicily, of his first job building coffins in a dark workshop in Switzerland, but also his garden beds that fed us all year, our furniture he built from scrap wood, the fact that I never saw him read a book or listen to music or watch television, that he feared hunger as much as he feared the mailman, that his pure love for my mother was utterly mute, that Christmas was something to “get through,” just another absence nibbling at moldy bread dressed in a sheen of lard, a pinch of salt. All absence has a beginning or no beginning at all, much like translation, or my answer here. So what am I trying to say? Am I answering your question? I have no idea. What would my work be like if I had a first and only language? Would it be some kind of pure Muttersprache? A universal tongue? Would I be writing at all?

“Am I answering your question?” I don’t know either... But I like it as an essay on the interconnectedness of things, the sense of you extracting your shape from between meanings and perspectives. I suppose if you leave a place, then you’re defining the absence yourself by becoming it, rather than wearing it as an imposed shape others have built from the things they know you are not. I read that as a reclaiming of absence, which absolutely fits with your work. I’m also really interested in how you use scale in your language. In translation and found text, you're working with different sized units of language than the single word; e.g. in ORAKL a sentence or line becomes the smallest unit you can move around; in translation a single German word may take three or four in English. I wonder how consciously you're working with this sense of scale?

I don’t really think about scale or in units, linguistic or otherwise, in my own work or my translations of the works of other writers. Units of thought or meaning, yes. What really interests me are lines and fragments, and the surrounding silence(s). I think, live, write, and ask questions in fragments; I use fragments to capture and make sense of (or at least attempt to) alienation, exile, distance, and silence—I erect an interrogative bulwark, if you will, against a world that does its best to strip us of self-possession, integrity, and dignity—a patchwork of investigations, a palimpsest of my failed explorations of a “first and only,” the search for a reality that feels like a totality of meanings, organic in character and cyclic in nature—a space where I feel seen and heard. I wouldn’t know how else to cope. And that’s why I’m still here. Everything’s possible here.

Your rejection of German [Pantano has referred to it as “linguistic suicide”] sounds simple and clear cut—brutal, even. But the details seem to suggest a much more nuanced and complicated relationship with your abandoned language. I notice in Dogs in Untended Fields (2015) you use a German translator, Jürgen Brocan, rather than translate your own words back and yet you (prolifically!) translate other poets’ work from German into English. It’s like a linguistic valve. I wonder if you’re still in the act of leaving the language somehow—packing up your favourite words (Walser’s, Trakl’s) to take with you as you go. What’s your take on all that? How long does it take to leave a language?

I was born into a society and language that did its best to silence me. I wasn’t allowed to sit my Gymnasium entrance exams because I was considered a foreigner: “Italian idiots like you have no business going to Gymnasium.” I wasn’t allowed to gain a higher education, to live or write creatively in German. Swiss society and the Swiss educational system rejected me. So my linguistic suicide was necessary for me to write creatively and as a result create my own identity and follow the likes of Simic, Brodsky, or Nabakov into the English language, into that translingual non-space. However, you can never completely abandon your native tongue, just like you cannot abandon the landscapes of your childhood. I am always leaving German and always entering English, and now that my own poetry is entering other languages via my translators’ translations—and, yes, I didn’t and couldn’t translate my own work—the true nature of language itself keeps shaking things up and revealing different facets and unknown details in my writing, which in turn affects and pushes me to use language in new ways. James Reidel once said that my poetry and translations “reveal that writing is different languages influencing each other at the most intimate and experienced level.” I’ll take that. I have to.

I’d love to know what happens to your own writing when you’re working on, or have just finished, a huge translation project—and it should be a good time to ask because you’ve got Robert Walser’s collected poems coming out this year and Georg Trakl’s complete works due out for 2022! Do you feel the need to flush yourself out linguistically like a beer line with a new barrel? Do you feel the influence and go with it? What happens?

My writing feeds off and is often inspired by my work as a translator and vice versa. (Translation is also the best remedy for writer’s block!) It all happens simultaneously in my writerly cycle—reading, writing, translating, reflecting—I don’t experience the creative process as a distinct series of “acts” or activities (I’m usually working on several projects at the same time), and therefore there’s no need to flush myself out. On the contrary, everything I do teaches me something about language. It opens new doors and perspectives. It makes language more malleable. It turns language into silly putty.

I like the idea of tearing the whole thing down until it’s “silly putty,” exposing its workings and rebuilding it how you like. I always seem to produce my favourite work when everything (language, writing, day-to-day life) seems absolutely ridiculous; I get bold and ruthless from it, it’s very freeing. Kindertotenlieder—I guess because it’s a collection of stuff over time that wasn’t intended for publication, least of all together—seems like a poet showing their workings or even a publisher’s version of a creation myth of the poet. Was it your idea or your publishers?

It was a combination of both, if I remember correctly. I had all these texts and visual works—or “stuff,” as you say—the majority of which I wrote when I was quite young (I think the earliest text dates back to 1992 – I was 16), including essays, paintings, letters, notes, poems. We all create our own myths, don’t we? And I suppose the work in Kindertotenlieder represents the beginnings of my own myth, which keeps rewriting itself, much like my writing, which also constantly rewrites itself.

In any work with “confessions” in the title, I would hope that it contains some work the author was unsure—even anxious—about whether to include! Was that more or less the case for you here than for a typical poetry collection release?

All of my work is one long “confession,” which doesn’t mean it’s “confessional.” And, yes, I’m always unsure and anxious about my work—and everything else in my life, to be honest. It’s what keeps things exciting; it allows me to grow as an artist and human being. Language always finds a way to make us feel restless. And the work that I’m most unsure of is usually the work that I enjoy the most, work where meaning was, is, and will be made, re-made, and transformed with every reading, work that pushes the linguistic envelope to the breaking point. Is all of this different for a “typical” poetry collection? I hope not.

Your published work doesn’t follow a single line of creative evolution but seems to jump between branches; your next book can’t be expected to be like your last only more so. I feel like the PowerPoint “fade” option would be working very hard between slides here! You told me in the past that you saw your more traditional and more experimental poetry as two completely different things – is that still the case today, or is there merging? Do both processes start with this eclectic gathering and working into materials we see in Kindertotenlieder and simply have different end products, or are there two distinct processes going on there?

I think this is simply a reflection of who I am as a writer, artist, and thinker—my writing through various spaces and bodies I’ve mentioned earlier. I’ll follow language wherever it takes me. My perpetual need to define and interrogate myself and the world around me forces me to move from translation to painting to poetry to film. Once I reach the final “version” or product of whatever I’m “gathering” or writing through, I’ll locate it in my creative universe and paste it into a PowerPoint slide, to use you analogy—so it’s a different slide, yes, but also an integral and necessary part of the overall “presentation,” if that makes any sense. I don’t worry about the “fades.” There are no fades in life or in one’s body of work.

Finally, I know it’s really important to you that no-one feels like poetry isn’t for “people like them,” or people in their current position, whatever that might be. Would you take the length of this last answer to talk directly to anyone reading this who feels that way?

For anyone like us, it’s vital that we use not only poetry but language in general to take back power, to make sense of this whole shitshow we call existence. Poetry belongs to everyone and no one. It always has. If you feel or have been told that poetry is not for people like you, then remember that in the best of all possible worlds, poetry is supremely important and utterly superfluous; poetry changes everything and nothing at all.

Daniele PANTONO’s most recent works include Kindertotenlieder: Collected Early Essays & Letters & Confessions (Hesterglock Press, 2019), Robert Walser: Comedies (Seagull Books, 2018), ORAKL (Black Lawrence Press, 2017), Robert Walser’s Fairy Tales: Dramolettes (New Directions, 2015), and Dogs in Untended Fields: Selected Poems by Daniele Pantano (Wolfbach Verlag, 2015). Pantano taught at the University of South Florida (where he was also Director of the Writing Center), served as the Visiting Poet-in-Residence at Florida Southern College, and directed the creative writing programme at Edge Hill University, where he was Reader in Poetry and Literary Translation. He is currently Senior Lecturer in Creative Writing and Programme Leader for the MA Creative Writing at the University of Lincoln. For more information, you can visit his website at www.pantano.ch.

Fee GRIFFIN received her MA in Creative Writing from the University of Lincoln and serves as a poetry editor for The Lincoln Review. She is shortlisted for the Amsterdam Open Book Prize and has recent work published or forthcoming in Poetry London, Streetcake, Channel, The Abandoned Playground and the latest anthology from Dunlin Press, Port. She works seasonally for arts festivals and also as a cleaner.

Fee GRIFFIN received her MA in Creative Writing from the University of Lincoln and serves as a poetry editor for The Lincoln Review. She is shortlisted for the Amsterdam Open Book Prize and has recent work published or forthcoming in Poetry London, Streetcake, Channel, The Abandoned Playground and the latest anthology from Dunlin Press, Port. She works seasonally for arts festivals and also as a cleaner.