BEIGE Writing...

Ahmed NAJI

in conversation with Sam DIAMOND

Ahmed Naji is an Egyptian novelist and writer. His novel Using Life was published in Arabic in 2014 to widespread critical acclaim. Set in a hellish, fantastic version of Cairo, Using Life explores the city on the brink of destruction, while its young people move from party to party, having sex and taking drugs.

When the Egyptian weekly Akhbar al-Abad published a chapter of Using Life in 2014, Naji was charged with ‘indecency and disturbing public morals’ after the excerpt apparently caused a reader to have heart palpitations due to its explicit content. Naji was sentenced to two years in prison.

When the Egyptian weekly Akhbar al-Abad published a chapter of Using Life in 2014, Naji was charged with ‘indecency and disturbing public morals’ after the excerpt apparently caused a reader to have heart palpitations due to its explicit content. Naji was sentenced to two years in prison.

After his release from prison, Naji moved from Egypt to the US, where Sam Diamond talked to him about how he’s acclimatising to his new life, Saudi Arabia’s new city of the future, and what’s next for his writing.

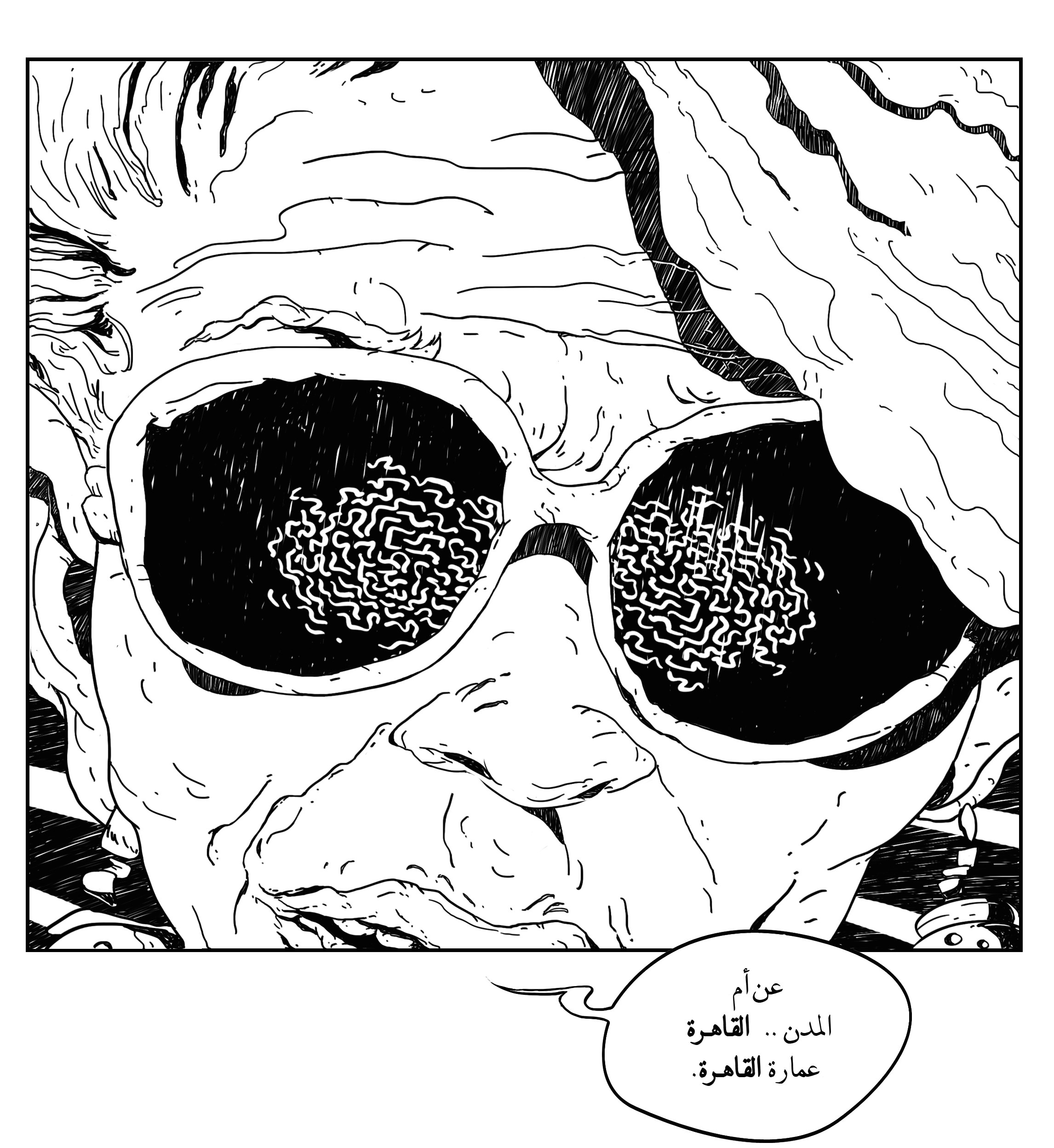

An illustration by Ayman Al-Zorkany, from Using Life (2014)

An illustration by Ayman Al-Zorkany, from Using Life (2014)I think it would be an understatement to say that the past few years have been very eventful for you. You wrote a novel, Using Life, were imprisoned for its content and then moved from Egypt to the US, where you and your wife have very recently had your first child. Could you give me a quick recap of these events from your own perspective?

Well, when I was writing the novel I didn’t ever expect to have this impact and to cause these problems. I always thought of myself as someone coming from outside mainstream culture, not the kind of writer who cared about fighting against political taboo or censorship. I just cared about the art of fiction. I was hoping to achieve something with novel, to write something that I’d enjoy writing and my friends would enjoy reading.

Suddenly, when the case happened, it was a huge shock. We didn’t expect it at all. When I was in prison I started to rethink my career as a journalist and a writer. Until then, I hadn’t thought of myself as a writer, I didn’t realise that I was totally loyal to writing and to the craft of fiction. But suddenly when I was in prison I thought: fuck it, I’m writing! I have to focus and take it seriously.

What happened had a huge impact on the the Arab cultural and literary scene, and it also had a huge impact on me. It changed my position on society and on Egyptian and Arabic culture entirely. Once when I was in the prison, one of the prison officers came to me and said: ‘Hey, Ahmed, do you have Samira’s number?’ [a character in Using Life]. I asked him what he was talking about and he told me he was joking, that he liked the novel. I froze, I didn’t understand his joke and I thanked him. After three months I saw him again. He said: ‘Wow, you're still here!?’

Well, when I was writing the novel I didn’t ever expect to have this impact and to cause these problems. I always thought of myself as someone coming from outside mainstream culture, not the kind of writer who cared about fighting against political taboo or censorship. I just cared about the art of fiction. I was hoping to achieve something with novel, to write something that I’d enjoy writing and my friends would enjoy reading.

Suddenly, when the case happened, it was a huge shock. We didn’t expect it at all. When I was in prison I started to rethink my career as a journalist and a writer. Until then, I hadn’t thought of myself as a writer, I didn’t realise that I was totally loyal to writing and to the craft of fiction. But suddenly when I was in prison I thought: fuck it, I’m writing! I have to focus and take it seriously.

What happened had a huge impact on the the Arab cultural and literary scene, and it also had a huge impact on me. It changed my position on society and on Egyptian and Arabic culture entirely. Once when I was in the prison, one of the prison officers came to me and said: ‘Hey, Ahmed, do you have Samira’s number?’ [a character in Using Life]. I asked him what he was talking about and he told me he was joking, that he liked the novel. I froze, I didn’t understand his joke and I thanked him. After three months I saw him again. He said: ‘Wow, you're still here!?’

I told him that it looked like I was going to stay there for longer. He said, ‘You know man, can you write in English?’ I told him that I couldn’t perfectly but that I could read and write simple things in English. He told me that when I got out I should stop writing in Arabic, that I should start writing English, because Arabic culture and civilisation is fucked up, people outside can’t understand what you're writing, that I should stop writing in Arabic and start writing English. And this was advice from a prison guard!

This showed me that the situation in the Arabic region was getting worse and worse, particularly with regard to freedom of expression. When I got out I found that the situation had become even more difficult. It was impossible for me to work; I stayed in Egypt for a year and a half but I wasn’t able to write or publish, because most of the newspapers and websites I’d written for were closing and were under pressure from the government. So it looked like getting out of the country and establishing a new space was the only solution.

So are you planning to start writing in English?

My English isn’t yet good enough. And now I’m in the US, my wife has a job, I have a new daughter—who’s an American citizen. I got a scholarship at a university in Las Vegas so I’m moving to Nevada where I’ll stay for three years.

But I’m facing more complicated critical questions; I don’t like the position of writer-in-exile. I don’t want to end up as an Egyptian or Arab writer living in the States who ends up writing only about Arab and Egyptian politics, although this is part of my identity. So I’m just looking to learn more, to get to know more, to be a part of the new society that I’ve chosen, which is, for now, American society.

And this has its own complications: the American cultural scene and American society in general is so built around political identity. Even before doing anything you find yourself labelled. For me, for example, last month I was doing interviews with an American journalist and at one point in the interview he asked me a question which started: ‘As a brown writer...’ I was shocked! I asked him: what is a brown writer? So you start to discover that you have labels that you don't understand. For me it was the first time I’d heard of this thing, The Brown Writer. And it took me a while to understand it. But of course I refused it, and I told him that I see myself as a beige writer, and we are beige people, and we have been discriminated against for years!

So, I’m looking forward to learning more about this society and culture and to find my own place in it. Am I going to write in English? Maybe. It’s a huge and hard journey to move from language to language, you have to build your own voice and I need more time and work to build my English. So for now I’m writing in Arabic and for now I’m depending on magnificent translators that I’ve worked with in the past, like Benjamin Koerber.

An illustration by Ayman Al-ZORKANY, from Using Life (2014)

An illustration by Ayman Al-ZORKANY, from Using Life (2014)

Have you read W.G. Sebald?

The first Arabic translations of Sebald are coming out next year, so I’m waiting for it.

He lived in England and could write in English but consciously decided to write in German and to work with an English translator.

The history of literature is full of these stories. There is Milan Kundera, who moved from the Czech Republic to France and then began to write in French, also Nabokov with Russian and English. I don’t know if I’m going to take this path or not, but I’m open to all options and I’m focused on learning and understanding.

Using Life like a melancholic novel to me. There’s a lot of joy and hedonism there but there’s also an element of conspiracy and the characters losing control against their urban environment. Do you think it prefigured the revolution in some sense?

I finished the first draft of the novel several months before the revolution. I didn’t change it at all even after the revolution, because even after what happened during the revolution it looked to me after the first couple of months as if there wouldn’t be a huge change, because Egypt is a big country that’s connected with the world system, and Egypt was impacted more by regional powers and regional authorities who looked as if they would choose either the military or the Muslim Brotherhood. In the novel, and in my writing in general, I don’t care so much about political change but more about the effect of political change on the people and on the city. The main core of the novel was my city, Cairo. What I predicted in this novel was that Cairo doesn’t have a future. And this is what has happened: they’re building a new capital in the desert.

The government plan is to go to the desert and the build a new capital, Dubai-style, and to leave Cairo. The urban problem related to the city itself will not be changed by any revolution, because it’s so related to how the Egyptian state has been structured—it’s been constructed as a central state, and in a huge country with a population of more than a hundred million people, all connected to Cairo.

The first Arabic translations of Sebald are coming out next year, so I’m waiting for it.

He lived in England and could write in English but consciously decided to write in German and to work with an English translator.

The history of literature is full of these stories. There is Milan Kundera, who moved from the Czech Republic to France and then began to write in French, also Nabokov with Russian and English. I don’t know if I’m going to take this path or not, but I’m open to all options and I’m focused on learning and understanding.

Using Life like a melancholic novel to me. There’s a lot of joy and hedonism there but there’s also an element of conspiracy and the characters losing control against their urban environment. Do you think it prefigured the revolution in some sense?

I finished the first draft of the novel several months before the revolution. I didn’t change it at all even after the revolution, because even after what happened during the revolution it looked to me after the first couple of months as if there wouldn’t be a huge change, because Egypt is a big country that’s connected with the world system, and Egypt was impacted more by regional powers and regional authorities who looked as if they would choose either the military or the Muslim Brotherhood. In the novel, and in my writing in general, I don’t care so much about political change but more about the effect of political change on the people and on the city. The main core of the novel was my city, Cairo. What I predicted in this novel was that Cairo doesn’t have a future. And this is what has happened: they’re building a new capital in the desert.

The government plan is to go to the desert and the build a new capital, Dubai-style, and to leave Cairo. The urban problem related to the city itself will not be changed by any revolution, because it’s so related to how the Egyptian state has been structured—it’s been constructed as a central state, and in a huge country with a population of more than a hundred million people, all connected to Cairo.

And this has made Cairo extremely crowded, extremely polluted. It's now impossible to rescue, it’s a version of hell, which is how I presented it in Using Life. As you say, Cairo has a central place in the novel. Do you think Cairo is unique in this way, and what’s your impression of the city now?

I don’t think the problem is unique to Cairo, it’s general to the idea of the modern city. Around the world we are seeing how the Dubai model is becoming the goal for the modern city.

If you look to China, for example, they have been building these huge, empty cities that are full of skyscrapers, tall buildings of glass and metal. Cities designed for companies, not people, where they pay low tax and get the freedom to shape urban space.

When I moved to the US I was originally in Arlington, Virginia. It was very interesting, because it’s a very open city with a lot of space, but they’ve also started to build these skyscrapers. It’s crazy, I can’t understand it: they have all this space, why not use it to build horizontally? But they choose to build in glass-and-metal. When they started doing this in Arlington all of these huge companies moved in, so the Nestlé headquarters are in Arlington, all of these international companies are moving there. Suddenly you walk through the city and you realise it hasn’t been developed to serve the people who live there but to facilitate these companies.

We are living in a world where the idea of developing the world is not linked to developing people. It’s not about improving education or healthcare. All politicians talk about is investment, development, bringing in companies and business, creating populations who only exist to serve these companies. This was part of the novel: it’s about people who are stuck between old cities and heritage and a modern idea of development.

If capital has claimed urban space, do you see art or literature as a way of taking something back or reclaiming space?

I don’t think art and literature can take anything back, but at least they might be able to create a space for people to rethink what’s happening, to discover what’s happening around them and to stay alert. For me, this is enough.

If people read my novel and were shocked at the language, experienced it as tough or rough, then maybe the second step is for them to ask themselves why I used that language: if you’re living in a city like Cairo, there’s no other language you can use to write about it. This should alert them that this language is part of the city, and that violence is being organised by the political Neoliberal agenda and so on...

I guess using rough language is the opposite of these smooth glass buildings and these clean streets that don’t have people on them.What are you working on now? What’s next for you?

I’ve finished the first draft of a new novel, which hopefully should appear next year. It started as a simple love story: a divorced woman trying to rebuild her life. This time the story doesn’t take place in Cairo, but she escapes Cairo and the revolution towards Sinai and towards the future, which is Mohammed bin Salman’s new kingdom, Neom. Do you know about Neom? I’ve seen the website...

If you haven’t been following this, Neom is a new plan by Saudi Arabia to build a new city for robots and technology. So she escapes to Neom, so most of the novel happens in this imaginary future city, which doesn't yet exist. This will be my second novel.

Also recently received a grant from The Arab Fund for Arts and Culture (AFAC) to work on a non-fiction book, which I’m calling Rotten Evidence. It’s about my time in prison and also covers the case, mostly related to diaries I wrote secretly while in prison.

So I’m writing this book about my experiences, but it’s also connected to another project: I’m planning to start a website, in Arabic but also maybe in English, to collect, document and publish other Egyptian and Arabic prisoners’ writing. I want to use this to raise awareness of their situation.

The decision to publish in both Arabic and English is of course to make it more accessible, but also because most of the prisons have actually been built and supported by European and American money. The Egyptian government doesn’t have enough money to build prisons itself, so they’ve brought in European and American companies and funding. So for example if you enter police station in Egypt, any detention room, the air conditioning is provided by the European Union; when I was in prison, the air conditioning ducts were always emblazoned with the European Union logo. So you can see how globalisation touches on everything, even in prison.

But of course my main project for the moment is being a father. How do you approach writing non-fiction as opposed to writing fiction?

Well, I worked as a journalist, that was my main source of income for years. For me, I think more about the audience and readers when I’m writing non-fiction. I focus on writing in a simple, easy way that catches the reader’s attention. I see myself as a servant of the reader.

Maybe it’s because of my journalism background, but when I’m writing fiction I don’t really care that much about the reader.

Also recently received a grant from The Arab Fund for Arts and Culture (AFAC) to work on a non-fiction book, which I’m calling Rotten Evidence. It’s about my time in prison and also covers the case, mostly related to diaries I wrote secretly while in prison.

So I’m writing this book about my experiences, but it’s also connected to another project: I’m planning to start a website, in Arabic but also maybe in English, to collect, document and publish other Egyptian and Arabic prisoners’ writing. I want to use this to raise awareness of their situation.

The decision to publish in both Arabic and English is of course to make it more accessible, but also because most of the prisons have actually been built and supported by European and American money. The Egyptian government doesn’t have enough money to build prisons itself, so they’ve brought in European and American companies and funding. So for example if you enter police station in Egypt, any detention room, the air conditioning is provided by the European Union; when I was in prison, the air conditioning ducts were always emblazoned with the European Union logo. So you can see how globalisation touches on everything, even in prison.

But of course my main project for the moment is being a father. How do you approach writing non-fiction as opposed to writing fiction?

Well, I worked as a journalist, that was my main source of income for years. For me, I think more about the audience and readers when I’m writing non-fiction. I focus on writing in a simple, easy way that catches the reader’s attention. I see myself as a servant of the reader.

Maybe it’s because of my journalism background, but when I’m writing fiction I don’t really care that much about the reader.

Using Life in its first English translation (University of Texas Press, 2017)

Using Life in its first English translation (University of Texas Press, 2017)I have a reader in mind, but it’s usually a couple of close friends I grew up with. I don’t care about being clear or informative, I feel more free to play with language, to demolish structure and then rebuild it. Maybe that’s the reason that I received all these messages from readers telling me that they used to read my articles and my journalism, ‘We loved it, but we didn't like your novel, it didn't make sense.’ They want the simple story. So when I’m writing fiction I want to stay away from that. I want to create something more complicated, something that challenges the craft of literature. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t.

If I’m writing non-fiction I want to write something that people can read on the beach or on the toilet. If I was on the beach and I found someone reading my novel I would be offended.

I read your novel on the beach...

Ha! Well I hope it worked for you.

Ahmed NAJI is an Egyptian novelist and journalist born in Mansoura in 1985. He is the author of three books, Rogers (2007), Seven Lessons Learned from Ahmed Makky (2009) and The Use of Life (2014), as well as numerous blogs and other articles. He was also a journalist for Akhbar al-Adab, a state-funded literary magazine, and frequently contributed to other newspapers and websites including Al-Modon and Al-Masry Al-Youm. He is currently based in Washington DC. Visit his website at https://ahmednaji.net/.

Sam DIAMOND is a writer, researcher and musician originally from London and now based in Berlin. He is currently finishing a PhD project on the conceptual history of authenticity in 20th Century American fiction and journalism at Queen Mary University of London. He works in technology. You can follow him on Twitter @samueldiamond.

Sam DIAMOND is a writer, researcher and musician originally from London and now based in Berlin. He is currently finishing a PhD project on the conceptual history of authenticity in 20th Century American fiction and journalism at Queen Mary University of London. He works in technology. You can follow him on Twitter @samueldiamond.