Jeffrey VALLANCE

St. Luke on a Rump Roast

Whatsoever parteth the hoof,

and is clovenfooted and cheweth the cud,

among the beasts, that shall ye eat.

—Leviticus, 11:3

and is clovenfooted and cheweth the cud,

among the beasts, that shall ye eat.

—Leviticus, 11:3

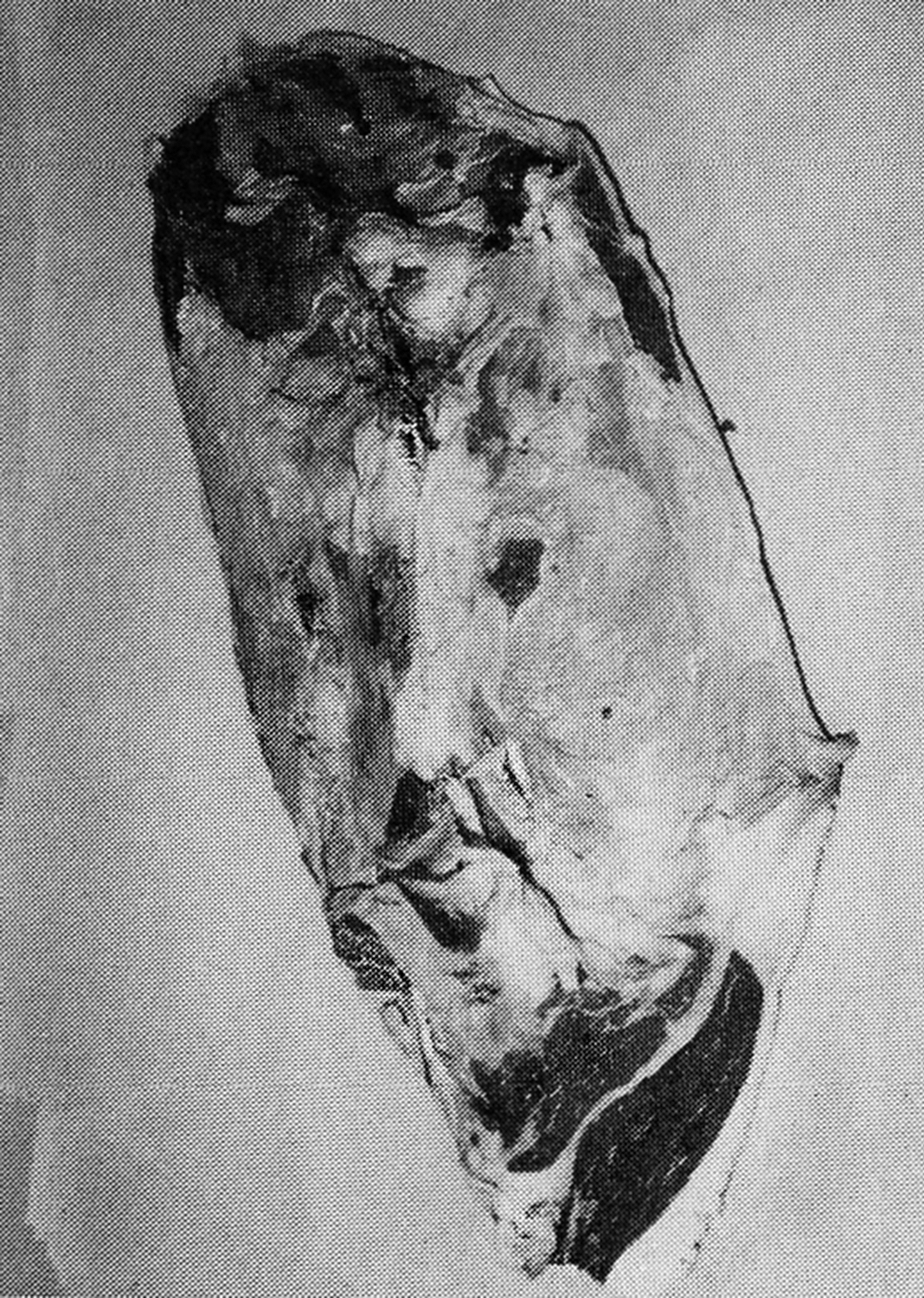

While living in Las Vegas, I discovered a spontaneous image of the evangelist St. Luke on a slab of meat cut from a beef hindquarter. This anomalous image manifested itself in a book belonging to the library at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas entitled Meat Handbook (published in 1979), by Albert Levie. This supermundane portrait of the evangelist appeared by chance in an illustration of the bottom round cut of beef.

According to Levie, “Cuts from the round are generally regarded as ‘rough cuts.’ They are marginal for broiling and oven roasting. Not as tender or clear as the top round, the bottom round is sometimes used for the roast beef by barbecue operations. The slow moist heat of a covered barbecue controls the palpability of the finished product.”

Saint Luke is the patron saint of physicians, surgeons, butchers, cattlemen, bachelors, bookbinders, brewers, hospitals, art guilds, and artists (including painters, sculptors, goldsmiths, lacemakers, and stained glass workers). St. Luke’s symbols include the Winged Ox, a calf, artist’s tools (easel, palette, and brushes), a painting of the Blessed Virgin, phials of medicine, physician's robes, and an open book of holy scriptures. On St. Luke’s Feast Day (October 18), foods served include any palatable beef recipe—and for dessert, a cake is baked in the shape of an open book decorated with winged oxen. In Oxfordshire, England, tasty raisin Banbury tarts are served at fairs which are under St. Luke’s patronage.

According to Levie, “Cuts from the round are generally regarded as ‘rough cuts.’ They are marginal for broiling and oven roasting. Not as tender or clear as the top round, the bottom round is sometimes used for the roast beef by barbecue operations. The slow moist heat of a covered barbecue controls the palpability of the finished product.”

Saint Luke is the patron saint of physicians, surgeons, butchers, cattlemen, bachelors, bookbinders, brewers, hospitals, art guilds, and artists (including painters, sculptors, goldsmiths, lacemakers, and stained glass workers). St. Luke’s symbols include the Winged Ox, a calf, artist’s tools (easel, palette, and brushes), a painting of the Blessed Virgin, phials of medicine, physician's robes, and an open book of holy scriptures. On St. Luke’s Feast Day (October 18), foods served include any palatable beef recipe—and for dessert, a cake is baked in the shape of an open book decorated with winged oxen. In Oxfordshire, England, tasty raisin Banbury tarts are served at fairs which are under St. Luke’s patronage.

Winged Calf

St. Luke was one of the four evangelists who wrote the gospels of the New Testament. Although known as the Greek Physician, St. Luke was born in Antioch, Syria. (The city of Antioch was an early Christian center where the Spear of Destiny was preserved and where Santa Claus was born.) The Christian symbol of St. Luke is the ox or winged calf. A prophetic passage in Revelation 4:6-8 describes the “behind” of the Winged Calf as “full of eyes within.” In butcher-shop terminology, the “eye of the round” is a tubular core of meat running through the entire beef hindquarter; when sliced into steaks, the omnipresent eye appears in each cut. (A perversion of this concept can be seen in the diabolical imagery of the black mass, in which worshipers kiss the devil’s posterior, often depicted as having eyes.)

In the Bible, the word “ox” denotes a bovine animal of either sex and is synonymous with the word “cattle.” Emblematic of sacrifice, the ox was often used during the time of the Old Testament for sacrificial blood offerings. In the New Testament, the Ox was present at the Holy Manger (or crèche), witnessing the birth of Christ. According to “cattle lore,” the ox in the stable at Bethlehem knelt down on its knees at the moment of the birth of the Baby Jesus (Luke 2:7). In West Devonshire, England, it is claimed that at the stroke of midnight on Christmas Eve, oxen in their stalls drop to their knees in an attitude of adoration. Traditionally, it is said that the streaming breath from the nostrils of oxen kept the Baby Jesus warm in the manger. The ox played an irrefutably seminal role in the Biblical drama, so it seems to make sense that the bovine image of St. Luke would appear on his animal totem—the ox.

Almighty Bull

In the ancient Middle East, the ox was considered an exceedingly sacred animal. The word El (as in Elohim) is the Hebrew name for the Supreme God—and also the name of a bull deity. El is worshiped as the El Shaddai (God Almighty). Some Muslim scholars liken the root of the Islamic word for God "Allah" to the word El. The emblems for El include the horns of a bull, a horned crown, and the horn-shaped crescent moon. In the Old Testament, bulls were sacrificed as burnt offerings for atonement. “You shall take of the blood of the bull, and put it on the horns of the altar with your finger; and you shall pour out all the blood at the base of the altar.” (Exodus 29:12) An animal horn represented protection and strength. A pair of cherubim (winged oxen) guarded the Holy of Holies in King Solomon’s Temple. The term cherubim signifies “to plough” as by oxen. The guardian cherubim are nearly identical to Assyrian winged bulls, having oxen bodies with human faces. (Ezekiel 1:10) In Thinking in Pictures, Temple Grandin compares modern cattle slaughterhouses with ritual slaughter in the grand Temple in Jerusalem. Grandin describes both as stairways to heaven. The Book of Numbers metaphorically portrays God (Elohim) as having “the horns of the wild ox.” (Numbers 24:8) God is represented as having the strength of a mighty bull. This may explain why, when Moses climbed up Mt. Sinai, the Israelites so hastily began worshiping a golden calf. When Moses descended the mountain, people saw that “his face was horned.” The Hebrew term karan, or “animal horn,” is used figuratively for Moses. More precisely, “horned” means “his face shone”—glorified as if by rays of light. (Exodus 34:35) In the Ten Commandments it is written, "Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image." However, at the Temple in Jerusalem, twelve oxen effigies held up a massive water basin called the Brazen Sea. Four groups of three oxen looked north, south, east, and west, with hind parts gathered inward. Priests used this massive basin, made in King Solomon’s reign, for ritual cleansing. The modern Church of Latter Day Saints uses baptismal fonts in their temples, based on the design of the Brazen Sea (complete with oxen supporting the basin), that are only used for proxy baptisms of the dead. Stylistically these oxen resemble Assyrian kirubi (winged bulls), the massive bullocks guarding large structures and gateways.

Saint of Art

Saint Luke is primarily known as the patron saint of artists, and it has been asserted since the sixth century that St. Luke was in fact a painter and sculptor. Many believe that he painted the first Madonna and Child image. The Arabian Saint John Damascene first identified Luke as painter of the revered Madonna and Child. According to chapter 27 and 28 of The Acts of the Apostles, St. Luke and St. Paul were shipwrecked on Malta for three months. It is believed that at this time St. Luke made a cave painting, Our Lady of Mellieha, which has been found in a recess in the back of a large cave on the island. The sacred picture is still venerated and held in great esteem, although a considerable portion of the image has flaked away due to the natural environment of the grotto. To add insult to injury, red paint has been smeared for some inexplicable reason into the flaked-off area of the painting. Nevertheless, one can still make out the rather primitive depiction of the Blessed Virgin, her head covered by a blue veil dotted with faded golden stars. A beautiful halo hovers over her and the Christ Child, who clutched the Virgin’s right arm. Furthermore, innumerable supernatural phenomena have been connected with the veneration of this sacred image, including the miraculous cessation of plagues and droughts.

A 3-D Saint

There is also a sculpture associated with St. Luke, a wood carving of a Madonna and Child known as Our Lady of Atocha preserved in the Basilica of Atocha in Spain. The figure, carved out of a single block of wood, represents a seated Madonna with the Christ Child on her knee, holding in her hand the apple of Adam and Eve. According to tradition, the wooden figure was carved by Nicodemus (it was Nicodemus, along with Joseph of Arimathaea, who together wrapped the body of Christ in the Holy Shroud) and only painted by St. Luke. The apostle then handed over the sculpture to the disciples of St. Peter, who carried it to Spain.

Since the time when St. Luke painted Our Lady of Atocha, several other versions of the image have been made that closely resemble the original, but with a “detachable” Christ Child. When the Baby Jesus is removed from the main statue, He is then known as the Little Pilgrim of Atocha. One version of the Little Pilgrim was brought to Mexico by Spanish missionaries, and the Pilgrim now wears what looks like a Mexican sombrero. Devotion to the Little Pilgrim spread to the United State in 1831 when another version of the statuette was brought to a cattle ranch known as Potrero de Chimayo, located thirty miles north of Santa Fe, New Mexico. One can imagine cowboys in the Southwest gathered around the campfire singing the old roundup song “Git Along Little Doggie.”

In folklore, it is claimed that a mysterious apparition of a child of unearthly beauty, bearing an endlessly replenishing jug of water and basket of bread, often visits prisoners in jail, miners deep in the bowels of the earth, and soldiers in POW camps. It is believed that the statue of the Little Pilgrim itself “comes to life” to make these pilgrimages, and evidence of this can be observed by viewing soiled and worn out sandals on the statue of Chimayo.

Artist Guilds

The Guild of Saint Luke (Sint Lucasgilde), founded in Antwerp in 1382, is named in honor of the Evangelist Luke, the patron saint of artists. In Antwerp, guild membership was required for an artist to take on apprentices or sell paintings to the public. The Guild of Saint Luke not only represented painters and sculptors, but also art dealers, amateurs, and even art lovers (liefhebbers). Guild members could sell their works at the guild-owned showrooms, including a market stall in front of the Cathedral of Our Lady in Antwerp. Like a court of law, the guild made judgments on disputes between artists and other artists or their clients. The guild sponsors a special chapel decorated with an altarpiece of their patron saint.

A group of artists dedicated to elevating themselves above mere craftspeople founded Rome’s Academy of Saint Luke (Accademia di San Luca) in 1593. They named the Academy after Saint Luke, since, according to legend, he painted the first portrait of the Virgin. In 1605, Pope Paul V granted the Academy the right to pardon a condemned criminal on the Feast of St. Luke. In 1620, Pope Urban VIII extended its rights to determine who was considered an “artist.” (This is still practiced by various groups.) The institution was also given the authority to tax all artists and art dealers. On October 18, 1572, El Greco paid his dues to Rome’s Academy of Saint Luke (Oct. 18 is the celebratory Feast of St. Luke). The Academy is still active today and encourages artists to donate a work of art (especially a portrait) to their collection. They have acquired an exceptional collection of paintings and sculptures, including about 500 portraits, along with a fine collection of drawings. Rather than perpetuating the medieval nature of the guild system, they now function more like an art institute. They’ve ceded much power to others.

The Art of Flesh

The beefy face of St. Luke that turned up on the piece of flesh cut from a bullock’s buttocks most closely resembles a painting of St. Luke by Domenikos Theotokopoulos (more popularly known as El Greco). As the Spanish painter was born in 1541 on the island of Crete, however, he should more properly be called El Creta. (Crete is the land of the Minotaur, the mythological bull.)

In 1566, El Greco moved to Venice, a city that not only boasted that her painters had “perfected the art of a flesh,” but also houses the exhumed bodily remains of St. Luke enshrined in the Basilica of Santa Giustina. (The relics of the saint are kept in a tomb in a side chapel of the Basilica that is decorated in blue stone with golden panels depicting the life of the saint.) In 1577, El Greco moved to Toledo, the headquarters of the Spanish Inquisition, and it is there in the Toledo Cathedral that his portrait of St. Luke is enshrined.

Victoria Reynolds, Saint Luke in the Round, 1996

& El Greco, San Lucas Evangelista, c. 1602–1605

(detail)

(detail)

When I was first trying to find a representation that was similar to the meat image, I instinctively grabbed a book on El Greco, first turning to his painting Burial of Count Orgaz, which depicts an orgasmic hoard of bearded heads looking this way and that, all shrouded in an explosion of vaginal drapery. But then turning the page was like hitting a Vegas jackpot, because there, looking up at me, was El Greco’s astonishing portrait Saint Luke! This portrait (circa 1604) has many of the same features as the meat simulacrum. Both portraits depict the saint in three-quarter view, turned slightly to the right, and both have the unmistakable Van Dyke beard, an irregular receding hairline, a prominent Greek nose, and a pronounced shirt-collar. Paintings of Saint Luke are frequently self-portraits with the artist depicted as the Evangelist. (Many art historians believe that El Greco’s portrait of St. Luke may actually be a self-portrait.) In 17thcentury Antwerp, the Guild of St. Luke produced many paintings of meat and slaughtered animals. A contemporary meat painting by Victoria Reynolds, St. Luke in the Round, depicts the pareidolic image of St. Luke found on a rump roast.

Grecian Formula

There are several correlations between St. Luke and El Greco. Both men were nicknamed “The Greek,” and both were artists who painted religious subject matter. Each has been associated with a Mediterranean island (Malta for the saint and Crete for El Greco), and El Greco studied the art of painting flesh in Venice, where St. Luke’s disinterred flesh is maintained. Finally, the head of St. Luke, appeared on the body of a bull in the Meat Handbook, it’s flesh intended for human consumption, while the artist El Greco was born on the isle of the Minotaur, the mythic beast with the head of a bull and the body of a man who consumes human flesh.

Holy Cattle

The bovine connection to St. Luke is an intriguing one. The Saint’s evangelical symbol is the calf, and his miraculous image, like a decapitated head, appeared on a hunk of beef. Sacred animals in the Old Testament, cattle were often ritually slain on holy altars. In modern times, cattle are systematically butchered for the dinner table. The cow is a sacred animal in many religions such as Hinduism, which is world famous for its “sacred cows.” The ancient Egyptians worshipped a divine cow goddess named Hathor, while the Israelites, wandering in the desert, sinned and worshipped the Golden Calf. In the desert of Las Vegas (on Sahara Boulevard) one can find both the Holy Cow Casino, a Wisconsin-themed gambling hall, and the Golden Steer, a steakhouse and local watering hole. (The Golden Steer features in a painting by Norman Rockwell of cowboy actor Walter Brennan, famous for his role in the hit TV series The Real McCoys, a program coincidentally about backwards farmers living in the San Fernando Valley.)

St. Luke is associated with a statue that eventually ended up on a cattle ranch in Santa Fe. In Rome, St. Luke’s decapitated head is enshrined inside a golden reliquary decorated by an apocalyptic winged calf. The word “decapitate” comes from the root word “capital,” originally meaning “head,” and from that source we have the word “chattel” or capital property, hence the word “cattle,” which are considered valuable property. So to ask a rancher “Hey pardner, how many head of cattle do ya have yonder?” is redundant.

It seems fitting to end with the immortal words of our Lord written by the great evangelist himself, as He considered the condition of human existence here on earth: “Life is more than meat.” (Luke, 12:23)

Jeffrey Vallance

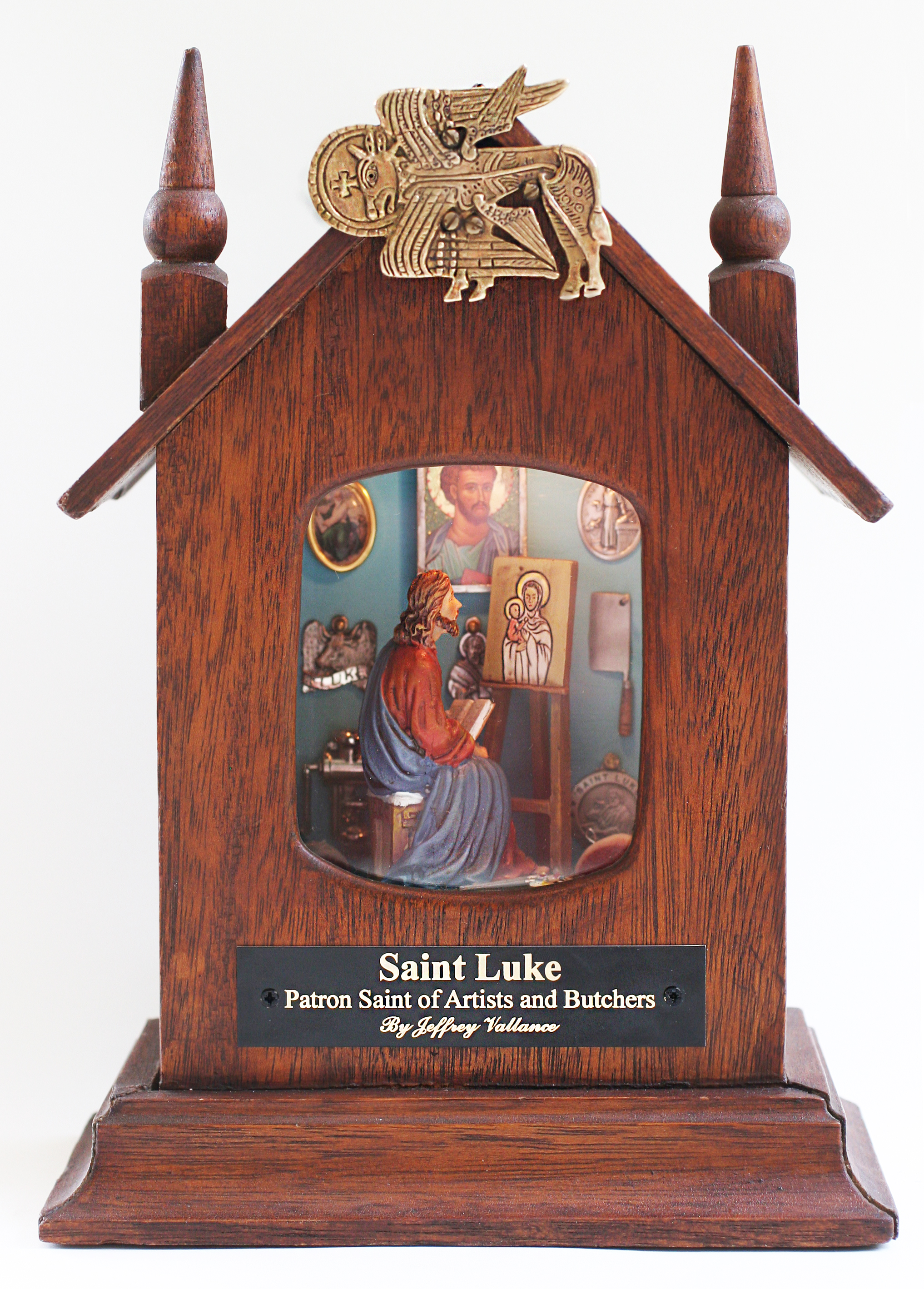

Saint Luke Reliquary, 2020

Found objects in wooden box

Jeffrey Vallance

Saint Luke Reliquary, 2020

Found objects in wooden boxwith electric light

10 x 7 ¼ x 4 ½

Evangelical Rump Roast

1 four-pound boneless beef round rump roast

¼ teaspoon dried marjoram, crushed

¼ teaspoon dried thyme, crushed 12 medium potatoes, peeled and halved

6 medium carrots, cut up

1 can peas

1 can peeled tomatoes

1 teaspoon instant beef bouillon granules

Preheat oven to 325-degrees. Meat should be at room temperature (70-degrees). Place meat, fat side up, on rack in roasting pan. Combine marjoram, thyme, dash of salt, dash of pepper; rub into meat. Roast 2¼ hours. About 45 minutes before roast is done, add vegetables and boullion to drippings around roast, turning to coat. When done, transfer meat and vegetables to a serving platter; keep warm. Serves 12.

¼ teaspoon dried marjoram, crushed

¼ teaspoon dried thyme, crushed 12 medium potatoes, peeled and halved

6 medium carrots, cut up

1 can peas

1 can peeled tomatoes

1 teaspoon instant beef bouillon granules

Preheat oven to 325-degrees. Meat should be at room temperature (70-degrees). Place meat, fat side up, on rack in roasting pan. Combine marjoram, thyme, dash of salt, dash of pepper; rub into meat. Roast 2¼ hours. About 45 minutes before roast is done, add vegetables and boullion to drippings around roast, turning to coat. When done, transfer meat and vegetables to a serving platter; keep warm. Serves 12.

This heavenly dish is especially good for celebration on the festival of St. Luke’s Feast Day, October 18.

* A previous version of this essay appeared in issue #43 of Art Issues magazine in 1996.

Jeffrey VALLANCE was born in 1955 in Redondo Beach, CA. In 1979, he received a B.A. from CSUN and in 1981 an M.F.A. from Otis. He lives and works in Los Angeles. His work blurs the lines between object making, installation, performance, curating and writing. Often his projects are site-specific such as burying a frozen chicken at a pet cemetery; traveling to Polynesia to research the myth of Tiki; having audiences with the king of Tonga, the queen and president of Palau and the presidents of Iceland; creating a Richard Nixon Museum; traveling to the Vatican to study Christian relics; installing an exhibit aboard a tugboat in Sweden; curating shows in the fabulous museums of Las Vegas, such as the Liberace and Clown Museum. In Lapland Vallance constructed a shamanic “magic drum,” In Orange County, Mr. Vallance curated the only art world exhibition of the Painter of Light entitled “Thomas Kinkade: Heaven on Earth.” In 1983, he was host of MTV’s The Cutting Edge and appeared on NBC’s Late Night with David Letterman. In 2004, Vallance received the prestigious John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation award. In addition to exhibiting his artwork, Mr. Vallance has written for such publications and journals as Art issues, Artforum, L.A. Weekly, Juxtapoz, Frieze and Fortean Times. He has published over 10 books including: Blinky the Friendly Hen, The World of Jeffrey Vallance: Collected Writings 1978-1994, Christian Dinosaur, Art on the Rocks, Preserving America’s Cultural Heritage, Thomas Kinkade: Heaven on Earth, My Life with Dick, Relics and Reliquaries, The Vallance Bible and Rudis Tractus (Rough Drawing).