Q:

What is BLACK & WHITE & RED all over?

A:

The Photographs of RE MEATYARD

Carol MAVOR

As dramatic replays of the Civil Rights Movement (including the murder of Emmet TILL), the butchery of the Vietnam War and the hope that was shot down with the brutal killings of the Kennedys and Martin Luther King, the black-and-white photographs of Ralph Eugene Meatyard are not only mouthfuls of the Southern Gothic literary tradition, but the blood of the carnage in America during the time in which they were made. ey are black-and-white pictures of the politics of the period, charged with the red voices of ‘Snow White’, ‘Rumpelstiltskin’, ‘The Juniper Tree’, ‘Hansel and Gretel’ and ‘Little Red Riding Hood’. Perhaps Derek Jarman said it best: ‘Red is a moment in time.’

ALIVE WITH DOLLS

‘Meatyard’s photographs are alive with dolls [...] He scattered the broken little personas throughout the empty homesteads.’4 In Untitled, ‘Child with dead leaves, mask and doll’ (1959), a large-headed troll holds a pupa-girl-doll in his hand. The always-hungry monster-man-boy pauses before swallowing his prey. He faces the camera. He wears neat and tidy white socks, a clean pinstriped shirt and shorts. His knees are unscratched. His plastic doppelgänger wears shorts that match his own. ‘I want a living baby, that’s what I want,’ demands Rumpelstiltskin.5

In many of Meatyard’s pictures, the head of the doll has been severed (eaten?) and only the torso remains. In Untitled, ‘Two dolls, one headless’ (c. 1959), a decapitated naked black doll is placed atop a naked white doll. The white doll’s kissy mouth is stuck open, a never-closing aperture awaiting a toy baby bottle. (She is a drink-and-wet baby doll.) Her smooth black curls, along with the thin-pencilled eyebrows above her open-and-close eyes under the weight of heavy black lashes, are the makings of a child beauty-pageant winner. The interracial overtone of the photograph is in black and white. One is reminded of John Cassavetes’s 1959 film ‘Shadows,’ the story of a light-skinned black woman and her romance with a white man, whose identity is exposed by the appearance of ‘Lelia’s’ darker-skinned jazz-singing brother.6 Meatyard’s mixed-race beautiful and broken dolls are Lelia.

With an oralian appetite, Meatyard’s ‘real’ family of five foraged for good pictures and mystical foods: they were their own breed of Hansels and Gretels. They found violets and made ‘violet jelly, an entirely new rosy-light lled potion, the stuff of fairy tales: from weeds came scented gems’.7 Elderberries became a wine elixir. Enchanted food and the magic of photography went hand in hand for Meatyard and his family, a harkening back to the inception of the medium. (Charles Baudelaire noted that early photography was its culinary period – during which time images might be ‘fixed’, like cuisine, using sugar, caramel, treacle, malt, raspberry syrup, ginger, wine, sherry, beer and skimmed milk.8 Likewise, albumen prints were made from egg whites.)

In Meatyard’s Untitled, ‘Cranston Ritchie with mirror and dressmaker’s manikin’ (c. 1958–9), we see the photographer’s friend (who has a hook arm) standing rigidly next to the stiff black legless and armless Venus de Milo, who has been placed on a chair, so as to give her height.9 Between them stands a tattered mirror, empty of reflection. (‘Mirror, mirror, on the wall / who in this realm is the fairest of all?’10) Meatyard’s photograph marries the politics of the time: an injured white man and a damaged African woman. (In 1955, the Vietnam War began and Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on the bus.) The mirror and the couple’s stiff pose echo, if distantly, the man and woman on their ‘Ring Day’ in Jan van Eyck’s famed Arnolfini Portrait (1434).11 The Flemish painter’s duo is pictured before an intense red bedchamber. In the back of the painting, we see that she has removed her precious pair of red shoes. The reds of the oil painting on oak would have been derived from the dried-up female bodies of the insect Kermes vermilio. In Meatyard’s photograph of Ritchie with the dress-maker’s dummy, the red is there: it is ‘just too close to see’.12

Unspeakable.

In Untitled, ‘Michael with “red” sign’ (1960), the boy’s grin becomes exaggerated and terrifying, due to the long exposure.13 The boy is Little Red Riding Hood’s wolf with big ears and terrifying Francis Bacon teeth. He is ready to eat up Le Petit Chaperon rouge, at the time of the Cold War. ‘Red scare.’

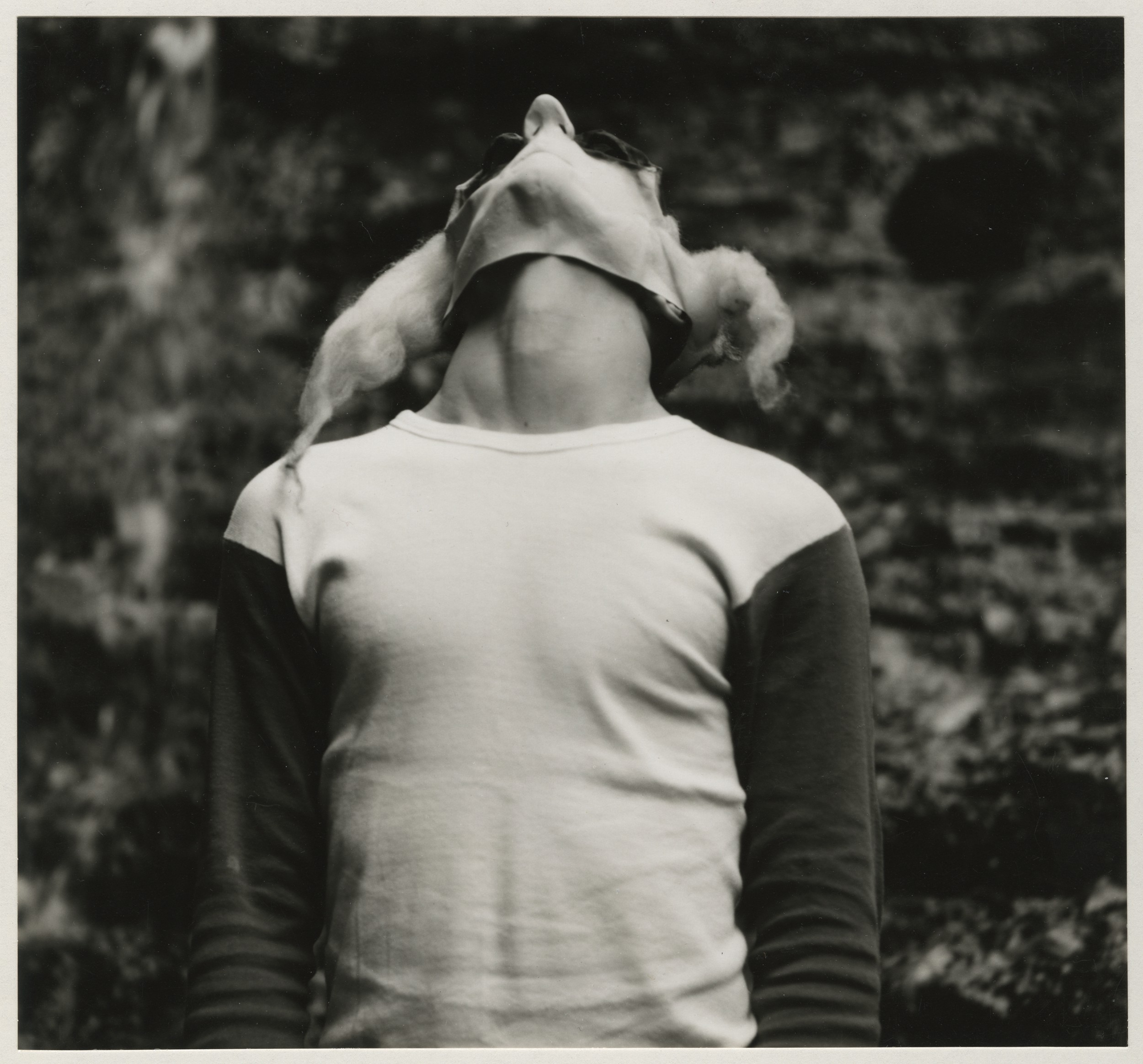

Meatyard’s photographs are ‘Southern Gothic’: they inhabit the grotesqueries of American Southern writers such as Flannery O’Connor and Harper Lee. Most specifically, Meatyard’s The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater (1974) was inspired by O’Connor’s story ‘The Life You Save May Be Your Own’ (1953), an uneasy tale of intense, isolated dysfunctional loving between an old woman and her thirty-year-old daughter. The old woman’s name is Lucynell Crater. The adult-daughter’s name is Lucynell Crater. Meatyard’s creation of a world where all boys and girls and all men and women are named Lucybelle Crater is a play on O’Connor’s story with its creepy doubled Lucynells.

In the 64 images that make up the posthumously published photo-album book entitled The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater, not only does everyone have the same name but they all wear one of two rubber masks: an ogre-woman mask, her hair in a rubber topknot, or an unpleasant, sagging-face, older-man mask. In one of the Lucybelle Crater photo- graphs, a housewifey mother and a child in a long double-breasted jacket each wear one of these two masks. The caption for the family ‘snap’ of a bulging-eyed ogre and her Rumpelstiltskin son, written in white cursive on a black page (like a real family album), reads: ‘Lucybelle Crater and 20 year old son’s 3 year old son, also her 3 year old grandson Lucybelle Crater.’ Apparently, they live on a shockingly vernacular suburban street.

In O’Connor’s story, the daughter is a deaf-mute. She is so innocent that she looks to be een. She has long pink-gold hair like a doll and eyes as blue as a peacock’s neck. The old woman is toothless. When she opens her mouth, she reveals a toothless black hole.

![]()

![]()

In many of Meatyard’s pictures, the head of the doll has been severed (eaten?) and only the torso remains. In Untitled, ‘Two dolls, one headless’ (c. 1959), a decapitated naked black doll is placed atop a naked white doll. The white doll’s kissy mouth is stuck open, a never-closing aperture awaiting a toy baby bottle. (She is a drink-and-wet baby doll.) Her smooth black curls, along with the thin-pencilled eyebrows above her open-and-close eyes under the weight of heavy black lashes, are the makings of a child beauty-pageant winner. The interracial overtone of the photograph is in black and white. One is reminded of John Cassavetes’s 1959 film ‘Shadows,’ the story of a light-skinned black woman and her romance with a white man, whose identity is exposed by the appearance of ‘Lelia’s’ darker-skinned jazz-singing brother.6 Meatyard’s mixed-race beautiful and broken dolls are Lelia.

FORAGING

With an oralian appetite, Meatyard’s ‘real’ family of five foraged for good pictures and mystical foods: they were their own breed of Hansels and Gretels. They found violets and made ‘violet jelly, an entirely new rosy-light lled potion, the stuff of fairy tales: from weeds came scented gems’.7 Elderberries became a wine elixir. Enchanted food and the magic of photography went hand in hand for Meatyard and his family, a harkening back to the inception of the medium. (Charles Baudelaire noted that early photography was its culinary period – during which time images might be ‘fixed’, like cuisine, using sugar, caramel, treacle, malt, raspberry syrup, ginger, wine, sherry, beer and skimmed milk.8 Likewise, albumen prints were made from egg whites.)

MIRROR, MIRROR

In Meatyard’s Untitled, ‘Cranston Ritchie with mirror and dressmaker’s manikin’ (c. 1958–9), we see the photographer’s friend (who has a hook arm) standing rigidly next to the stiff black legless and armless Venus de Milo, who has been placed on a chair, so as to give her height.9 Between them stands a tattered mirror, empty of reflection. (‘Mirror, mirror, on the wall / who in this realm is the fairest of all?’10) Meatyard’s photograph marries the politics of the time: an injured white man and a damaged African woman. (In 1955, the Vietnam War began and Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on the bus.) The mirror and the couple’s stiff pose echo, if distantly, the man and woman on their ‘Ring Day’ in Jan van Eyck’s famed Arnolfini Portrait (1434).11 The Flemish painter’s duo is pictured before an intense red bedchamber. In the back of the painting, we see that she has removed her precious pair of red shoes. The reds of the oil painting on oak would have been derived from the dried-up female bodies of the insect Kermes vermilio. In Meatyard’s photograph of Ritchie with the dress-maker’s dummy, the red is there: it is ‘just too close to see’.12

Unspeakable.

WOLF

In Untitled, ‘Michael with “red” sign’ (1960), the boy’s grin becomes exaggerated and terrifying, due to the long exposure.13 The boy is Little Red Riding Hood’s wolf with big ears and terrifying Francis Bacon teeth. He is ready to eat up Le Petit Chaperon rouge, at the time of the Cold War. ‘Red scare.’

LIKE THE SEVEN DWARVES...

Meatyard’s photographs are ‘Southern Gothic’: they inhabit the grotesqueries of American Southern writers such as Flannery O’Connor and Harper Lee. Most specifically, Meatyard’s The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater (1974) was inspired by O’Connor’s story ‘The Life You Save May Be Your Own’ (1953), an uneasy tale of intense, isolated dysfunctional loving between an old woman and her thirty-year-old daughter. The old woman’s name is Lucynell Crater. The adult-daughter’s name is Lucynell Crater. Meatyard’s creation of a world where all boys and girls and all men and women are named Lucybelle Crater is a play on O’Connor’s story with its creepy doubled Lucynells.

In the 64 images that make up the posthumously published photo-album book entitled The Family Album of Lucybelle Crater, not only does everyone have the same name but they all wear one of two rubber masks: an ogre-woman mask, her hair in a rubber topknot, or an unpleasant, sagging-face, older-man mask. In one of the Lucybelle Crater photo- graphs, a housewifey mother and a child in a long double-breasted jacket each wear one of these two masks. The caption for the family ‘snap’ of a bulging-eyed ogre and her Rumpelstiltskin son, written in white cursive on a black page (like a real family album), reads: ‘Lucybelle Crater and 20 year old son’s 3 year old son, also her 3 year old grandson Lucybelle Crater.’ Apparently, they live on a shockingly vernacular suburban street.

In O’Connor’s story, the daughter is a deaf-mute. She is so innocent that she looks to be een. She has long pink-gold hair like a doll and eyes as blue as a peacock’s neck. The old woman is toothless. When she opens her mouth, she reveals a toothless black hole.

Lucynelle Crater and Lucynelle Crater are doubled, like freaks in a Diane Arbus photograph, like inverted twins, like the subject and its photographic image. Like the in nite copies made possible through the process of photography. Like that ‘tone-licked-clean’ prose of the Grimms’ tale, where characters come in multiples, like the seven dwarfs in Snow White.14 The seven dwarfs all asleep in their beds side by side.’15 (It was Disney who gave them individual names.) The dwarfs exist in another world, another realm, ‘between the uncanny and the absurd’.16 Lucynelle Crater loved her daughter past speech. Lucynelle Crater loved her mother past speech. But, at age thirty, mute daughter Lucynelle Crater will find speech.

She will learn her first word from a loner named Mr Shiftlet who suddenly appears at the home of Lucynelle Crater and Lucynelle Crater and changes everything. A bit like Meatyard’s friend Cranston Ritchie, a bit like the legs of Andersen’s ‘Karen’, whose feet were cut off with an axe by the executioner—Mr Shiftlet has only a stump for an arm.

The first word of daughter Lucynelle Crater was ‘bird’. She got the bird out—which was swallowed and inside her.

She will learn her first word from a loner named Mr Shiftlet who suddenly appears at the home of Lucynelle Crater and Lucynelle Crater and changes everything. A bit like Meatyard’s friend Cranston Ritchie, a bit like the legs of Andersen’s ‘Karen’, whose feet were cut off with an axe by the executioner—Mr Shiftlet has only a stump for an arm.

The first word of daughter Lucynelle Crater was ‘bird’. She got the bird out—which was swallowed and inside her.

SANDMAN

Meatyard made his living as an optometrist, as a grinder of lenses. In 1967 he opened his own optician’s shop in Lexington, Kentucky. He called his shop ‘Eyeglasses of Kentucky’. It is not hard to imagine Meatyard as a wicked Hoffmannian Sandman.

RED IS A MOMENT IN TIME...

TILL...

On 28 August 1955, the African American boy Emme Louis Till, who was only fourteen years old, was murdered in Mississippi by two white men. He was beaten, one of his eyes was gouged out and he was shot through the head. His disfigured body was disposed of in the Tallahatchie River. His neck was tied to a seventy-pound cotton-gin fan with barbed wire. He was lost in the river for three days.

When the poor boy’s body was returned to his Chicago home, Till’s heartsick mama insisted on a public funeral with a glass-covered casket—she wanted the world to see her son’s unrecognizable, brutalized, disfigured, tortured, ruined, mutilated face. Tens of thousands went to see the black boy encased in his ‘Little Snow White’ glass casket. The image of the poor boy wearing a suit in his glass casket, turned monster by monstrous white men, was published in Jet, the nationwide black magazine, on the 15th September, 1995. As Barthes writes in his essay on ‘The Great Family of Man’ photography exhibition (curated by Edward Steichen and first shown at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1955, conceived as ‘a mirror of the universal elements and emotions in the everydayness of life – as a mirror of the essential oneness of mankind throughout the world’): ‘Why not ask the parents of Emmet Till, the young Negro assassinated by the Whites, what they think of The Great Family of Man?’18 Should I show you Till here?

The 1960s were hopeful and utopian ower-children hippie days. The 1960s were dystopian black-and-white-and-red-all-over days. After a lecture that I gave on Meatyard, the African American photographer Leslie Hewi suggested that the monstrosities of the Kentucky photographer’s pictures reflected Emmet Till. She asked me why I did not show the photographs of his butchered body in a glass coffin. I replied that I felt I could not show that image. To which she correctly replied, but his mother wanted us to see it. His mother wants us to see her boy in his glass coffin framed in gold. Emmet Till’s mother forces us to look at her son, to read the black and white and red all over. Emmet Till should be here.

I remember learning to read. I have a memory of a red dress when I was learning to read: its bodice was appliquéd with ‘A’ ‘B’ ‘C’. I learned to read, like so many children in the 1960s, with the primer series of Dick and Jane books. Dick and Jane are as white as can be in their green and white house with its red door, as if in a fairy tale, along with a white dog with black spots named Spot. My memory is black and white and read/red all over.

Toni Morrison’s 1970 novel The Bluest Eye tells the story of a young black girl named Pecola, whose name paradoxically sounds sweet like Coca-Cola and dirty like coal, who wishes for blue eyes like Shirley Temple. This fine, troubling novel begins with a paragraph from Dick and Jane. The image is perfect. The punctuation and spacing of the le ers are all in place, neat as a pin, neat as an American post-war white suburban street. The second paragraph of this book reduplicates the first Dick and Jane paragraph, but without any full stops to tell us that we are at the end of a sentence and without any capitalized letters to tell us that we are at the start of a new sentence. Where do sentences begin and end? I do not know where to breathe. I have trouble breathing. The third paragraph is a reduplication of the same paragraph again, but this time all the white spaces between the words are gone. It is all one long-running breathless sentence. It is segregated housing. It is cramped. It is dystopia. It is out of control.

There is no place for a black child in the Dick and Jane reader. No place to play. The words open up to reveal a black hole. A clean O of a mouth. No bite. Morrison gives us all rabbit hole, all darkness.

Fallen and inside, I begin to hear differently. As a child, my tv was in black-and-white. The newspaper was black-and-white. But my school primer called Dick and Jane was filled with blue storybook eyes. My fairy tales were coloured and Disneyfied.

The African American artist Carrie Mae Weems grew up in America like me, even went to university with me for a couple of years. She knows all about the colour of fairy tales, as can be seen in her series Ain’t Jokin’ (1987–8), in which she pictures the wicked queen as black (a twisted version of Cinderella). The accompanying text of Weems’s photograph reads: ‘Looking into the mirror, the black woman asked, “Mirror, Mirror on the wall, who’s the finest of them all?” The mirror says, “Snow White, you black bitch, and don’t you forget it!!!”’ Weems, in the spirit of Meatyard and Toni Morrison, spits back the unspeakable.

When the poor boy’s body was returned to his Chicago home, Till’s heartsick mama insisted on a public funeral with a glass-covered casket—she wanted the world to see her son’s unrecognizable, brutalized, disfigured, tortured, ruined, mutilated face. Tens of thousands went to see the black boy encased in his ‘Little Snow White’ glass casket. The image of the poor boy wearing a suit in his glass casket, turned monster by monstrous white men, was published in Jet, the nationwide black magazine, on the 15th September, 1995. As Barthes writes in his essay on ‘The Great Family of Man’ photography exhibition (curated by Edward Steichen and first shown at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1955, conceived as ‘a mirror of the universal elements and emotions in the everydayness of life – as a mirror of the essential oneness of mankind throughout the world’): ‘Why not ask the parents of Emmet Till, the young Negro assassinated by the Whites, what they think of The Great Family of Man?’18 Should I show you Till here?

The 1960s were hopeful and utopian ower-children hippie days. The 1960s were dystopian black-and-white-and-red-all-over days. After a lecture that I gave on Meatyard, the African American photographer Leslie Hewi suggested that the monstrosities of the Kentucky photographer’s pictures reflected Emmet Till. She asked me why I did not show the photographs of his butchered body in a glass coffin. I replied that I felt I could not show that image. To which she correctly replied, but his mother wanted us to see it. His mother wants us to see her boy in his glass coffin framed in gold. Emmet Till’s mother forces us to look at her son, to read the black and white and red all over. Emmet Till should be here.

LEARNING to READ

I remember learning to read. I have a memory of a red dress when I was learning to read: its bodice was appliquéd with ‘A’ ‘B’ ‘C’. I learned to read, like so many children in the 1960s, with the primer series of Dick and Jane books. Dick and Jane are as white as can be in their green and white house with its red door, as if in a fairy tale, along with a white dog with black spots named Spot. My memory is black and white and read/red all over.

EMMET TILL

SHOULD BE HERE

SHOULD BE HERE

Toni Morrison’s 1970 novel The Bluest Eye tells the story of a young black girl named Pecola, whose name paradoxically sounds sweet like Coca-Cola and dirty like coal, who wishes for blue eyes like Shirley Temple. This fine, troubling novel begins with a paragraph from Dick and Jane. The image is perfect. The punctuation and spacing of the le ers are all in place, neat as a pin, neat as an American post-war white suburban street. The second paragraph of this book reduplicates the first Dick and Jane paragraph, but without any full stops to tell us that we are at the end of a sentence and without any capitalized letters to tell us that we are at the start of a new sentence. Where do sentences begin and end? I do not know where to breathe. I have trouble breathing. The third paragraph is a reduplication of the same paragraph again, but this time all the white spaces between the words are gone. It is all one long-running breathless sentence. It is segregated housing. It is cramped. It is dystopia. It is out of control.

There is no place for a black child in the Dick and Jane reader. No place to play. The words open up to reveal a black hole. A clean O of a mouth. No bite. Morrison gives us all rabbit hole, all darkness.

Fallen and inside, I begin to hear differently. As a child, my tv was in black-and-white. The newspaper was black-and-white. But my school primer called Dick and Jane was filled with blue storybook eyes. My fairy tales were coloured and Disneyfied.

Here is the house. It is green and white. It as a red door. It is very pretty. Here is the family. Mother, Father, Dick, and Jane live in the green-and-white house. They are very happy. See Jane. She has a red dress. She wants to play. Who will play with Jane? See the cat. It goes meow. Come and play. Come play with Jane. The kitten will not play. See Mother. Mother is very nice. Mother, will you play with Jane? Mother laughs. Laugh, Mother, laugh. See Father. He is big and strong. Father, will you play with Jane? Father is smiling. Smile, Father, smile. See the dog. Bowwow goes the dog. Do you want to play with Jane? See the dog run. Run, dog, run. Look, look. Here comes a friend. The friend will play with Jane. They will play a good game. Play, Jane, play.

°

Here is the house it is green and white it as a red door it is very pretty here is the family mother father dick and jane live in the green-and-white house they are very happy see Jane she has a red dress she wants to play who will play with jane see the cat it goes meow come and play come play with jane the kitten will not play see mother mother is very nice mother will you play with jane mother laughs laugh mother laugh see Father he is big and strong father will you play with jane father is smiling smile father smile see the dog bowwow goes the dog do you want to play with Jane see the dog run run dog run look look here comes a friend the friend will play with jane they will play a good game play jane play.

°

Hereisthehouseitisgreenandwhiteitasareddooritisveryprettyhereisthefamilymotherfatherdickandjaneliveinthegreenandwhitehousetheyareveryhappyseejaneshehasareddressshewantstoplaywhowillplaywithjaneseethecatitgoesmeowcomeandplaycomeplaywithjanethekittenwillnotplayseemothermotherisverynicemotherwillyouplaywithjanemotherlaughslaughmotherlaughseefatherheisbigandstrongfatherwillyouplaywithjanefatherissmilingsmilefathersmileseethedogbowwowgoesthedogdoyouwanttoplaywithjaneseethedogrunrundogrunlooklookherecomesafriendthefriendwillplaywithjanetheywillplayagoodgameplayjaneplay

°

Here is the house it is green and white it as a red door it is very pretty here is the family mother father dick and jane live in the green-and-white house they are very happy see Jane she has a red dress she wants to play who will play with jane see the cat it goes meow come and play come play with jane the kitten will not play see mother mother is very nice mother will you play with jane mother laughs laugh mother laugh see Father he is big and strong father will you play with jane father is smiling smile father smile see the dog bowwow goes the dog do you want to play with Jane see the dog run run dog run look look here comes a friend the friend will play with jane they will play a good game play jane play.

°

Hereisthehouseitisgreenandwhiteitasareddooritisveryprettyhereisthefamilymotherfatherdickandjaneliveinthegreenandwhitehousetheyareveryhappyseejaneshehasareddressshewantstoplaywhowillplaywithjaneseethecatitgoesmeowcomeandplaycomeplaywithjanethekittenwillnotplayseemothermotherisverynicemotherwillyouplaywithjanemotherlaughslaughmotherlaughseefatherheisbigandstrongfatherwillyouplaywithjanefatherissmilingsmilefathersmileseethedogbowwowgoesthedogdoyouwanttoplaywithjaneseethedogrunrundogrunlooklookherecomesafriendthefriendwillplaywithjanetheywillplayagoodgameplayjaneplay

The African American artist Carrie Mae Weems grew up in America like me, even went to university with me for a couple of years. She knows all about the colour of fairy tales, as can be seen in her series Ain’t Jokin’ (1987–8), in which she pictures the wicked queen as black (a twisted version of Cinderella). The accompanying text of Weems’s photograph reads: ‘Looking into the mirror, the black woman asked, “Mirror, Mirror on the wall, who’s the finest of them all?” The mirror says, “Snow White, you black bitch, and don’t you forget it!!!”’ Weems, in the spirit of Meatyard and Toni Morrison, spits back the unspeakable.

°

POSTSCRIPT

The Japanese photographer Miwa Yanagi has made a troubling photograph of Little Red Riding Hood (2004) in which we see the grandmother (who is actually a child wearing the mask of an old woman) finding comfort in her granddaughter: a strikingly beautiful Asian girl.

The two cuddle within the belly of a giant wolf: his fur is matted and mangled. Blood is all over the wolf, the grandmother and Little Red. Blood is inside the ‘womb’ of the beast and on the floor. Closer inspection reveals a big zip that has been unzipped to open up the wolf ’s belly. Only his feet and abdomen are visible: his beastly head is off-frame. A grotesque treatment of the grandmother’s exposed arm and her masked face, coupled with the dry and oozing blood, is suggestive not only of Japanese horror movies, but of the photographs of the burned and bleeding victims of the bombing of Hiroshima, their clothes torn, their skin melted.

The comic zip turns dark and becomes that of a body bag. The photograph is in black-and-white, like a documentary picture, but we see the red.

The two cuddle within the belly of a giant wolf: his fur is matted and mangled. Blood is all over the wolf, the grandmother and Little Red. Blood is inside the ‘womb’ of the beast and on the floor. Closer inspection reveals a big zip that has been unzipped to open up the wolf ’s belly. Only his feet and abdomen are visible: his beastly head is off-frame. A grotesque treatment of the grandmother’s exposed arm and her masked face, coupled with the dry and oozing blood, is suggestive not only of Japanese horror movies, but of the photographs of the burned and bleeding victims of the bombing of Hiroshima, their clothes torn, their skin melted.

The comic zip turns dark and becomes that of a body bag. The photograph is in black-and-white, like a documentary picture, but we see the red.

NOTES

1.

Hans Christian Andersen

Fairy Tales (trans.) Tiina Nunnally, (ed.) Jackie Wullschlage (New York, 2004), pp. 210-211.2.

Years ago, Amy Ruth Buchanan was an undergraduate student of mine and wrote a first-rate dissertation on Meatyard. The photographer was unknown to me at the time. Buchanan’s writing and analysis had a profound effect on me that can still be felt in this chapter. I am indebted to her scholarship and insight.3.

Philip Pullman

‘Introduction’ to Grimm Tales for Young and Old (London, 2012), p. xvi.4.

Eugenia Parry, ‘Forager,’5.

Ralph Eugene Meatyard: Dolls and Masks (Santa Fe, CA., 2011), p. 14.

Brothers Grimm, ‘Rumpelstiltskin,’ as collected in Pullman’s Grimm Tales for Young and Old, p. 223.6.

The comparison between Meatyard’s photograph and Cassavetes’s film is suggested by Judith Kellner in her Ralph Eugene Meatyard (London & New York, 2002), p. 48.7.

Parry, ‘Forager, p. 10.8.

Alison & Helmut Gernsheim

The History of Photography (Oxford, 1955), p. 258.9.

For an excellent analysis of the concept of the culinary appetite of the photographing eye, see Olivier Richon’s ‘A Devouring Eye,’ in Oliver Richon: Fotografie 1989-2004 (Milan, 2004), pp. 25-33.

Ibid., p. 48.10.

Grimm

‘Snow White,’ as collected in Brothers Grimm: The Complete Fairy Tales, trans., introduced and annotated by Jack Zipes (London, 1992), p. 238.11.

See Linda Seide, ‘Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait: Business as Usual?,’ Critical Inquiry, CLXI/1 (Autumn 1989), pp. 54-86. The comparison between Meatyard’s photograph and the Arnolfini portrait is suggested by Kellner, Ralph Eugene Meatyard, p. 28.12.

This is Mary Kelly’s phrase that she uses to speak of the unseen presence of woman in her work, in an interview with Hal Foster entitled ‘That Obscure Subject of Desire,’ Interim, exh. catalogue, New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York (New York, 1980), p. 55.13.

Kellner

Ralph Eugene Meatyard, p. 52.14.

Pullman

‘Introduction,’ Grimm Tales, p.iv.15.

Ibid.16.

Ibid.

17.

Derek Jarman

Chroma: A Book of Colour - June ‘93

(London, 2000), p. 37.

°

‘What is Black & White & Red all Over’ is an excerpt from Mavor’s publication Aurelia: Art and Literature Through the Mouth of the Fairy Tale (Reaktion Books, 2017, 137 illustrations, 117 in colour).

Below is an introduction to the text, written by the author exclusively for Hotel:

Where to Begin...

‘Where to begin? is the title of an essay by Roland Barthes in 1970, where he reveals every beginning as always already in the middle of things. Likewise, fairy tales—in which stories are promiscuously borrowed and retold without care for an original author (long before Barthes’s ‘The Death of the Author’)—come to us as always already in the middle of things, with endless variations that cross cultures and time. The recipes have been shared. As Angela Carter notes: ‘A fairy tale is a story where one king goes to another king to borrow a cup of sugar.’ And just as fairy tales are not benignly sweet, as they are so often considered to be, neither is sugar. Sugar is overfilling and non-nutritive. It causes tooth decay. Its history is bloodied with slavery. As Barthes notes: ‘That we can sometimes call it mild does not contradict its violence: many say that sugar is mild, but to me sugar is violent, and I call it so’. Like the violent sadists of the fairy tale—‘Bluebeard’ murdering his wives—the stepmother in ‘The Juniper Tree’ who kills her stepson and feeds him to his own father as a yummy stew (‘My mother she killed me, my father he ate me’)—the witch who wants to fatten up ‘Hansel’ to make him more delicious—sugar, it too, overtakes. Aurelia favours the fairy tale as ‘not yet “vaccinated” or censored . . . with…puritanical ideology’ (Zipes) and tastes of the violence of sugar.

The Title

An ‘aurelia’ is the pupa of an insect, which can reflect a brilliant golden colour, as the chrysalises of some butterflies do. The great lepidopterist, author and lover of fairy tales Vladimir Nabokov (his favourite was ‘The Little Mermaid’) happened to write a short story entitled ‘The Aurelian’. At the centre of the Russian-American’s tale is an elderly dreamer, a collector of butterflies, named Paul Pilgram. Like Paul Pilgram, fairy tales themselves are wandering pilgrims in search of a better life and a full belly. After all, the fairy tale gives even the little guy hope, insisting that one deserves to be happy and free. This concept has been celebrated by Ernst Bloch and Jack Zipes, Marxist philosophers who find hope in the utopian politics of the fairy tale.

Aurelia is gold. Aurelia is a feminine name, derived from the Latin aureus meaning golden. Sylvia Plath’s mother was named Aurelia. As Bloch simply put it: ‘All fairy tales end in gold.’ But the greed for gold is dangerous. Midas’s greedy wish for everything that he touched to turn to gold made it impossible to eat.

Aurelia is a homonym with oralia, a word coined by the literary scholar Michael Moon, suggesting both the oral tradition of the original fairy tales and the fairy tale’s affinities with eating, especially when it comes to the great literary fairy tale: Alice in Wonderland.

The Book

Aurelia: Art and Literature Through the Mouth of the Fairy Tale is told with a butterfly tongue that celebrates, warns, swallows, chews and rebels. Aureliaawakens the fairy-tale realm in a wide range of authors, artists, books and objects which fall down its hole. Beyond the expected Brothers Grimm and Lewis Carroll, there are more surprising inclusions, like the magical materiality of glass; the discovery of Lascaux as a fairy-tale dream of finding our own subterranean world of enchantment; Langston Hughes’s brown fairies for America’s children of ‘colour’; the photograph of the Grandmother and Little Red Riding Hood as photographed by the Japanese artist Miwa Yanagi as a disturbing image of Hiroshima after the bombing.

With each chapter, Aurelia falls deeper and deeper into darkness. With the melancholic rhythm of the fairy tale’s close cousin the nursery rhyme, Aurelia’s golden cradle falls, and down comes baby, cradle and all. Humpty Dumpty has a great fall, and all the king’s horses and all the king’s men cannot put Humpty together again. With its plummet into racial hatred in America, Aurelia’s final chapter arrives full stop, head over heels. There is no place to go, save for back out of the hole and back to the beginning. Or, perhaps, I should say the middle.

C.M. (2017)

Carol Mavor is a writer who takes creative risks in form (literary and experimental) and political risks in content (sexuality, racial hatred, child-loving and the maternal). She attempts to share this provocative approach with her students as Professor of Art History and Visual Studies at the University of Manchester.

Mavor is the author of six books, all of which have been widely reviewed in the press, including the TLS, Frieze, Village Voice and the Los Angeles Times. Titles of her books include Becoming: The Photographs of Clementina, Viscountess, Hawarden (1999), Pleasures Taken: Performances of Sexuality and Loss in Victorian Photographs (1995), and Black and Blue: The Bruising Passion of Camera Lucida, La Jetée, Sans soleil and Hiroshima mon amour (2012). Mavor’s Blue Mythologies: A Study of the Colour (Reaktion, 2013, Turkish and Chinese translations, 2015) ‘coaxes us into having a less complacent attitude…even when it comes to something as apparently innocuous as a color’ (Los Angeles Review of Books). Her Reading Boyishly: Roland Barthes, J. M. Barrie, Jacques Henri Lartigue, Marcel Proust, and D. W. Winnicott was named by Turner-Prize winner Grayson Perry in The Guardian as his 2008 as 'Book of the Year.' Aurelia: Art and Literature Through the Eyes and Mouth of the Fairy Tale (Reaktion, 2017) is her most recent monograph.

Mavor received an Arts Council grant for her film FULL (2104, made with Megan Powell), which is original for its elegiac approach to a boy’s anorexia. Screenings of FULL in the UK, include The Whitworth (Manchester) with an in-conversation with Maria Balshaw (Director, Tate Modern) and at London’s Freud Museum with Susie Orbach.

Her poetry, fiction and essays have appeared in Flash Magazine, PN Review, Short Fiction and Cabinet. Frieze Masters celebrated the 500th anniversary of Thomas More’s Utopia with her reflective essay: ‘The Closed Cosmogony of Utopia’ (2016).

New work by Mavor will appear in Hotel #4.

Mavor is the author of six books, all of which have been widely reviewed in the press, including the TLS, Frieze, Village Voice and the Los Angeles Times. Titles of her books include Becoming: The Photographs of Clementina, Viscountess, Hawarden (1999), Pleasures Taken: Performances of Sexuality and Loss in Victorian Photographs (1995), and Black and Blue: The Bruising Passion of Camera Lucida, La Jetée, Sans soleil and Hiroshima mon amour (2012). Mavor’s Blue Mythologies: A Study of the Colour (Reaktion, 2013, Turkish and Chinese translations, 2015) ‘coaxes us into having a less complacent attitude…even when it comes to something as apparently innocuous as a color’ (Los Angeles Review of Books). Her Reading Boyishly: Roland Barthes, J. M. Barrie, Jacques Henri Lartigue, Marcel Proust, and D. W. Winnicott was named by Turner-Prize winner Grayson Perry in The Guardian as his 2008 as 'Book of the Year.' Aurelia: Art and Literature Through the Eyes and Mouth of the Fairy Tale (Reaktion, 2017) is her most recent monograph.

Mavor received an Arts Council grant for her film FULL (2104, made with Megan Powell), which is original for its elegiac approach to a boy’s anorexia. Screenings of FULL in the UK, include The Whitworth (Manchester) with an in-conversation with Maria Balshaw (Director, Tate Modern) and at London’s Freud Museum with Susie Orbach.

Her poetry, fiction and essays have appeared in Flash Magazine, PN Review, Short Fiction and Cabinet. Frieze Masters celebrated the 500th anniversary of Thomas More’s Utopia with her reflective essay: ‘The Closed Cosmogony of Utopia’ (2016).

New work by Mavor will appear in Hotel #4.