BAD SCIENCE

Jason SHULMAN

talks to Dominic JAECKLE

Deep Throat (Gerard Damiano, 1972)

In the winter months of 2017, Hotel’s Dominic JAECKLE met artist Jason SHULMAN in his London studio to discuss his ongoing project, Photographs of Films, a growing series of durational photographs of canonical pieces of popular cinema. Capturing a film in its entirety—setting the exposure rate to the film’s duration—in each of these images each motion picture becomes an abstract hue of shifting colours and vague shapes. We’re left with a more atmospheric picture of the film’s feeling rather than its content as colours bleed and blur between frames and slowly recompose the film as something altogether more painterly in tone and character.

Ahead of our conversation, looking for critical precedence, the introductory remarks to Alexander KLUGE’s Cinema Stories felt appropriate. In his short piece ‘The Three Machines that Make Up Cinema,’ Kluge reflects on the technological legacy of the medium. With the dictaphone rolling, Kluge was left open on Shulman’s desk and—between drinks—remained broadly undiscussed. However, there was definitely something there in the shift of interests between technology, the idea of audience, and our want for association, implication and escapism as viewers present in Kluge’s writing as we talked through the content and contexts of Shulman’s photographs of films. Shulman would tell me I was pushing my thinking a little far, but the terms of interest were all there in our want to project meaning onto these motion pictures.

Ahead of our conversation, looking for critical precedence, the introductory remarks to Alexander KLUGE’s Cinema Stories felt appropriate. In his short piece ‘The Three Machines that Make Up Cinema,’ Kluge reflects on the technological legacy of the medium. With the dictaphone rolling, Kluge was left open on Shulman’s desk and—between drinks—remained broadly undiscussed. However, there was definitely something there in the shift of interests between technology, the idea of audience, and our want for association, implication and escapism as viewers present in Kluge’s writing as we talked through the content and contexts of Shulman’s photographs of films. Shulman would tell me I was pushing my thinking a little far, but the terms of interest were all there in our want to project meaning onto these motion pictures.

Machine Number I

APPARATUS

The photographic apparatus invented at almost the same time by the Lumière brothers in Europe and the entrepreneur Edison in the USA was both a camera and a projector. The device combined the “principle of the sewing machine” (a light-sensitive strip perforated evenly along both sides can be moved forwards by pilot pins engaging those perforation holes) with the principle of the bicycle (a crank is responsible for forward movement). All the rest is the technology of photography: lens systems, apertures, negatives, positives. This is machine number 1.

Machine Number II

THE PAYING PUBLIC

Unlike the scientist Muybridge, creator of the first moving images, the entrepreneurs Lumière and Edison from the outset had one eye on the commercial potential of film: a paying public. This machine wasn’t new. It consisted of an entrance (portal), a box-office where the money is paid, an exit, an auditorium (as in a theatre), and a public. This had always been the principle of opera, theatre, fairs, collections of curios, panoramas, world exhibitions, and the circus. Establishing this second machine ran into problems. Ten years after the invention of the camera, a “cinema of the public sphere” still had not been created.

Machine Number III

PENNY ARCADES

It was the third machine, invented in the eastern United States, that provided the “breakthrough to cinema.” This was the penny arcade. It wasn’t invented by entrepreneurs, but developed spontaneously, and by chance, in response to a demand from passersby who felt lost in New York and couldn’t afford to spend more than a cent. Their desire to escape from real life at least for a short while - to look through a peephole at a foreign world - encouraged the setting up of a series of slot machines in which strips of film could be played. These apparatuses had already done good business as an attraction at Coney Island and were now to be used again, on the sidewalk, before being stowed in stores. A peep cost one cent. The automatic machines stood side-by-side along the thoroughfares as people returned home from work. The one-cent coins spent to satisfy the desires of “city dwellers” amounted to a spectacular commercial success that the entrepreneurs had not expected. Other businessmen learned from this spontaneous outbreak of a special demand.

Some of these unerring observers later became the tycoons of commercial film. They increased the business by setting up small rooms for presentations, similar to the repair shops and clothing stores squeezed in between houses and alleyways: cinemas in which twelve or sixteen people could stand together. Abandoning the slot machines, they switched to screenings with projectors. This became an alternative to the variety shows and vaudevilles, which were expensive and required a theatre, something which could be established everywhere in the city. The “entertainment shops for film could be fit almost anywhere.” Cinema was learned at the box office of the “cinema shops.”

How does your relationship with technology inform this work?

To go back to what you were saying about requests for transposing home movies in this way, do you feel it’s important to the atmosphere of the project to keep working with popular cinema as a medium? Materials existing in the public domain?

No, no; I’ve also shot a lot of other subjects—sports, cartoons, advertisements and so on. Ages ago I collected all the footage of 9/11 from various television networks—Fox, BBC, CBS, ABC—and photographed the coverage from eight to ten o’clock or so, from when the first plane hit until the second tower fell. I wondered if I photographed all of the separate broadcasts might there be a single image amongst them, because of their editorial interpretations, that would represent or echo the time that I remember watching the event unfold live on TV? In the end I felt that no decisive picture emerged, but this [shows on laptop] was the best of them.

So, is it the duration that you’re interested in? Almost more than the subject matter?

Not particularly, but if we’re talking news footage here there are probably some seminal snippets that are too brief to work using this process. The film of the suffragette who threw herself under the horse at Epsom, I don’t think that would show any kind of interesting arc as a still. I have shot the very short Zapruder footage, the Kennedy assassination, the 8mm. I wanted to see how this culturally familiar section of a home movie would look compressed into a smear.

It does feel to me as though there is something so keenly dedicated to an analysis of the simple act of looking into the images though, no? Like an effort to map out the shape and sentience of an attention span.... A portrayal of the act of looking….

In the fuzzier ones I’ve noticed that people tend to see the things in them that they want to see, especially if it’s a familiar film. It’s apophenia. They find shapes and scenes that tally with their recollection of the film. Take the photograph of The Wizard of Oz. Sometimes someone will tell me that they can make out the shape of the Tin Man. But they don’t see the Tin Man. They’ve managed to make themselves see the Tin Man, they want to see the Tin Man.

It’s almost as if the picture works like a Technicolor Rorschach blot.

They would like him to be there so there he is.

The Wizard of Oz (Victor Fleming, 1939)

This is for why I wanted to leave Kluge on the table; I felt like he’s trying to push us into thinking more about projection. Light as a riff on understanding, you know? These films are taken, they’re already aesthetic objects, but then here they’re aestheticized again—aestheticized to a level of abstraction—and it’s up to us to project our own wants onto the image. We’ll find what we want to find. The Tin Man. It’s a yellow brick road psychology.

Yes, but this is why I was so interested in the potential ramifications of running a home movie through this process. There’s something loud going on in-between the clash of public and private matter here. Let’s say, hypothetically, I ask you to shoot my sister’s sixth birthday; I’m already telling you what I want to find when I look at the image. I’m wanting to figure my nostalgia, my relationship, the specifics of my memory through the image. However, dealing with material in the public domain—dealing with popular cinema— shifts the intonation of that desire a little. With these films, we’re encouraged to read these things from the top down and are aware that the symbolism and narrative not only points outwards in a myriad of different directions but is, largely, outside of our control.

Yes. I think there’s something in the manipulation of time that’s unique to these pictures because they differ from time lapse photographs which are always of a single event. Your sister’s sixth birthday doubtless has selective cuts from opening gifts to blowing out candles and that’s not dissimilar to a mainstream film with its script and all the different things that need to be explained. Both narratives jump around in time and this makes for a very different composition from say the classic static long exposure photograph of stars drawing curves in the sky.

Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom [Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1975]

The Passenger [Michelangelo Antonioni, 1975]

2001: A Space Odyssey [Stanley Kubrick, 1968]

For sure. But going back to Sugimoto, his pictures end up prefiguring the auditorium rather than the details of the film’s presentation. The cinema as a space is highlighted and the film erased. That’s our endpoint with his work. With your work, conversely, all we have is the screen. The cinema—the method of delivery—disappears. Do you think that in taking the flat screen, hanging it in a gallery, and voiding the original contexts of the film’s consumption, do you think you’re wanting to draw attention to our own self-acknowledgment as readers, focusing more on our own private experience of the work rather than the authority it is granted by its hanging in a gallery or screening in a cinema, as its site for argument? Are we looking at the ways in which our own treatment of material changes the material itself?

I mean, if you hang a painting in a gallery, you’re charging people to think about a given thing, approach it in a very particular kind of way...

Maybe that’s what I was trying to talk through before, that there’s a strange kind of disparity at work here. As a series, the images almost paint a picture of moviegoing as an escapist activity that is, perhaps, ultimately disposable? It feels cynical. Sceptical. We’ll hang on to an individual detail, as that’s all there will be thereafter. There’s something so curious in flattening out of the films in this way—a prefiguring of this sense of forgetfulness.

Yeah?

Yes. Bad Science. Self-supporting post-justification. You know what I mean?—This wine is off; let me grab another bottle.

Bad wine over bad science...

What I mean is that most artists behave like bad scientists. There’s a nervous tendency to reappraise and find or forge “evidence” or “meaning” after the fact. I’m trying my best not to do it with these...

I spend all my time as a bad scientist. Thinking about the art of post-justification. But it’s something so central to this series, perhaps; it really feels like they maintain such a sceptical relationship with this bad science?

Yeah. I never can be sure about the fixed meaning of these things. We’re all so prone to a change of heart.

The charm of forgetfulness. We’re invited to forget the source material, and then reapply it in terms of our own relationship with cinema.

It’s simple subjectivity. But then something else happens when they’re exhibited. Suddenly it’s about what should hang next to what?

For sure, and this takes us back to the issue of context again, to the gallery context...

Yes. At this point the selection and order becomes showmanship.

Pure showmanship. But in cooking the adjacencies between these films, you’re working curatorially rather than artistically. Hanging these things alongside each other there is an aesthetic mirroring going on, and I see your choices. But then something else happens when I come along and I can’t help but dwell on my own rendition of the relationship between Dr. Strangelove and The Agony and the Ecstasy. I’m suddenly thinking about my own relationship with form rather than your relationship with technology. It’s like a critical austerity that calls for the private ownership of a reading….

Right.

So, to my mind, these works are dedicated entirely to a scrutiny of that. This bad science. The predominance of bad science.

I couldn’t agree more. Look at these—the Italian Series—one of these pictures presented a surprising addendum to this process, I’m still unsure if it ticks the bad science box or not.

Yes. Bad Science. Self-supporting post-justification. You know what I mean?—This wine is off; let me grab another bottle.

Bad wine over bad science...

What I mean is that most artists behave like bad scientists. There’s a nervous tendency to reappraise and find or forge “evidence” or “meaning” after the fact. I’m trying my best not to do it with these...

I spend all my time as a bad scientist. Thinking about the art of post-justification. But it’s something so central to this series, perhaps; it really feels like they maintain such a sceptical relationship with this bad science?

Yeah. I never can be sure about the fixed meaning of these things. We’re all so prone to a change of heart.

The charm of forgetfulness. We’re invited to forget the source material, and then reapply it in terms of our own relationship with cinema.

It’s simple subjectivity. But then something else happens when they’re exhibited. Suddenly it’s about what should hang next to what?

For sure, and this takes us back to the issue of context again, to the gallery context...

Yes. At this point the selection and order becomes showmanship.

Pure showmanship. But in cooking the adjacencies between these films, you’re working curatorially rather than artistically. Hanging these things alongside each other there is an aesthetic mirroring going on, and I see your choices. But then something else happens when I come along and I can’t help but dwell on my own rendition of the relationship between Dr. Strangelove and The Agony and the Ecstasy. I’m suddenly thinking about my own relationship with form rather than your relationship with technology. It’s like a critical austerity that calls for the private ownership of a reading….

Right.

So, to my mind, these works are dedicated entirely to a scrutiny of that. This bad science. The predominance of bad science.

I couldn’t agree more. Look at these—the Italian Series—one of these pictures presented a surprising addendum to this process, I’m still unsure if it ticks the bad science box or not.

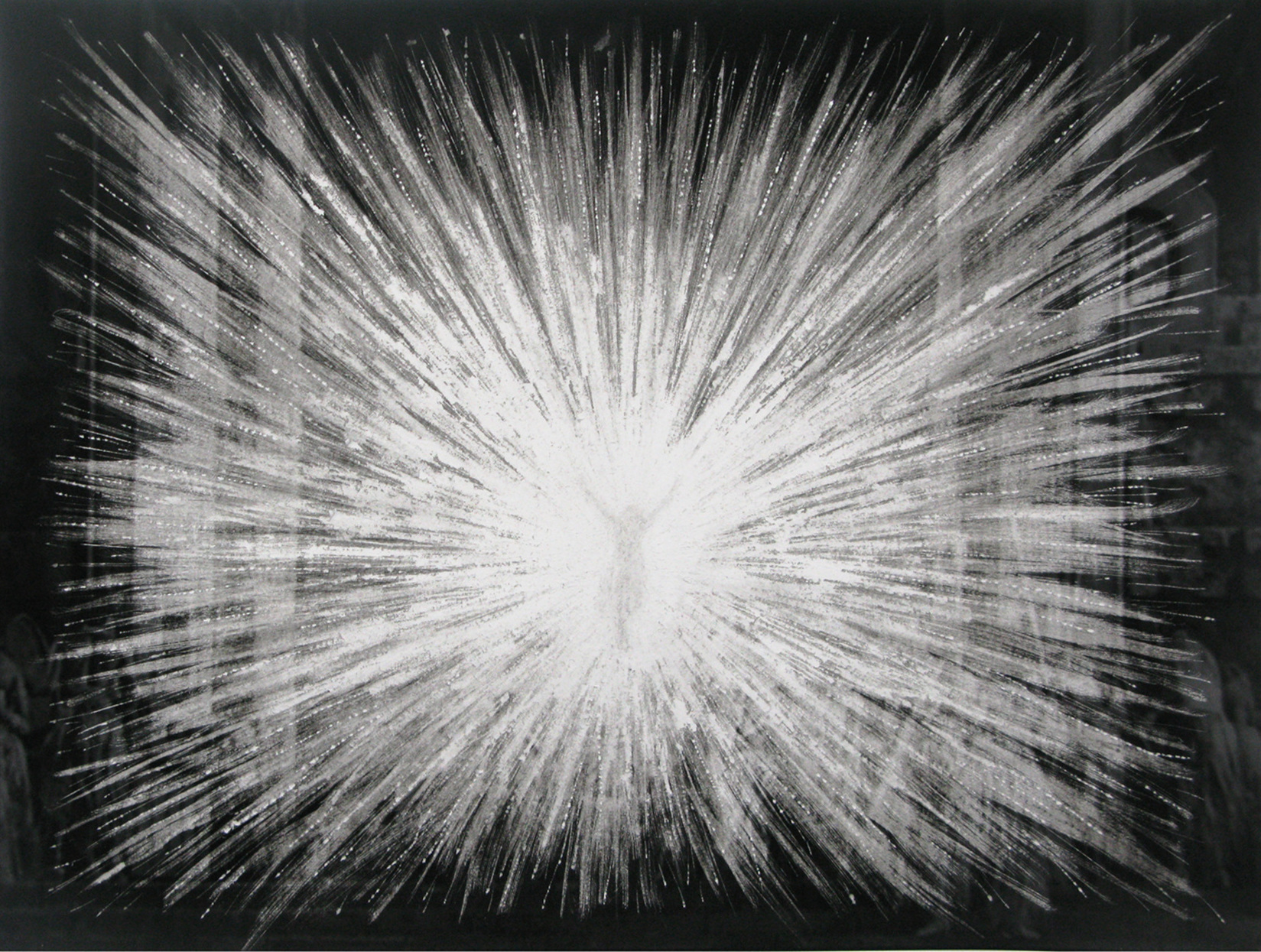

Shulman opens a book that sits on his desk, detailing a run of Italian films he shot for an exhibition in Rome earlier this year. Flicking through the pages, we pause on his photograph of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s ‘The Gospel According to St. Matthew’

This one. Look. This one’s a bloody miracle. It’s the photograph of The Gospel According to St Matthew. Check out the undeniably Turin-Shroudy representation of Jesus in the middle.

The face of Jesus.

Exactly.

I can’t imagine how that must have felt seeing that come through.

![]()

The Gospel According to St Matthew (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1972)

The face of Jesus.

Exactly.

I can’t imagine how that must have felt seeing that come through.

The Gospel According to St Matthew (Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1972)

When I re-watched the film later, I realized that the Jesus face comes from Pasolini’s directorial style. He places most of his actors’ heads in the same central field, all framed exactly the same way: big face, eyes straight at you and when they’re all added together—Behold, the son of man...

Few others are so explicit though, no?

Yeah, none apart from the Jesus one.

Sure.

And it raises the point that you could make a film that contains a hidden picture. Maybe a political film that appears innocent enough, but when translated into a single image, the audience could have been watching someone fucking a pig for two hours and never have known...A coded propaganda.

Exactly.

Everyone’s disgusted and they don’t know why.

It would work in its gestalt.

Yes.

A despot fucking a pig. Kim Jong-un? The Donald? I’m not serious, of course; it would be very tricky to make. Getting all those different accents of light required to make up the final image hidden inside the film would be a nightmare.

But to stay with the gestalt, and think about your own history as a sculptor, I’m now thinking about control. You’re relinquishing quite a lot of control, no? You can decide what to show me and what not to show me....

Yes. And I often feel like a gimp to this process. I’m just an editor or a secretary who works for the pictures…

Yeah. The level of remote control is fascinating. Say, I enter a room—see a plinth—and on the plinth is an object. That dictates the atmosphere of the room so aggressively. But these photographs of films, their innate qualities....

It’s something else entirely.

Yes.

Wild Strawberries (Ingmar Bergman, 1957)

Dr. Strangelove or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (Stanley Kubrick, 1964)

Dumbo [Samuel Armstrong, 1941]

I think cinema may be a logical extension of my other work. And maybe all my sculptural tropes are a bit cinematic since they often contain movement or an illusion of movement. As a kid, I collected 8mm films, now it’s 16mm ones that I screen every now and again. I've always been in with it. Ratcheted film.

Yes—and the cinematic toolbox is an interesting idea. I’m thinking now about ready-mades, or going back to Duchamp’s ideas; here, it’s not about repurposing found material but working with material that’s already been found. We’re stuck in this power play.... It’s all about ownership, about possession. The dynamic between discovery and the purpose of things….

Yes; and do you feel like you’re trying to charge the reader, the viewer, as some-kind-of-conceptualist? On a par with an artist? We have the two avenues at play here, no? Either we find what we’re looking for, or we have the face of Jesus staring straight out at us and determining our interactions with the image. Where possession begins, and where it ends. It really rigs our relationship with beauty, do you think? That concept?

Perhaps. But I don’t think of myself as conceptual—not in any way. I’d say that I work with my gut over concepts any day.

Yes, but there’s the inescapable precedent to the film works...

Yes.

A conceptual one.

No.

But it’s in the films themselves. I walk into the studio today and you’re shooting Silence of the Lambs and I’m thinking about all of the different implications of that film; about gender, about violence, about sexuality, about psychosis....

That’s interesting, but about you. For my part, I have to play a waiting game with the camera and see how the picture looks when it’s cooked before deciding anything. Will it show me what I’m looking for even though I don’t really know what that is until I see it. This is what I was trying to preface when I talked about the simple curiosity that underpins this work. I’m hunting for something that I can’t explain. It’s just—subjective, and I like that sense of unpredictable expectation. I mean, look at these… These pictures are a part of a long study that I’ve made of the Martini glass. I used to drink a lot of Martinis. And I wondered if there was any personal or somehow insightful work that could be gleaned from this least-prepossessing of objects with which I’ve spent so much time. At some point I started thinking about the 1933 version of King Kong, an old favourite of mine, and the relationship between Kong and Ann Darrow, played by Fay Wray. I realised that I could view Kong as a potential alcoholic. Why potential? Because he doesn’t become an alcoholic until he is beguiled by this modern lemon-haired, silver-dressed beauty who rocks up one day on Skull Island. The moment he sets eyes on her, that’s it. He’s addicted. Wray is the drink he’s been waiting for. For much of the film, the first half at least, she’s strung up—her arms in a “V” over her head—she’s literally pulling the shape of a Martini glass. In the second half, she’s in his hand. Pondered and pawed like a delicious drink awaiting consumption. So now I could connect these two themes. My goofy glass and an interpretation of the film. So the way I addressed this combination was by scraping and scarifying the prints that I’d made—dark prints—so that scratching away at the paper made Fay become a blinding yet seductive ray—or rather Wray—of light.

Yes; the Martini glass as chalice, as holy grail. As a figure of cultural fascination. But it has this use-value... This contingency. Left on its own, a Martini glass is useless.

Yes, and ugly.

Yes. But these images look almost Blakean…

Ann Darrow, V

Ann Darrow, IV

Exactly. And I don’t know if that’s a good or a bad thing but I spotted it as soon as I started hacking away at the prints. When you make something there’s always this bridge between the subject matter, technical skills and known points of reference, so the Blakean style was possibly subliminal, but maybe accidental. Fundamentally these pieces are about my relationship with Kong and with the Martini... It’s a kind of self-portrait wrung through a mangle of connections.

Yeah, and it’s whether you want to consider the thing an association or a departure; it’s always a two-way-street. It’s up to us, I guess, to decide which is the good and which the bad.

It is. But when we’re talking about the relation between these images and their relationship to their source material, their invitation for our projection on top of them, to look backwards, look downwards to their origin moment doesn’t take you as far as it does when we think about this strange invitation for use...

This is hardly new though. What we are touching on is the strange problem of the relationship of biography to truth. And it is especially problematic if what we are talking about is the biography of a film. Who is fixing the image here? The director? The editor? The lighting guy? Me? We will never know who affects the stain.

And in the end, that’s all I can show you...

A retinal stain.

Jason SHULMAN is is a sculptor whose work extends into photography, film, and painting. Analgesia, loss and the delusions inherent in perception are some of Shulman’s areas of enquiry. He often combines scientific experimentation with more formal trajectories, using optics and other basic science to expose the falsehoods that underpin our experience of reality. All images appear courtesy of the artist. Shulman is represented by Cob Gallery, London; see here for more details.

This interview also appeared in Hotel #4.

Introductory excerpts are from Alexander Kluge’s Cinema Stories, © 2007.

Translation copyright © 2007 by Martin Brady and Helen Hughs.

Use by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp.